This is fortune’s wheel—as my grandmother Jacquetta would say. Fortune’s wheel that takes you very high and then throws you very low, and there is nothing you can do but face the turn of it with courage. I remember clearly enough that as a little girl I could not find that courage.

When I was seventeen and the favorite of my father’s court, the most beautiful princess in England with everything before me, my father died and we fled back into sanctuary, for fear of his brother, my uncle Richard. Nine long months we waited in sanctuary, squabbling with one another, furious at our own failure, until my mother came to terms with Richard and I was freed into the light, to the court, to love. For the second time I came out of the dark like a ghost returning to life. Once again I blinked in the warm light of freedom like a hooded hawk suddenly set free to fly, and I swore I would never again be imprisoned. Once again, I am proved wrong.

My pains start at midnight. “It’s too early,” one of my women breathes in fear. “It’s at least a month too early.” I see a swift glance between those habitual conspirators, my mother and My Lady the King’s Mother. “It is a month too early,” My Lady confirms loudly for anyone who is counting. “We will have to pray.”

“My Lady, would you go to your own chapel and pray for our daughter?” my mother asks quickly and cleverly. “An early baby needs intercession with the saints. If you would be so good as to pray for her in her time of travail?”

My Lady hesitates, torn between God and curiosity. “I had thought to help her here. I thought I should witness . . .”

My mother shrugs at the room, the midwives, my sisters, the ladies-in-waiting. “Earthly tasks,” she says simply. “But who can pray like you?”

“I’ll get the priest, and the choir,” My Lady says. “Send me news throughout the night. I’ll get them to wake the archbishop. Our Lady will hear my prayers.”

They open the door for her and she goes out, excited by her mission. My mother does not even smile as she turns back to me and says, “Now, let’s get you walking.”

While My Lady labors on her knees, I labor all the night, until at dawn I turn my sweating face to my mother and say, “I feel strange, Lady Mother. I feel strange, like nothing I have felt before. I feel as if something terrible is about to happen. I’m afraid, Mama.”

She has laid aside her headdress, her hair is in a plait down her back, she has walked all the night beside me and now her tired face beams. “Lean on the women,” is all she says.

I had thought it would be a struggle, having heard all the terrible stories that women tell each other about screaming pain and babies that have to be turned, or babies that cannot be born and sometimes, fatally, have to be cut out; but my mother orders two of the midwives to stand on either side of me to bear me up, and she takes my face in her cool hands and looks into my eyes with her gray gaze and says quietly, “I am going to count for you. Be very still, beloved, and listen to my voice. I am going to count from one to ten and as I count you will find your limbs get heavier and your breathing gets deeper and all you can hear is my voice. You will feel as if you are floating, as if you are Melusina on the water, and you are floating down a river of sweet water and you will feel no pain, only a deep restfulness like sleep.”

I am watching her eyes and then I can see nothing but her steady expression and hear nothing but her quiet counting. The pains come and go in my belly, but it feels like a long way away and I float, as she promised that I would, as if on a current of sweet water.

I can see the steadiness of her gaze, and the illumination of her face, and I feel that we are in a time of unreality, as if she is making magic around us with her reliable quiet count which seemed to go slowly and take an eternity.

“There is nothing to fear,” she says to me softly. “There is never anything to fear. The worst fear is of fear itself, and you can conquer that.”

“How?” I murmur. It feels as if I am talking in my sleep, floating down a stream of sleep. “How can I conquer the worst fear?”

“You just decide,” she says simply. “Just decide that you are not going to be a fearful woman and when you come to something that makes you apprehensive, you face it and walk towards it. Remember—anything you fear, you walk slowly and steadily towards it. And smile.”

Her certainty and the description of her own courage make me smile even though my pains are coming and then easing, faster now, every few minutes or so, and I see her beloved beam in reply as her eyes crinkle.

“Choose to be brave,” she urges me. “All the women of your family are as brave as lions. We don’t whimper and we don’t regret.”

My stomach seems to grip and turn. “I think the baby is coming,” I say, and I breathe deeply.

“I think so too,” she says, and turns to the midwives who hold me up, one under each arm, while the third kneels before me and listens with her ear against my straining belly.

“Now,” she says.

My mother says to me: “Your baby is ready, let him come into the world.”

“She needs to push,” one of the midwives says sharply. “She needs to struggle. He has to be born in travail and pain.”

My mother overrules her. “You don’t need to struggle,” she says. “Your baby is coming. Help him come to us, open your body and let him come into the world. You give birth, you don’t force birth or besiege it. It’s not a battle, it’s an act of love. You give birth to your child and you can do it gently.”

I can feel the sinews of my body opening and stretching. “It’s coming!” I say, suddenly alert. “I can feel . . .”

And then there is a rush and a thrust and an inescapable sense of movement, and then the sharp crying noise of a child and my mother smiling, though her eyes are filled with tears, and she says to me: “You have a baby. Well done, Elizabeth. Your father would be proud of your courage.”

They release me from the grip they have taken on my arms, and I lie down on the day bed and turn to where the woman is wrapping a little wriggling bloody bundle and I hold out my arms, saying impatiently: “Give me my baby!” I take it, with a sense of wonder that it is a baby, so perfectly formed, with brown hair and a rosy mouth open to bellow, and a cross flushed face. But my mother pulls back the linen that they have wrapped it in, and shows me the perfect little body.

“A boy,” she says, and there is neither triumph nor joy in her voice, just a deep wonder, though her voice is hoarse with weariness. “God has answered Lady Margaret’s prayers again. His ways are mysterious indeed. You have given the Tudors what they need: a boy.”

The king himself has been waiting all night outside the door for the news, like a loving husband who cannot wait for a messenger. My mother throws her robe over her stained linen shift and goes out to tell him of our triumph, her head high with pride. They send word to My Lady the King’s Mother in the chapel that her prayers have been answered and God has secured the Tudor line. She comes in as the women are helping me into the great state bed to rest, and washing and swaddling the baby. His wet nurse curtseys and shows him to My Lady, who reaches for him greedily, as if he were a crown in a hawthorn bush. She snatches him up and holds him to her heart.

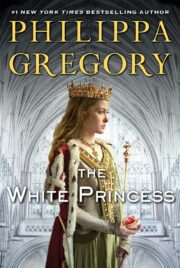

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.