“You know, I should be king,” ten-year-old Edward says, tugging at my sleeve. “I’m next, aren’t I?”

I turn to him. “No, Teddy,” I say gently. “You cannot be king. It’s true that you are a boy of the House of York and Uncle Richard once named you as his heir; but he is dead now, and the new king will be Henry Tudor.” I hear my voice quaver as I say “he is dead,” and I take a breath and try again. “Richard is dead, Edward, you know that, don’t you? You understand that King Richard is dead? And you will never be his heir now.”

He looks at me so blankly that I think he has not understood anything at all, and then his big hazel eyes fill with tears, and he turns and goes back to copying his Greek alphabet on his slate. I stare at his brown head for a moment and think that his dumb animal grief is just like mine. Except that I am ordered to talk all the time, and to smile all the day.

“He can’t understand,” Cecily says to me, keeping her voice low so his sister Maggie cannot hear. “We’ve all told him, over and over again. He’s too stupid to believe it.”

I glance at Maggie, quietly seating herself beside her brother to help him to form his letters, and I think that I must be as stupid as Edward, for I cannot believe it either. One moment Richard was marching at the head of an invincible army of the great families of England; the next they brought us the news that he had been beaten, and that three of his trusted friends had sat on their horses and watched him lead a desperate charge to his death, as if it were a sunny day at the joust, as if they were spectators and he a daring rider, and the whole thing a game that could go either way and was worth long odds.

I shake my head. If I think of him, riding alone against his enemies, riding with my glove tucked inside his breastplate against his heart, then I will start to cry; and my mother has commanded me to smile.

“So we are going to London!” I say, as if I am delighted at the prospect. “To court! And we will live with our Lady Mother at Westminster Palace again, and be with our little sisters Catherine and Bridget again.”

The two orphans of the Duke of Clarence look up at this. “But where will Teddy and me live?” Maggie asks.

“Perhaps you will live with us too,” I say cheerfully. “I expect so.”

“Hurrah!” Anne cheers, and Maggie tells Edward quietly that we will go to London, and that he can ride his pony all the way there from Yorkshire like a little knight at arms, as Cecily takes me by the elbow and draws me to one side, her fingers nipping my arm. “And what about you?” she asks. “Is the king going to marry you? Is he going to overlook what you did with Richard? Is it all to be forgotten?”

“I don’t know,” I say, pulling away. “And as far as we are concerned, nobody did anything with King Richard. You, of all people, my sister, would have seen nothing and will speak of nothing. As for Henry, I suppose whether he is going to marry me or not is the one thing that we all want to know. But only he knows the answer. Or perhaps two people: him—and that old crone, his mother, who thinks she can decide everything.”

ON THE GREAT NORTH ROAD, AUTUMN 1485

Edward is excited by the journey, reveling in the freedom of the Great North Road, and taking pleasure in the people who turn out all along the way to see what is left of the royal family of York. Every time our little procession halts, people come out to bless us, doffing their caps to Edward as the only remaining York heir, the only York boy, even though our house is defeated and people have heard that there is to be a new king on the throne—a Welshman that nobody knows, a stranger come in uninvited from Brittany or France or somewhere over the narrow seas. Teddy likes to pretend to be the rightful king, going to London to be crowned. He bows and waves his hand, pulls off his bonnet, and smiles when the people tumble out of their houses and shop doorways as we ride through the small towns. Although I tell him daily that we are going to the coronation of the new King Henry, he forgets it as soon as someone shouts, “À Warwick! À Warwick!”

Maggie, his sister, comes to me the night before we enter London. “Princess Elizabeth, may I speak with you?”

I smile at her. Poor little Maggie’s mother died in childbirth and Maggie has been mother and father to her brother, and the mistress of his household, almost before she was out of short clothes. Maggie’s father was George, Duke of Clarence, and he was executed in the Tower on the orders of my father, at the urging of my mother. Maggie never shows any sign of a grudge, though she wears a locket around her neck with her mother’s hair in it, and on her wrist, a little charm bracelet with a silver barrel as a memorial for her father. It is always dangerous to be close to the throne; even at twelve, she knows this. The House of York eats its own young like a nervous cat.

“What is it, Maggie?”

Her little forehead is furrowed. “I am anxious about Teddy.”

I wait. She is a devoted sister to the little boy.

“Anxious about his safety.”

“What do you fear?”

“He is the only York boy, the only heir,” she confides. “Of course there are other Yorks, the children of our aunt Elizabeth, Duchess of Suffolk; but Teddy is the only son left of the sons of York: your father King Edward, my father the Duke of Clarence, and our uncle King Richard. They’re all dead now.”

I register the familiar chord of pain that resonates in me at his name, as if I were a lute, strung achingly tight. “Yes,” I say. “Yes, they are all dead now.”

“From those three sons of York, there are no other sons anymore. Our Edward is the only boy left.”

She glances at me, uncertainly. Nobody knows what happened to my brothers Edward and Richard, who were last seen playing on the green before the Tower of London, waving from the window of the Garden Tower. Nobody knows for sure; but everyone thinks they are dead. What I know, I keep a close secret, and I don’t know much.

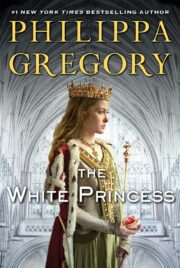

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.