“Yes, Sire.”

“You took it under a false name. It was put on your head but you knew your lowborn head did not deserve it.”

“Yes, Sire.”

“The boy whose name you took, Edward of Warwick, is loyal to me, recognizing me as his king. As does everyone in England.”

The child has lost his voice; only I am close enough to hear a little sob.

“What d’you say?” Henry shouts at him.

“Yes, Sire,” the child quavers.

“So it meant nothing. You are not a crowned king?”

Obviously, the child is not a crowned king. He is a lost little boy in a dangerous world. I nip my lower lip to stop myself from crying. I step forwards and I gently put my hand in Henry’s arm. But nothing will restrain him.

“You took the holy oil on your breast but you are not a king, nor did you have any right to the oil, the sacred oil.”

“Sorry,” comes a little gulp from the child.

“And then you marched into my country, at the head of an army of paid men and wicked rebels, and were completely, utterly defeated by the power of my army and the will of God!”

At the mention of God, My Lady the King’s Mother steps forwards a little, as if she too wants to scold the child. But he stays kneeling, his head sinks lower, he almost has his forehead on the rushes on the floor. He has nothing to say to either power or God.

“What shall I do with you?” Henry asks rhetorically. At the startled look on the faces of the court, I realize that they have suddenly understood, like me, that this is a hanging matter. It is a matter for hanging, drawing, and quartering. If Henry hands this child over to the judge, then he will be hanged by his neck until he is faint with pain, then the executioner will cut him down, slide a knife from his little genitals to his breastbone, pull out his heart, his lungs, and his belly, set light to them before his goggling eyes, and then cut off his legs and his arms, one by one.

I press Henry’s arm. “Please,” I whisper. “Mercy.”

I meet Maggie’s aghast gaze and see that she too has realized that Henry may take this tableau through to a deathly conclusion. Unless we play another scene altogether. Maggie knows that I can perform one great piece of theater and that I may have to do this. As the wife of the king, I can kneel to him publicly and ask for clemency for a criminal. Maggie will come forwards and take off my hood, and my hair will tumble down around my shoulders, and then she will kneel, all my ladies will kneel behind me.

We in the House of York have never done such a thing, as my father liked to deal out punishment or mercy on his own account, having no time for the theater of cruelty. We in the House of York never had to intercede for a little boy against a vindictive king. They did it in the House of Lancaster: Margaret of Anjou on her knees for misled commoners before her sainted husband. It is a royal tradition, it is a recognized ceremony. I may have to do it to save this little boy from unbearable pain. “Henry,” I whisper. “Do you want me to kneel for him?”

He shakes his head. And at once, I am so afraid that he does not want me to intercede for mercy because he is determined to order the child to be executed. I grip his hand again. “Henry!”

The boy looks up. He has bright hazel eyes just like my little brother. “Will you forgive me, Sire?” he asks. “Out of your mercy? Because I’m only ten years old? And I know that I shouldn’t have done it?”

There is a terrible silence. Henry turns from the boy and conducts me back to the dais. He takes his seat and I sit beside him. I am conscious of a sudden deep throbbing in my temples as I rack my brains as to what I can do to save this child.

Henry points at him. “You can work in the kitchens,” he says. “Spit lad. You look like you could be lively in my kitchens. Will you do it?”

The boy flushes with relief and the tears fill his eyes and spill down his rosy cheeks. “Oh, yes, Sire!” he says. “You are very good. Very merciful!”

“Do as you are bid and perhaps you will work your way up to be a cook,” Henry commends him. “Now go to work.” He snaps his fingers to a waiting servant. “Take Master Simnel to the kitchen with my compliments and tell them to set him to work.”

There is a rustle of applause and then suddenly a gale of laughter sweeps the court. I take Henry’s hand, and I am laughing too, the relief at his decision is so great. He is smiling, he is smiling at me. “You never thought that I would make war on such a child?”

I shake my head, and there are tears in my own eyes from laughter and relief. “I was so afraid for him.”

“He did nothing, he was their little standard. It is the ones behind him that I must punish. It is the ones who set him up that deserve the scaffold.” His eyes rove down the court as they talk among themselves and share their relief. He looks at my aunt, Elizabeth de la Pole, who has lost her son, who has tight hold of Maggie’s hands and they are both crying. “The real traitors will not get off so lightly,” he says ominously. “Whoever they are.”

GREENWICH PALACE, LONDON, NOVEMBER 1487

I have learned to recognize his temper, his sudden rush into rage; I have learned that it is always caused by his fear that despite the victory, despite the support of his mother, despite her declaration that God Himself is on the side of the Tudors, he will fail her and God and be cut from the throne as cruelly and as unjustly as the king he saw killed at his feet.

But I have also learned his tenderness, his love of his son, his dutiful powerful obedient submission to his mother, and—growing every day—his warmth towards me. When I disappoint him, when he suspects me, it is as if his whole world is uncertain once again. More and more he wants to love and trust me; and more and more I find that I want him to.

There is much to give me joy today. I have a son in the nursery and a husband who is secure on his throne. My sisters are safe and I am no longer haunted by dreams or ill with grief. But still, I have much to regret. Although it is my coronation day, my family are defeated. My mother is missing, enclosed in Bermondsey Abbey, my cousin John de la Pole is dead. My uncle Edward is high in the king’s trust, but is far away in Granada on crusade against the Moors, and my half brother Thomas is so careful around the king that every day he performs a sort of relentless dance on tiptoe to ensure that he doesn’t alert Henry’s suspicions. Cecily is a girl of York no longer, married to a Tudor supporter, never speaking a word without her husband’s sanction, and all my other sisters will be earmarked by My Lady the King’s Mother for Tudor loyalists; she won’t risk any one of them being made a focus for rebellion. Worst of all, worse than everything, is that Teddy is still held in the Tower and the surge of confidence that Henry felt after the battle of East Stoke has not led him to release the boy, though I have asked for it, even asked for Teddy’s freedom as a coronation day gift. His sister Maggie’s white face among my ladies is a constant reproach to me. I said that she and Teddy could come to London and that they would be safe. I said that my mother could keep them safe. I said that I would be Teddy’s guardian but I was powerless, my mother herself is enclosed, My Lady the King’s Mother has Teddy as her ward and has taken his fortune into her keeping. I did not allow for Henry’s secret terror. I did not think that a king would persecute a boy.

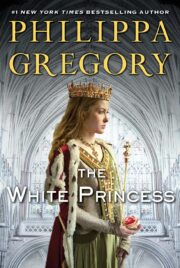

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.