“No one has ever done such a thing before,” I remark. “Even the York and Lancaster kings accepted that it was a rivalry between two houses and that a man might choose one side or the other with honor. What you have done is to name men who have done nothing worse than suffer as traitors. You make them traitors for doing nothing worse than losing. You are saying that whoever wins is in the right.”

“It looks harsh,” he concedes.

“It looks like double-dealing. How can they be named traitors when they were defending the ordained king against an invasion? It’s contrary to the law, and common sense. It must be against God’s will too.”

He smiles as if nothing matters more than that the Tudor reign is established, without question. “Oh no, it’s certainly not against the will of God. My mother is a most holy woman, and she doesn’t think so.”

“And is she to be the only judge?” I ask sharply. “Of God’s will? Of the law in England?”

“Certainly, hers is the only judgment I trust,” he replies. He smiles. “Certainly I would take her advice before yours.”

He takes a glass of wine and then he beckons me to the bed with a cheerful briskness that I begin to think hides his own discomfort at what he is doing. I lie on my back as still as a stone. I never remove my gown, I never even help him when he pulls it up out of his way. I allow him to take me without a word of protest, and I turn my face to the wall so that the first time, the very first time, that he leans down to kiss my cheek, it falls on my ear, and I ignore it as if it were the brush of a buzzing fly.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, THE DAYS OF CHRISTMAS, 1485

“I have missed my course,” I say flatly. “I suppose that’s a sign.”

The delight in her face is answer enough. “Oh! My dear!”

“He has to marry me at once, I won’t be publicly shamed by them.”

“He’ll have no reason to delay. This is what they wanted. Fancy you being so fertile! But I was just the same and my mother was too. We are women blessed with children.”

“Yes,” I say. I can’t put any joy in my voice. “I don’t feel blessed. It’s not as if this is a baby conceived in love. Not even in wedlock.”

She ignores the bleakness in my voice, and the strain in my pale face. She draws me to her and puts her hand on my belly, which is as slim and flat as ever. “It is a blessing,” she assures me. “A new baby, perhaps a boy, perhaps a prince. It doesn’t matter that he was conceived under duress; what matters is that he grows strong and tall and that we make him our own, a rose of York on the throne of England.”

I stand quietly under her touch, like an obedient brood mare, and I know that she is right. “Will you tell him or shall I?”

At once she is planning: “You tell him,” she says. “He will be happy hearing it from you. It will be the first good news that you can bring him.” She smiles at me. “The first of many, I hope.”

I can’t smile back. “I suppose so.”

That evening he comes early, and I serve him his wine and put up my hand to him in refusal as he goes to lead me to the bed.

“I have missed my course,” I say quietly. “I may be with child.”

There is no mistaking the joy in his face. His color flushes up, he takes my hands and draws me closer to him, almost as if he would wrap his arms around me, almost as if he wants to hold me with love. “Oh, I am glad,” he says. “Very glad. Thank you for telling me, it makes my heart lighter. God bless you, Elizabeth. God bless you and the child you carry. This is great news. This is the best news.” He takes a turn to the fire and comes back to me again. “This is such good news! And you so beautiful! And so fertile!”

I nod, my face like stone.

“And d’you know if it will be a boy?” he asks.

“It is too early to know anything,” I say. “And a woman can miss her course from unhappiness or shock.”

“Then I hope you are not unhappy or shocked,” he says cheerfully, as if he wants to forget that I am heartbroken and raped. “And I hope that you have a Tudor boy in there.” He pats my belly as if we were married already, a proprietorial touch. “This means everything,” he says. “Have you told your mother?”

I shake my head, taking a small defiant pleasure in lying to him. “I saved the happy news for you first.”

“I’ll tell my mother when I get home tonight.” He is quite deaf to my grim tone. “There’s nothing I could say that would be better. She’ll turn out the priest for a Te Deum.”

“You’ll be late home,” I say. “It’s after midnight now.”

“She waits up for me,” he says. “She never sleeps before I get in.”

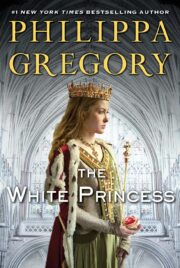

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.