I can feel my knees start to buckle, as I look over to where my mother is laughing with her nephew John de la Pole. “My mother is innocent of everything!”

Henry shakes his head. “That’s too great a claim; for I know that she is not. All it shows me is that you are lying too. You have just shown me that you will lie for her, and to me.”

They are bringing in the yule log to burn in the great hearth of the hall of Westminster Palace. It is the trunk of a great tree, a gray-barked ash, many times broader than my arms’ span. It will burn without being extinguished for all the days of Christmas. The jester is dressed all in green, riding astride on it as they drag it in, standing up and trying to balance, falling from it, bounding up again like a deer, pretending to lie before it and rolling away before someone drags it over him. Both the servants and the court are singing carols that have words of the birth of Christ set to a tune and the rhythmic beat of a drum that is older by far. This is not just the Christmas story but a celebration of the return of the sun to the earth, and that is a story as ancient as the earth itself.

My Lady smilingly watches the scene, ready as ever to frown at bawdiness or point a finger at someone who uses the revels as an excuse for bad behavior. I am surprised she has allowed this pagan bringing-in of the green, but she is always anxious to adopt the habits of the former kings of England as if to show that her rule is not that much different from those others—the real kings who went before. She hopes to pass herself and her son off as royal by mimicking our ways.

My newly married sister, Cecily, my cousin Maggie, and my younger sister Anne are among my ladies watching with me, applauding as they wrestle the great tree trunk into the wide hearth. My mother is nearby with Catherine and Bridget at her side. Bridget is clapping her hands and laughing so loudly she can hardly stand. The servants are straining at the ropes that they have tied around the massive trunk, and now the jester has torn off a piece of ivy and is pretending to beat them. Bridget’s knees give way beneath her in her delight and she is nearly crying with laughter. My Lady looks over with a slight frown. The jester’s inventions are supposed to be amusing but not excessively so. My mother exchanges a rueful look with me, but she does not restrain Bridget’s exuberant joy.

As we watch, they finally get the yule log dragged into the fireplace and rolled over into the hot embers, and then the fire boys shovel the red-hot coals around it. The ivy that is binding the trunk crisps, smokes, and flares, and then the whole thing settles into the ashes and starts to glow. A little flicker of flame licks around the bark. The yule log is alight, the Christmas celebrations can begin.

The musicians start to play and I nod to my ladies that they can dance. I take pleasure in a court of beautiful, well-behaved ladies-in-waiting, just as my mother did when she was queen. I am watching them as they go through their paces, when I see my uncle Edward Woodville, my mother’s brother, stroll into the room from a side door, and come over to my mother with a little smile. They exchange a kiss on each cheek, and then they turn together, as if they would speak privately. It’s nothing, no one but me would notice it, but I watch as he speaks briefly but intently to her, as she nods as if in agreement. He bows over her hand, and comes across to me.

“I must bid you farewell, my niece, and wish you a happy Christmas and good health for you and the prince.”

“Surely you are staying at court for Christmas?”

He shakes his head. “I am going on a journey. I’m going on a great crusade as I have long promised I would.”

“Leaving court? But where are you going, my lord uncle?”

“To Lisbon. I’m taking a ship out of Greenwich tonight, and from there to Granada. I will serve under the most Christian kings and help them drive the Moors from Granada.”

“Lisbon! And then Granada?”

At once I glance towards My Lady the King’s Mother.

“She knows,” he reassures me. “The king knows. Indeed, I am going at his bidding. She is delighted at the thought of an Englishman on crusade against the heretic, and he has a few little tasks for me on the way.”

“What tasks?” I cannot stop myself lowering my voice to a whisper. My uncle Edward is one of the few members of our family trusted by the king and his mother. He was in exile with Henry, a sworn friend when Henry had few sworn friends. He escaped from my uncle Richard with two ships of his fleet, and was among the first to join Henry in Brittany. My uncle’s constant, reliable presence at the exiled little court assured Henry that we, the fallen royal family scuffling in sanctuary, were his allies. As Richard took the throne and made himself king, Henry, the pretender, was encouraged to trust us by the steady presence of my uncle Edward, fiercely loyal to his sister, the former queen.

He was not the only York loyalist who made his way to Henry’s court of turncoats and exiles. My half brother Thomas Grey was there too, keeping our claim before Henry, reminding him of his promises to marry me. I can only imagine Henry’s horror when he woke one morning and his scant servants at his tiny court told him that Thomas Grey’s horse was gone from the stables and his bed was untouched and he realized that we had changed sides and were for Richard. Henry and Jasper sent riders after Thomas Grey and they captured him. They held him as a prisoner for my mother’s goodwill—fearing that nothing could guarantee her goodwill—and they still hold him in France, a guest of honor with a promise to return but still without a horse to ride home.

My uncle Edward played a longer game, a deeper game. He stayed with Henry and invaded with him at Bosworth, and served beside him at the battle. He serves him still. Henry never forgets his friends, nor does he forget those who changed their minds during his time of exile. I think he will never again trust my brother Thomas, but he loves my uncle Edward and calls him his friend.

“He is sending me on a diplomatic mission,” my uncle says.

“To the King of Portugal? Surely Lisbon is not on the way to Granada?”

He spreads his hand and smiles at me, as if I might share a joke, or a secret. “Not directly to the King of Portugal. He wants me to see something that has arisen, appeared at the Portuguese court.”

“What sort of thing?”

He drops on his knee and kisses my hand. “A secret thing, a precious thing,” he says gleefully, then he rises up and goes. I look around for my mother and see her smiling at him as he works his way through the laughing, dancing, celebrating court. She watches his swift bow to Henry and the king’s discreet acknowledgment, and then my uncle slips through the great doors of the hall, as quiet as any spy.

That night Henry comes to my bed. He will come every single night only excepting the week of my course, or the nights of holy fasts or saints’ days. We have to conceive another child, we have to have another son. One is not enough to ensure the safety of the line. One is not enough to keep a new king steady on his throne. One son does not demonstrate powerfully enough the blessing of God on the new family.

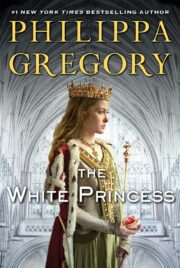

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.