I cross the room and take his hand, horrified. “Truly, I don’t know.”

He holds my hand very tightly and stares into my eyes as if trying to read my thoughts, as if he wants more than anything else in the world to know he can trust me, his wife and the mother of his child.

“Do you think John de la Pole would turn his coat and lead the army against you?” I ask, naming my own cousin, Richard’s heir. “Is it him you fear?”

“Do you know anything against him?”

I shake my head. “Nothing, I swear.”

“Worse than him,” he says shortly.

I stand before him in silence, wondering if he will name the enemy that he fears the most: the figurehead who would be more potent than a York cousin.

“Who?” I whisper.

But it is as if the ghost has entered our private room, the ghost that everyone speaks of, but no one dares to name. Superstitiously, Henry will not name him either.

“I’m ready for him,” is all he says. “Whoever it is that she has to head her army. You can tell everyone that I am ready for him.”

“Who?” I dare him to speak.

But Henry just shakes his head.

And then, the very next morning, John de la Pole is missing from the chapel at the service of Lauds. I glance down from my raised seat in the gallery and notice that his usual place is empty. He is missing at dinnertime too.

“Where is my cousin John?” I ask My Lady the King’s Mother as we wait after dinner for the priest to finish the long reading that she has commanded for all the days of Lent.

She looks at me as if I have insulted her. “You ask me?” she says.

“I ask you where is my cousin John?” I repeat, thinking that she has not heard me. “He was not at chapel this morning, and I haven’t seen him all day.”

“You should perhaps ask your mother, rather than me,” she says bitterly. “She may know. You should perhaps ask your aunt Elizabeth of York, his mother—she may know. You should ask your aunt Margaret of York, the false Dowager Duchess of Burgundy: she certainly knows, for he is on his way to her.”

I gasp and put my hand over my mouth. “Are you saying that John de la Pole is going to Flanders? How can you think such a thing?”

“I don’t think it, I know it,” she says. “I would be ashamed to say such a thing if there was any doubt. He is false, as I always said he was. He is false and he sat in our councils and heard our plans for our defense, and heard our fears of rebellion, and now he runs overseas to his aunt to tell her everything we know and everything we fear, and he asks her to put him on our throne, because she is of York, and now he says he is wholly for York, he was always wholly for York—just like you and all your family.”

“John is false?” I repeat. I cannot believe what she is saying. If it is true, then perhaps everything else that they fear is true: perhaps there is an earl, a duke, perhaps even a prince of York somewhere out there, biding his time, planning his campaign. “My cousin John has gone to Flanders?”

“False as a Yorkist,” she says, insulting me to my face. “As false as only a white rose can be, as a white rose always is.”

My Lady the King’s Mother tells me that we will go to Norwich, in the early summer since the king wants to be seen by his people, and take his justice to them. I can tell at once from the strained look in her eyes that this is a lie; but I don’t challenge her. Instead I wait for her to become absorbed in the planning of her son’s progress, and one day at the end of April I announce that I am feeling unwell and will rest in bed. I leave Maggie to guard the door to my bedroom, and to tell people that I am sleeping, and I put on my plainest gown, wrap myself in a dark cloak, and slip down to the pier outside the palace and hail a wherry boat to take me downriver.

It’s cold on the water with a biting wind that gives me an excuse to pull up my hood and wrap a scarf around my face. My groom travels with me, not knowing what we are doing but anxious because he guesses that it is forbidden. The boat goes swiftly with the tide downstream. It will be slower coming back, but I have timed my visit so that the tide will be running inland when we start for Sheen.

The wherry takes me to the abbey’s water stairs and Wes the groom jumps ashore and holds out his hands for me. The boatman promises he will wait to take me back to Sheen, the twinkle in his eyes making it clear that he thinks I am a maid of the court creeping out to meet my lover. I go up the wet steps to the little bridge that spans the watercourse and walk round the walls of the abbey till I come to the main gate and the gatehouse. I pull on the bell and wait for the porter, leaning back against the dark flint and red-brick wall.

A little door inside the great gate opens. “I want to see . . .” I break off. I don’t know what they call my mother now that she is no longer queen, now that she is under suspicion of treason. I don’t even know if she is here under her true name.

“Her Grace the Dowager Queen,” the woman says gruffly, as if Bosworth had never happened, as if Plantagenets still grew green and fresh in the garden of England. She swings open the door for me and lets me in, gesturing that the lad must wait for me outside.

“How did you know I meant her?” I ask.

She smiles at me. “You’re not the first that has come for her, and I doubt you’ll be the last,” she says, and leads me across smooth scythed turf to the cells on the west of the building. “She is a great lady; people will always be loyal to her. She’s at chapel now.” She nods at the church with the graveyard before it. “But you can wait in her cell and she will come in a moment.”

She shows me into a clean whitewashed room, with a bookshelf for my mother’s best-loved volumes, both bound manuscripts and the new print books. There is a crucifix of ivory and gold hanging on the wall, and the little nightgown that she is sewing for Arthur in a box by a chair by the fireside. It is nothing like I had imagined, and for a moment I hesitate on the threshold, weak with relief that my mother is not imprisoned in a cold tower or held in some poor nunnery, but is making her surroundings suit her—as she always does.

Through an inner door I can see her privy chamber and beyond that her curtained bed with her fine embroidered sheets. This is not a woman starving in solitary confinement; my mother is living like a queen in retirement and obviously has the whole nunnery running to her beck and call.

I sink down on a stool at the fireside until I hear a quick step on the paving stone outside and the door opens, and there is my mother, and I am in her arms and I am crying and she is hushing and soothing me and then we are seated by the fireside, and my hands are in hers and she is smiling at me, as she always does, and assuring me that everything will be well.

“But you’re not free to leave?” I confirm.

“No,” she says. “Did you ask Henry for my freedom?”

“Of course, the moment you disappeared. He said no.”

“I thought he would. I have to stay here. For now, at least. How are your sisters?”

“They’re well,” I say. “Catherine and Bridget are in the schoolroom, and I’ve told them that you have gone on a retreat. Bridget wants to join you, of course. She says the vanity of the world is too much for her.”

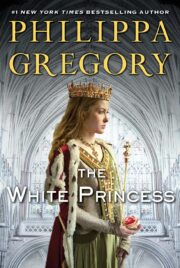

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.