I hand her the letter, surprised at my own sense of relief. Of course I want the restoration of my house and the defeat of Richard’s enemy—sometimes I feel a thrill of violent desire at the sudden vivid image of Henry falling from his horse and fighting for his life on the ground in the middle of a cavalry charge as the hooves thunder by his head—and yet, this letter brings me the good news that my husband has survived. I am carrying a Tudor in my belly. Despite myself, I can’t wish Henry Tudor dead, thrown naked and bleeding across the back of his limping horse. I married him, I gave him my word, he is the father of my unborn child. I might have buried my heart in an unmarked grave, but I have promised my loyalty to the king. I was a York princess, but I am a Tudor wife. My future must be with Henry. “It’s over,” I repeat. “Thank God it’s over.”

“It’s not over at all,” my mother quietly disagrees. “It’s just beginning.”

PALACE OF SHEEN, RICHMOND, SUMMER 1486

My Lady the King’s Mother makes representation to the Holy Father through her cat’s-paw John Morton, and the helpful word comes from Rome that the laws on sanctuary are to be changed to suit the Tudors. Traitors may not go into hiding behind the walls of the Church anymore. God is to be on the side of the king and to enforce the king’s justice. My Lady wants her son to rule England inside sanctuary, right up to the altar, perhaps all the way to heaven, and the Pope is persuaded to her view. Nowhere on earth can be safe from Henry’s yeomen of the guard. No door, not even one on holy ground, can be closed in their hard faces.

The might of English law is to favor the Tudors too. The judges obey the new king’s commands, trying men who followed the Staffords or Francis Lovell, pardoning some, punishing others, according to their instructions from Henry. In my father’s England the judges were supposed to make up their own minds, and a jury was supposed to be free of any influence but the truth. But now the judges wait to hear the preferences of the king before reaching their sentences. The statements of the accused men, even their pleas of guilt, are of less importance than what the king says they have done. Juries are not even consulted, not even sworn in. Henry, who stayed away from the fighting, rules at long distance through his spineless judges, and commands life and death.

Not until August does the king come home and at once he moves the court away from the city that threatened him, out of town to the beautiful newly restored Palace of Sheen by the river. My uncle Edward comes with him, and my cousin John de la Pole, riding easily in the royal train, smiling at comrades who do not wholly trust them, greeting my mother as a kinswoman in public and never, never talking with her in private, as if they have to demonstrate every day that there are no whispered secrets among the Yorks, that we are all reliably loyal to the House of Tudor.

There are many who are quick to say that the king does not dare to live in London, that he is afraid of the twisting streets and the dark ways of the city, of the sinuous secrets of the river and those who silently travel on it. There are many who say he is not sure of the loyalty of his own capital city and that he does not trust his safety within its walls. The trained bands of the city keep their own weapons to hand, and the apprentices are always ready to spring up and riot. If a king is well loved in London, then he has a wall of protection around him, a loyal army always at his doors guarding him. But a king with uncertain popularity is under threat every moment of the day, anything—hot weather, a play that goes wrong, an accident at a joust, the arrest of a popular youth—can trigger a riot which might unseat him.

Henry insists that we must move to Sheen as he loves the countryside in summer and exclaims at the beauty of the palace and the richness of the park. He congratulates me on the size of my belly and insists that I sit down all the time. When we walk together into dinner he demands that I lean heavily on his arm, as if my feet are likely to fail underneath me. He is tender and kind to me, and I am surprised to find that it is a relief to have him home. His mother’s anguished vigilance is soothed by the sight of him, the constant uneasiness of being a new court in an uncertain country is eased, and the court feels more normal with Henry riding out to hunt every morning and coming home boasting of fresh venison and game every night. His looks have improved during his long summertime journey around England, his skin warmed by the sunshine, and his face more relaxed and smiling. He was afraid of the North of England before he went there, but once the worst of his fears did indeed happen, and he survived it, he felt victorious once again.

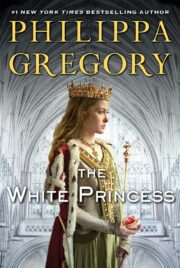

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.