Henry comes to my rooms only once during this anxious time, with a letter in his hand. “I will tell you this myself so that you don’t hear it from a York traitor,” he says unpleasantly.

I rise to my feet and my ladies melt away from my husband’s temper. They have learned, we have all learned, to keep out of the way of the Tudors, mother and son, when they are pale with fear. “Your Grace?” I say steadily.

“The King of France has chosen this moment, this very moment, to release your brother Thomas Grey.”

“Thomas!”

“He writes that he will come to support me,” Henry says bitterly. “You know, I don’t think we’ll risk that. When Thomas was last supporting me on the road to Bosworth, he changed his mind and turned his coat before we even left France. Who knows what he would have done on the battlefield? But they’re releasing him now. Just in time for another battle. What d’you think I should do?”

I hold on to the back of a chair so that my hands don’t tremble. “If he gives you his word . . .” I begin.

He laughs at me. “His word!” he says scathingly. “The York word! Would that be as binding as your mother’s word of honor? Or your cousin John’s? Your marriage vows?”

I start to stammer a reply but he puts up his hand for silence. “I’ll hold him in the Tower. I don’t want his help, and I don’t trust him free. I don’t want him talking to his mother, and I don’t want him seeing you.”

“He could . . .”

“No, he couldn’t.”

I take a breath. “May I at least write and tell my mother that her son, my half brother, is coming home?”

He laughs, a jeering unconvincing laugh. “D’you think she won’t know already? D’you think she has not paid his ransom and commanded his return?”

I write to my mother at Bermondsey Abbey. I leave the letter unsealed for I know that Henry or his mother or his spies will open it and read it anyway.

My dear Lady Mother,

I greet you well.

I write to tell you that your son Thomas Grey has been released from France and has offered his service to the king, who has decided, in his wisdom, to hold my half brother in safekeeping in the Tower of London for the time being.

I am in good health, as is your grandson.

Elizabeth

P.S. Arthur is crawling everywhere and pulling himself up on chairs so that he can stand. He’s very strong and proud of himself, but he can’t walk yet.

Henry says he must leave me and the ladies of the court, our son Arthur with his own yeomen of the guard in his nursery, and his frantically anxious mother behind the strong walls of Kenilworth Castle, muster his army, and march out. I walk with him to the great entrance gate of the castle, where his army is drawn up in battle array, behind their two great commanders: his uncle Jasper Tudor and his most reliable friend and ally, the Earl of Oxford. Henry looks tall and powerful in his armor, reminding me of my father, who always rode out to battle in the absolute certainty that he would win.

“If it goes against us, you should withdraw to London,” Henry says tightly. I can hear the fear in his voice. “Get yourself into sanctuary. Whoever they put on the throne will be your kinsman. They won’t hurt you. But guard our son. He’ll be half a Tudor. And please . . .” He breaks off. “Be merciful to my mother, see that they spare her.”

“I’m never going into sanctuary again,” I say flatly. “I’m not raising my son inside four dark rooms.”

He takes my hand. “Save yourself at any rate,” he says. “Go to the Tower. Whether they put Edward of Warwick on the throne or whether they have someone else . . .”

I don’t even ask him who else they might have to serve as a prince for York.

He shakes his head. “Nobody can tell me who might be in hiding, waiting for this moment. I have enemies but I don’t even know if they are alive or dead. I feel that I am looking for ghosts, that an army of ghosts is coming for me.” He pauses and composes himself. “At any rate, whoever they are, they are of the House of York and you will be safe with them. Our son will be safe with you. And you will give me your word that you will protect my mother?”

“You are preparing to lose?” I ask incredulously. I take his hands and I can feel the tight sinews in his fingers; he is rigid with anxiety from head to toe.

“I don’t know,” he says. “Nobody can know. If the country rises up for them then we will be outnumbered. The Irish will fight to the death and the mercenaries are well paid and have pledged themselves to this. All I have now is the men who will stand by me. My army at Bosworth has been paid off and gone home. And I can’t inspire a new army with the promise of fresh gains, or rewards. If the rebels have a true prince to put at their head, then I am probably lost.”

“A true prince?” I repeat.

We step out of the shadow of the great arch of the portcullis gate and his army raises a deep cheer as they see him. Henry waves at them and then turns to me.

“I shall kiss you,” he warns me, to ensure that we make an encouraging picture for his men. He puts his arms around me and he draws me to him. His light battle armor is hard against me; it is like hugging a man of metal. I look up into his scowling face and he brings his head down and kisses me. For a moment, uncomfortably pinioned in his arms, I am overwhelmed with pity for him.

“God bless you, my husband, and bring you safe home to me,” I say shakily.

There is a roar of pleasure from the army at the kiss, but he does not even hear it. His attention is all on me. “You mean it? I go with your blessing?”

“You do,” I say in sudden earnestness. “You do. And I shall pray that you come safely home to me. And I shall guard our son, and I shall protect your mother.”

For a moment he looks as if he would stay and speak with me. As if he wants to speak gently and truthfully to me, for the first time ever. “I have to go,” he says unwillingly.

“You go,” I say. “Send me news as soon as you can. I shall be looking for news from you, and praying that it is good.”

They bring his great warhorse, and they help him into the saddle, his standard bearer riding up beside him so the white and green flag with the Tudor red dragon ripples out over his head. The other flag is unfurled: the royal standard. Last time I saw that above an army, the man I loved, Richard, rode beneath it; and I put my hand to my heart to ease the sudden thud of pain.

“God bless you, my wife,” Henry says, but I have no smile for him anymore. He is riding the warhorse he rode at Bosworth when he stood on a hill and Richard rode to his death. He is under the Tudor flag he unfurled there, that Richard cut down in his last fatal charge.

I raise my hand to say farewell, but I am choked, and can’t repeat my blessing, and Henry wheels his horse around and leads his army out, east to where his spies tell him the great York army has taken up their position, just beyond Newark.

KENILWORTH CASTLE, WARWICKSHIRE, 17 JUNE 1487

I rise to my feet to wait for him, then I realize that My Lady will intercept him before he gets to me, so I say, “Wait here!” to my ladies and slip from the room and down the stairs to the stable yard. Just as I thought, My Lady is there in her black gown striding across the yard, as the messenger swings down from the saddle.

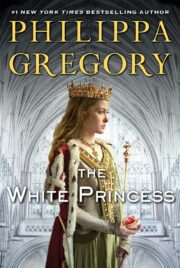

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.