Some nights he comes in late from sitting with his mother, some nights he comes in a little drunk from laughing with his friends. He has very few friends—only those from the years of exile, men he knows that he can trust for they were there when he was a pretender and they were as desperate as him. He admires only three men: his uncle Jasper, and his new kinsmen Lord Thomas Stanley and Sir William Stanley. They are his only advisors. This night he comes in early and thoughtful, a sheaf of papers in his hands, requests from men who supported him and now want a share in the wealth of England—the barefoot exiles queuing for dead men’s shoes.

“Husband, I would talk with you.” I am sitting at the fireside in my nightgown, a red robe over my shoulders, my hair brushed loose. I have some warmed ale for him and some small meat pies.

“It’ll be about your mother,” he guesses at once disagreeably, taking in my preparations in one quick glance. “Why else would you attempt to make me comfortable? Why else would you go to the trouble to look irresistible? You know you are more beautiful than any woman I have ever seen in my life before. Whenever you wear red and spread out your hair, I know that you hope to entrap me.”

“It is about her,” I say, not at all abashed. “I don’t want her to be sent away from me. I don’t want her to go to Scotland. And I don’t want her to have to marry again. She loved my father. You never saw them together, but it was a marriage of true love, a deep love. I don’t want her to have to wed and bed another man—a man fourteen years younger than her, and our enemy . . . it’s . . . it’s . . .” I break off. “Truly, it is an awful thing to ask of her.”

He sits in the chair facing the fire and says nothing for a moment, looking at the logs that are burning down to red embers.

“I understand that you don’t want her to go,” he says quietly. “And I’m sorry for that. But half of this country still supports the House of York. Nothing has changed for them. Sometimes I think that nothing will ever change them. Defeat does not alter them, it just makes them bitter and more dangerous. They supported Richard and they won’t change sides for me. Some of them dream that your brothers are still alive, and whisper about a prince over the water. They see me as a newcomer, an invader. D’you know what they call me in the streets of York? My spies write to tell me. They call me Henry the Conqueror, as if I were William of Normandy—a foreign bastard come again. As if I am another foreign bastard. A pretender to the throne. And they hate me.”

I stir, about to make up some reassuring lie; but he holds out his hand and I put my cold hand in his and he pulls me towards him, to stand before him.

“If anyone, any man at all, stood up with a claim to the throne, and he came from the House of York, he would muster a thousand, perhaps many thousands of men,” he says. “Think of it. You could put up a dog under the banner of the white rose and they would turn out and fight to the death for it. And I would be no further on. Dog or prince, I would have the whole battle to fight all over again. It would be like invading all over again. It would be like being sleepless before the battle of Bosworth again and dreaming of the day over and over again. Except for one thing—and it is all worse: this time I would have no French army, I would have no supporters from Brittany, I would have no foreign money to hire troops, I would have no well-trained mercenaries. I would have no foolish optimism of a lad in battle for the first time. This time, I would be on my own. This time, I would have no supporters but those men who have joined my court since I won the battle.”

He sees the contempt for them in my face and he nods, agreeing with me. “I know: timeservers,” he says. “Yes, I know. Men who join the winning side. D’you think I don’t realize that they would have been Richard’s greatest friends if he had won at Bosworth? D’you think I don’t know that they would flock to whoever won a battle between me and a new pretender? D’you think I don’t know that every one of them is my friend, my dearest friend, only because I won that single battle on that particular day? D’you think I don’t count the very, very few who were with me in Brittany against the very, very many who are with me in London? D’you think I don’t know that any new pretender who beat me would be just as I am, he would do just what I have done—change the law, distribute wealth, try to make and keep loyal friends.”

“What new pretender?” I whisper, picking out the one word from his worries. At once I am frozen with fear that he has heard a rumor of a boy somewhere, hidden in Europe, perhaps writing to my mother. “What d’you mean, a new pretender?”

