It is warm with a long-established fire of smoldering logs and scented pinecones in the hearth, and my mother gives me a drink of specially brewed wedding ale.

“Are you nervous?” Cecily asks, her tone as sweet as mead. We still don’t have a date for her wedding day, and she is anxious that no one forget that she must come next. “I am sure that I will be nervous, on my wedding night. I shall be a nervous bride, I know, when it is my turn.”

“No,” I say shortly.

“Why don’t you help your sister into bed?” my mother suggests to her, and Cecily turns back the covers and gives me an upward push into the high bed. I settle myself against the pillows and swallow down my apprehension.

We can hear the king and his friends approaching the door. The archbishop comes in first, to sprinkle holy water and pray over the marriage bed. Behind him comes Lady Margaret, a big ivory crucifix tightly in her hands, and behind her comes Henry, looking flushed and smiling among a band of men who slap him on the back and tell him that he has won the finest trophy in all of England.

One freezing look from Lady Margaret warns everyone that there are to be no bawdy jests. The page boy turns back the covers, the king’s men in waiting take off his thick bejeweled robe, Henry in his beautifully embroidered white linen nightshirt slips between the sheets beside me, and we both sit up and sip our wedding ale like obedient children at bedtime while the archbishop finishes his prayers and steps back.

Reluctantly, the wedding guests go out, my mother gives me a quick farewell smile and shepherds my sisters away. Lady Margaret is the last to leave and as she goes to the door I see her look back at her son, as if she has to stop herself from coming back in to embrace him once more.

I remember that he told me of all the years when he went to sleep without her kiss or her blessing, and that she loves now to see him to his bed. I see her hesitating at the threshold as if she cannot bear to leave him, and I give her a smile, and I stretch out my hand and rest it lightly on her son’s shoulder, a gentle proprietorial touch. “Good night, Lady Mother,” I say. “Good night from us both.” I let her see me take her son’s fine linen collar in my fingers, the collar she embroidered herself in white-on-white embroidery, and I hold it as if it were the leash of a hunting dog who is wholly mine.

For a moment she stands watching us, her mouth a little open, drawing a breath, and as she stays there, I lean my head towards Henry as if I am going to rest it on his shoulder. He is smiling proudly, his face flushed, thinking that she is enjoying the sight of her son, her adored only son, in his wedding bed, a beautiful bride, a true princess, beside him. Only I understand that the sight of me, with his shoulder under my cheek, smiling in his bed, is eating her up with jealousy as if a wolf had hold of her belly.

Her face is twisted as she closes the door on us, and as the lock clicks shut and we hear the guardsmen ground their pikes, we both breathe out, as if we have been waiting for this moment when we are finally alone. I raise my head and take my hand from his shoulder, but he catches it and presses my fingers to his collarbone. “Don’t stop,” he says.

Something in my face alerts him to the fact that it was not a caress but a false coin. “Oh, what were you doing? Some spiteful girlish trick?”

I take my hand back. “Nothing,” I say stubbornly.

He looms towards me and for a moment I am afraid that I have angered him, and he is going to insist on confirming the marriage by bedding me, inspired by anger, wanting to give me pain for pain. But then he remembers the child that I carry, and that he may not touch me while I am pregnant, and he gets up bristling with offense, and throws his beautiful wedding robe around his shoulders and stirs the fire, draws a writing table to the chair and lights the candle. I realize that the whole day has been spoiled for him by this moment. He can declare a day ruined by the mishap of a minute and he will remember the minute and forget the day. He is always so anxious that he seeks disappointment—it confirms his pessimism. Now he will remember everything, the cathedral, the ceremony, the feasting, the moments that he enjoyed, through a veil of resentment, for the rest of his life.

“There was I, fool that I am, thinking that you were being loving to me,” he says shortly. “I thought you were touching me tenderly. I thought that our marriage vows had moved your heart. I thought that you were resting your head on my shoulder for affection. Fool that I am.”

