“Why ever not?” I say, diverted.

He has the grace to blush. “She likes to see me to my bed,” he admits. “She likes to kiss me good night.”

“She kisses you good night?” I query, thinking of the hard heart of the woman who could send her son to rape me and then wait up to kiss him good night.

“There were so many years when she couldn’t kiss me before I slept,” he says quietly. “There were so many years when she didn’t know where I slept, or even if I was safely asleep at all. She likes to mark my forehead with the sign of a cross and kiss me good night. But tonight when she comes to bless me I will tell her that you are with child and I am hoping for a son!”

“I think I am with child,” I say cautiously. “But it is early days. I can’t be sure. Don’t tell her that I said I was sure.”

“I know, I know. And you will think I have been selfish, my mind only on the Tudor house. But if you have a boy, your family is of the royal house of England and your son will be king. You are in the position you were born to hold, and the wars of the cousins are ended forever, with a wedding and a baby. This is how it should be. This is the only happy ending that there can be, for this war and this country. You will have brought us all to peace.” He looks at me as if he wants to take me in his arms and kiss me. “You have brought us to peace and a happy ending.”

I hunch my shoulder against him. “I had thought of other endings,” I say, remembering the king that I loved, who had wanted me to have his son, and who said that we would call him Arthur, in honor of Camelot, a royal heir who was not made in cold determination and bitterness, but with love in warm secret meetings.

“Even now there could be other endings,” he says cautiously, taking my hand and holding it gently. He lowers his voice as if there could be eavesdroppers in this, our most private room. “We still have enemies. They are hidden but I know they are there. And if you have a girl it’s no good to me, and all this will have been for nothing. But we will work and pray that it is a Tudor boy that you are carrying. And I will tell my mother that she can arrange our wedding. At least we know that you are fertile. Even if you fail and have a girl this time, we know that you can bear a child. And next time perhaps we’ll get a boy.”

“What would you have done if I had not conceived a child?” I ask curiously. “If you had taken me but no baby had come?” I begin to realize that this man and his mother have a plan for everything, they are always in readiness.

“Your sister,” he says shortly. “I would have married Cecily.”

I gasp in shock. “But you said she was to marry Sir John Welles?”

“Yes. But if you were barren I would still need to marry a woman who could give me a son from the House of York. It would have had to be her. I would have canceled her wedding to Sir John, and had her for my wife.”

“And would you have raped her too?” I spit, pulling my hand away. “First me and then my sister?”

He raises his shoulders and spreads out his hands, a gesture entirely French, not like an Englishman at all. “Of course. I would have had no choice. I have to know that any wife can give me a son. Even you must see that I’m not taking the throne for myself, but to make a new royal family. I am not taking a wife for myself but to make a new royal family.”

“Then we are like the poorest country people,” I say bitterly. “They only marry when a baby is on the way. They always say you only buy a heifer in calf.”

He chuckles, not at all abashed. “Do they? Then I’m an Englishman indeed.” He ties the laces at his belt and laughs. “In the end I am an English peasant! I shall tell my Lady Mother tonight and she’ll be sure to come and see you tomorrow. She has prayed for this every night that I have been doing my business here.”

“She prayed while you were raping me?” I ask him.

“It isn’t rape,” he says. “Stop saying that. You’re a fool to call it that. Since we’re betrothed, it cannot be rape. As my wife you cannot refuse me. I have a right to you, as your betrothed husband. From now, till your death, you will never be able to refuse me. There can be no rape between us, only my rights and your duty.”

He looks at me and watches the protest die on my lips.

“Your side lost at Bosworth,” he reminds me. “You are the spoils of war.”

COLDHARBOUR PALACE, LONDON, CHRISTMAS FEAST, 1485

I sweep her a curtsey; behind me I see my mother’s carefully judged sinking down and rising up again. We have practiced this most difficult movement in my mother’s rooms, trying to determine the exact level of deference. My mother has a steely dislike for Lady Margaret now, and I will never forgive her for telling her son to rape me before our wedding. Only Cecily and Anne curtsey with uncomplicated deference, as a pair of minor princesses to the king’s all-powerful mother. Cecily even rises with an ingratiating smile, since she is Lady Margaret’s goddaughter and counting on this most powerful woman’s goodwill to make sure that her wedding goes ahead. My sister does not know, and I will never tell her, that they would have taken her, as coldly as they took me, if I had failed to conceive, and she would have been raped in my place while this flint-faced woman prayed for a baby.

“You are welcome to Coldharbour,” Lady Margaret says, and I think it is well named, for it is a most miserable and unfriendly haven. “And to our capital city,” she goes on, as if we girls had not been brought up here in London while she was stuck with a small and unimportant husband in the country, her son an exile and her house utterly defeated.

My mother looks around the rooms, and notes the second-rate cloth cushions on the plain window seat, and that the best tapestry has been replaced by an inferior copy. Lady Margaret Beaufort is a most careful housekeeper, not to say mean.

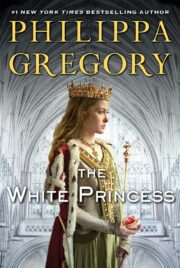

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.