“Lady Margaret will make the Warwick children her wards. And she also has plans for you. She spoke most kindly of you and of all your sisters.”

“Is Lady Margaret going to command the court?” I ask quietly.

“What plans?” Cecily demands.

“I’ll tell you later, when I know more myself,” my mother says to Cecily, and to me she remarks, “She’s to be served on bended knee, she is to be called ‘Your Grace,’ she’s to receive a royal bow.”

I make a little face of disdain. “We didn’t part the best of friends, she and I.”

“When you’re married and you are queen, she will curtsey to you, whatever name she goes by,” my mother says simply. “It doesn’t matter if she likes you or not, you’re still going to marry her son.” She turns to the younger children. “Now, I’ll show you all your rooms.”

“Aren’t we in our usual rooms?” I ask thoughtlessly.

My mother’s smile is slightly strained. “Of course we’re not in the royal rooms anymore. Lady Margaret Stanley has reserved the queen’s rooms as her own. And her husband’s family, the Stanleys, have all the best apartments. We are in the second-best rooms. You are in Lady Margaret’s old room. It seems that she and I have swapped places.”

“Lady Margaret Stanley is to have the queen’s rooms?” I ask. “Didn’t she think that I would have them?”

“Not yet, at any rate,” my mother says. “Not until the day that you marry and are crowned. Until then she is the first lady of Henry’s court, and she is anxious that everyone knows it. Apparently, she has ordered everyone to call her My Lady the King’s Mother.”

“My Lady the King’s Mother?” I repeat the strange title.

“Yes,” my mother says with a wry smile. “Not bad for a woman who was my lady-in-waiting, and who has spent the last year estranged from her husband and under house arrest for treason, don’t you think?”

We move into the second-best rooms in Westminster Palace and wait for King Henry to command our presence. He does not. He holds his court at the palace of the Bishop of London, near St. Paul’s Cathedral in the City, and every man who can pretend that he is of the House of Lancaster, or a longtime secret supporter of the Tudor cause, flocks to see him and claims a reward for his loyalty. We wait for an invitation to be presented at court, but none comes.

My mother orders new dresses for me, headdresses to make me look yet taller, new slippers to peep below the hem of the new gowns, and praises my looks. I am fair like she was, with gray eyes. She was the famously beautiful daughter of the best-looking couple in the kingdom and she says with quiet satisfaction that I have inherited the family looks.

She seems serene; but people are beginning to talk. Cecily says that we may be in the royal palace again, but it is as lonely and as quiet as being mewed up in sanctuary. I don’t bother to disagree with her, but she’s wrong. She’s so very wrong. She can’t remember sanctuary as I can; there is nothing, nothing worse than the darkness and the quiet, and knowing that you can’t get out, and fearing that anyone can come in. Last time we were in sanctuary, we could not get out for nine months; it felt like nine years, and I thought I would fade and die without sunlight. Cecily says that she, as a married woman, should not even be with us, but she should be released to rejoin her husband.

“Except that you don’t know where he is,” I say. “He’s probably run away to France.”

“At least I was married,” she says pointedly. “I didn’t bed a man married to someone else. I was not a scarlet adulteress. And at least he’s not dead.”

“Ralph Scrope of Upsall,” I reply scathingly. “Mr. Nobody of Nowhere. If you can find him, if he is still alive, you can live with him, for all I care. If he’ll have you without being told to do so. If he’ll be your husband without a royal command.”

She hunches her shoulder and turns away from me. “My Lady the King’s Mother will provide for me,” she says defensively. “I am her goddaughter. It is she who matters, who commands everything now. She will remember me.”

The weather is all wrong for the time of year, too sunny, too bright, too hot during the day and humid at night, so nobody can sleep. Nobody but me. Although I am cursed by dreams, I still cannot stop myself sleeping. I drop into darkness every night and dream that Richard has come to me, laughing. He tells me that the battle went his way and we are to be married. He holds my hands as I protest that they came and told me that Henry had won, and he kisses me and calls me a fool, a little darling fool. I wake believing it to be true, and feel a sudden sick realization when I look at the walls of the second-best bedroom, and Cecily sharing my bed, and remember that my love lies dead and cold in an unmarked grave, while his country sweats in the heat.

My maid, Jennie, who comes from a family of merchants in the City, tells me that there is terrible sickness in the crowded houses of the inner city. Then she tells me that two of her father’s apprentices have fallen sick and died.

“The plague?” I ask. At once, I step back a little from her. There is no cure for the disease and I am afraid that she carries the illness with her and the hot plague wind will blow over me and my family.

“It’s worse than the plague,” she says. “It’s not like anything anyone has seen before. Will, the first apprentice, said at breakfast that he was cold and that he ached as if he had been fighting with a singlestick all the night. My father said he could go back to his bed, and then he started to sweat; his shirt was wet with sweat, he was dripping with it. When my mother took him a pot of ale he said he was burning up and couldn’t get cool. He said he would sleep and then he didn’t waken. A young man of eighteen! Dead in an afternoon!”

“His skin?” I ask. “Did he have boils?”

“No boils, no rash,” she insists. “As I say—it’s not the plague. It’s this new illness. They call it the sweating sickness, a new plague that King Henry has brought upon us. Everyone says that his reign has started with death and won’t last. He has brought death with him. We’ll all die of his ambition. They say that he came in with sweat and will labor to keep his throne. It’s a Tudor illness, he brought it in with him. He’s cursed, everyone says so. It’s autumn but it’s as hot as midsummer, and we’re all going to sweat to death.”

“You can go home,” I say nervously. “And, Jennie, stay at home until you can be sure you are well and everyone in your house is well. My mother won’t want your service if there are sick people in your house. Don’t come back to the palace until you are free of sickness. And go home without seeing my sisters or the Warwick children.”

“But I’m well!” she protests. “And it’s a fast disease. If I had it, I would be dead before I could even tell you about it. As long as I can walk to the palace from my home, I am well enough.”

“Go home,” I command. “I’ll send for you when you can come again,” and then I go to find my mother.

She is not in the palace, not in the shuttered shade of the empty queen’s rooms, not even in the cool walks of the garden, but I find her seated on a stool at the far end of the landing stage that extends out into the river to catch the breeze that whispers along the water, listening to the lapping of the waves against the wood piling.

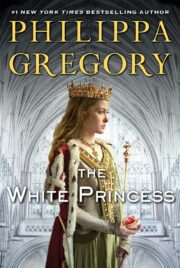

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.