“Anyone,” he says harshly. “Christ Himself can’t know who is out there in hiding! I keep hearing of a boy, I keep getting whispers of a boy, but nobody can tell me where he is or what he claims to be. God knows what the people would do, if they heard just half of the stories that I have to listen to every day. John de la Pole, your cousin, may have sworn loyalty to me, but his mother is your father’s sister, and he was named as Richard’s heir—I don’t know if I can trust him. Francis Lovell—Richard’s greatest friend—is hidden away in sanctuary and nobody knows what he wants or what he plans, or who he is working with. God help me, I have moments when I even doubt your uncle Edward Woodville, and he has been in my household since Brittany. I am delaying the release of your half brother Thomas Grey because I fear that he won’t come home to England a loyal subject but just be another recruit for them—whoever they are, whoever they are waiting for. Then there is Edward Earl of Warwick, in your mother’s household, studying what exactly? Treason? I am surrounded by your family and I don’t trust any of them.”

“Edward is a child,” I say quickly, breathless with relief that at least he has no news of a York prince, no knowledge of his whereabouts, no revealing detail of his looks, his education, his claim. “And completely loyal to you, as is my mother now. We gave you our word that Teddy would never challenge you. We promised him to you. He has sworn loyalty. Of all of us, above us all, you can trust him.”

“I hope so,” he says. “I hope so.” He looks drained by his fears. “But even so—I have to do everything! I have to hold this country to peace, to secure the borders. I am trying to do a great thing here, Elizabeth. I am trying to do what your father did, to establish a new royal family, to set its stamp on the country, to lead the country to peace. Your father could never get an established peace with Scotland though he tried, just as I am trying. If your mother would go to Scotland for us, and hold them to an alliance, she would do you a service, and me a service, and her grandson would be in debt to her all his life for his safe inheritance of England. Think of that! Giving our son his kingdom with borders at peace! And she could do it!”

“I have to have her with me!” It is a wail like that of a child. “You wouldn’t send your own mother away. She has to be with you all the time! You keep her close enough!”

“She serves our house,” he says. “I am asking your mother to serve our house too. And she is a beautiful woman still, and she knows how to be queen. If she were Queen of Scotland, we would all be safer.”

He stands. He puts his hands on either side of my thickening waist and looks down into my troubled face. “Ah, Elizabeth, I would do anything for you,” he says gently. “Don’t be troubled, not when you are carrying our son. Please don’t cry. It’s bad for you. It’s bad for the baby. Please—don’t cry.”

“We don’t even know if it is a son,” I say resentfully. “You say it all the time, but it doesn’t make it so.”

He smiles. “Of course it is a boy. How could a beautiful girl like you make anything for me but a handsome firstborn son?”

“I have to have my mother with me,” I stipulate. I look up into his face and catch a glimpse of an emotion I never expected to see. His hazel eyes are warm, his mouth is tender. He looks like a man in love.

“I need her in Scotland,” he says, but his voice is soft.

“I cannot give birth without her here. She has to be with me. What if something goes wrong?”

It is my greatest card, a trump.

He hesitates. “If she is with you for the birth of our boy?”

Sulkily I nod my head. “She must be with me till he is christened. I will be happy in my confinement only if she is with me.”

He drops a kiss on the top of my head. “Ah, then I promise,” he says. “You have my word. You bend me to your will like the enchantress you are. And she can go to Scotland after the birth of your baby.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, MARCH 1486

She solves the problem by drowning him in jewels. He never goes out without a precious brooch in his hat, or a priceless pearl at his throat. He never rides without gloves encrusted with diamonds, or a saddle with stirrups of gold. She bedecks him in ermine as if she were decorating a relic for an Easter procession; and still he looks like a young man stretched beyond his abilities, living beyond his means, ambitious and anxious all at once, his face pale against purple velvet.

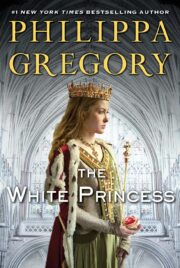

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.