I can make no reply. Of course I was not being loving to him. He is my enemy, the murderer of my betrothed lover. He is my rapist. How should he dream that there could ever be affection between us?

“You can sleep,” he throws over his shoulder. “I am going to look at some requests. The world is filled with people who want something from me.”

I care absolutely nothing for his ill temper. I will never allow myself to care for him, whether he is angry, or even—perhaps as now—hurt, and by me. He can comfort himself or sulk all night, just as he pleases. I pull the pillow down under my head, smooth out my nightgown across my rounded belly, and turn my back to him. Then I hear him say, “Oh! I forgot something.” He comes back to the bed and I glance over my hunched shoulder and I see, to my horror, that he has a knife in his hand, unsheathed, the firelight glinting on the bare blade.

I freeze in fear. I think, dear God, I have angered him so badly that he is going to kill me now in revenge for making him a cuckold, and what a scandal there will be, and I did not say good-bye to my mother. Then I think irrelevantly that I lent a necklace to little Margaret of Warwick to wear on my wedding day, and I should like her to know that she can keep it if I am going to die, and then finally I think—oh God, if he cuts my throat now, then I will be able to sleep without dreaming of Richard. I think perhaps there will be a sudden terrible pain and then I will dream no more. Perhaps the stab of the dagger will thrust me into Richard’s arms, and I will be with him in a sweet sleep of death together, and I will see his beloved smiling face and he will hold me and our eyes will close together. At the thought of Richard, of sharing death with Richard, I turn towards Henry and the knife in his hand.

“You’re not afraid?” he asks curiously, staring at me as if he is seeing me for the very first time. “I’m standing over you with a dagger and yet you don’t even flinch? Is it true then? What they say? That your heart is so broken that you wish for death?”

“I won’t beg for my life, if that’s what you’re hoping,” I say bitterly. “I think I’ve had my best days and I never expect to be happy again. But no, you’re wrong. I want to live. I would rather live than die and I would rather be queen than dead. But I’m not frightened of you or your knife. I’ve promised myself that I will never care for anything that you say or do. And if I were afraid, I would rather die than let you see it.”

He laughs shortly and says, as if to himself, “Stubborn as a mule, just as I warned my Lady Mother . . .” Then he says out loud, “No, this is not to cut your pretty throat but only your foot. Give me your foot.”

Unwillingly, I stretch out my foot, and he throws back the rich covers of the bed. “Seems a pity,” he says to himself. “You do have the most exquisite skin, and the arch of your instep is just kissable—it’s ridiculous that one should think of it, but any man would want to kiss just here . . .” and then he makes a quick painful slash that makes me flinch and cry out in pain.

“You hurt me!”

“Hold still,” he says, and squeezes my foot over the sheets so that two, three drops of blood fall on the whiteness, then he hands me a linen cloth. “You can bind it up. It will hardly show in the morning, it was nothing more than a scratch, and anyway you will put on stockings.”

I tie the cloth around my foot and look at him. “There’s no need to look so aggrieved,” he says. “That has saved your reputation. They’ll look at the sheets in the morning and there’s the stain that shows that you bled like a virgin on your wedding night. When your belly shows, we will say that he was a wedding-night baby, and when he is born we will say that he is an eight-month baby, come early.”

I put my hand to my belly where I can feel nothing more than a couple of handfuls of extra fat. “What would you know about an eight-month baby?” I ask. “What would you know about a show on the sheets?”

“My mother told me,” he says. “She told me to cut your foot.”

“I have so much to thank her for,” I say bitterly.

“You should do. For she told me to do this to make him into a honeymoon baby,” Henry says with grim humor. “A honeymoon baby, a blessing, and not a royal bastard.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, FEBRUARY 1486

Mouth downturned, eyes hostile, I just look at him.

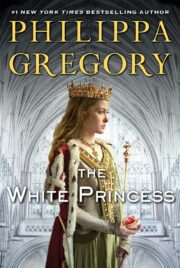

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.