My mother smiles. “We meant her for the Church,” she says. “She’s always taken it very seriously. And my nephews? John de la Pole?”

“Disappeared,” I say bluntly. Her hands grip me a little tighter.

“Arrested?” she asks.

I shake my head. “Run away,” I say shortly. “I don’t even know if you are telling me the truth when you seem not to know.”

She does not trouble herself to answer me.

“Henry says he has evidence that you are working against us.”

“Us?” she repeats.

“Against the Tudors,” I say, flushing.

“Ah,” she says. “ ‘Us Tudors.’ Do you know what exactly he knows?”

“He knows that you were writing to my aunt Margaret, and calling up York friends. He mentioned my aunt Elizabeth and even my grandmother Duchess Cecily.”

She nods. “Nothing more?”

“Mother, that is more than enough!”

“I know. But you see, Elizabeth, he might know more than this.”

“There is more than this?” I am horrified.

She shrugs. “It’s a conspiracy. Of course there is more than this.”

“Well, that’s all that he told me. Neither he nor his mother trusts me.”

She laughs out loud at that. “They hardly trust their own shadows, why would they trust you?”

“Because I am his wife and queen?”

She nods as if it hardly matters. “And where does he think John de la Pole has gone?”

“Perhaps to My Lady Aunt Margaret in Flanders?”

Clearly, this is no surprise to her. “He got safely away?”

“As far as I know. But Lady Mother—”

She softens at once at the fear in my voice. “Yes, my dear. Of course you are anxious, you will be frightened. But I think that everything is going to change.”

“What about my son?”

“Arthur was born a prince, nobody can take that from him. Nobody would want to.”

“My husband?”

Almost she laughs out loud. “Ah well, Henry was born a commoner,” she says. “Maybe he will die as one.”

“Mother, I cannot have you making war against my husband. We agreed to a peace, you wanted me to marry him. Now we have a son, and he should be the next King of England.”

She rises up and goes in three paces across the small room to look out of the window set high in the wall, to the quiet lawns and little convent church. “Perhaps so. Perhaps he will be king. I have never had a sense of it. I can’t see it myself, but it might happen.”

“Can’t you tell me?” I ask her. “Can’t you tell what’s going to happen?”

She turns and I see that her eyes are veiled and she is smiling. “As a seer, as my mother would have done? Or as a plotter? As a treasonous rebel?”

“As either!” I exclaim. “As anything! Can’t you, can’t someone tell me what is happening?”

She shakes her head. “I can’t be sure,” is all she will say.

“I have to go,” I say irritably. “I have to catch the tide back to Sheen. And then we’re going on progress.”

“Where to?” she asks.

I realize, as I tell her, that she will use this information. She will write to rebels as they muster, to enemies in England and overseas. As soon as I tell her so much as one word, that means I am working for York; I am spying for York against my own husband.

“Norwich,” I say tightly. “We’re going for Corpus Christi. Should I expect an attack now I’ve told you that?”

“Ah, so he thinks we’re invading the east coast,” she says gleefully. “So that’s what he’s expecting.”

“What?”

“He’s not going to Norwich for the pleasure of the feast. He’s going so that he can prepare the east coast for invasion.”

“They will invade? From Flanders?”

She puts a kiss on my forehead, completely ignoring my fearful questions. “Now don’t you worry about it,” she says. “You don’t need to know.”

She walks with me to the gatehouse, and then round the outside walls to where the pier runs out into the Neckinger River and my boat is waiting, bobbing on the rising tide. She kisses me and I kneel for her blessing and feel her warm hand rest gently on my hood. “God bless you,” she says sweetly. “Come and see me when you return from Norwich, if you are able to come, if you are allowed.”

“I’m going to be alone at court without you,” I remind her. “I have Cecily and I have Anne, and Maggie, but I feel alone without you. My little sisters miss you too. And My Lady the King’s Mother thinks I am plotting with you and my husband doubts me. And I have to live there, with them, all of them, being watched by them all the time, without you.”

“Not for long,” she says, her buoyant confidence unchanged. “And very soon you will come to me or—who knows—I will find a way to come to you.”

We get back to Richmond on the inflowing tide and as soon as we round the bend in the river I can see a tall slight figure waiting on the landing stage. It is the king. It is Henry. I recognize him from far away, and I don’t know whether to tell the wherry to just turn around and row away, or to go on. I should have known that he would know where I was. My uncle Edward warned me that this is a king who knows everything. I should have known that he would not accept the lie of illness without questioning my cousin Margaret, and demanding to see me.

His mother is not at his side, nor any of his court. He is standing alone like an anxious husband, not like a suspicious king. As the little boat nudges up against the wooden pilings and my groom jumps ashore, Henry puts him to one side and helps me out of the boat himself. He throws a coin to the boatman, who rings it against his teeth as if surprised to find that it is good, and then disappears into the mist of the twilight river.

“You should have told me you wanted to go and I would have sent you more comfortably on the barge,” Henry says shortly.

“I am sorry. I thought you would not want me to visit.”

“And so you thought you would get out and back without my knowing?”

I nod. There is no point denying it. Obviously I had hoped that he would not know. “Because you don’t trust me,” he says flatly. “Because you don’t think that I would let you visit her, if it was safe for you to do so. You prefer to deceive me and creep out like a spy to meet my enemy in secret.”

I say nothing. He tucks my hand into the crook of his elbow as if we were a loving husband and wife, and he makes me walk, stride by stride, with him.

“And did you find your mother comfortably housed? And well?”

I nod. “Yes. I thank you.”

“And did she tell you what she has been doing?”

“No.” I hesitate. “She tells me nothing. I told her that we were going to Norwich, I hope that wasn’t wrong?”

For a moment his hard gaze at me is softened, as if he is sorry for the tearing apart of my loyalties; but then he speaks bitterly. “No. It doesn’t matter. She will have other spies set around me as well as you. She probably knew already. What did she ask you?”

It is like a nightmare, reviewing my conversation with my mother and wondering what will incriminate her, or even incriminate me. “Almost nothing,” I answer. “She asked me if John de la Pole had left court, and I said yes.”

“Did she hazard a guess as to why he had gone? Did she know where he had gone?”

I shake my head. “I told her that it was thought that he has gone to Flanders,” I confess.

“Did she not know already?”

I shrug. “I don’t know.”

“Was he expected?”

“I don’t know.”

“Will his family follow him, do you think? His brother Edmund? His mother, Elizabeth, your aunt? His father? Are they all faithless, though I have trusted them and taken them into my court and listened to their counsels? Will they just take note of everything I said and take it to their kinsmen, my enemies?”

I shake my head again. “I don’t know.”

He releases my hand to step back and look at me, his dark eyes unsmiling and suspicious, his face hard. “When I think of the fortune that was spent on your education, Elizabeth, I am really amazed at how little you know.”

ST. MARY’S IN THE FIELDS, NORWICH, SUMMER 1487

The town is the richest in the kingdom, and every guild based on the wool business dresses up in the finest robes and pays for costumes, scenery, and horses to make a massive procession with merchants, masters, and apprentices in solemn order to celebrate the feast of the church and their own importance.

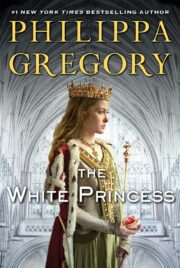

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.