“He loves me!”

“As he tells each and every one.”

“He does. He is coming back to me—”

“As he always promises.”

Furious, I thrust my left fist towards him and he ducks away, expecting a punch in the face. Then he sees the gleam of gold on my finger and he all but laughs. “He gave you this? A ring? I am supposed to be impressed by a love token?”

“It is not a love token, it is a wedding ring. A proper ring given in marriage. We are married.” I make my announcement in triumph, but I am instantly disappointed.

“Dear God, he has fooled you,” he says, anguished. He takes me into his arms and presses my head against his chest. “My poor sister, my poor fool.”

I struggle free. “Let me go, I am nobody’s fool. What are you saying?”

He looks at me with sorrow, but his mouth is twisted into a bitter smile. “Let me guess, was this a secret wedding, in a private chapel? Did none of his friends and courtiers attend? Is Lord Warwick not to be told? Is it to be kept private? Are you to deny it, if asked?”

“Yes. But—”

“You are not married, Elizabeth. You have been tricked. It was a pretend service that has no weight in the eyes of God nor of man. He has fooled you with a trumpery ring and a pretend priest so that he could get you into bed.”

“No.”

“This is the man who hopes to be King of England. He has to marry a princess. He’s not going to marry some beggarly widow from the camp of his enemy, who stood out on the road to plead with him to restore her dowry. If he marries an Englishwoman at all, she will be one of the great ladies of the Lancaster court, probably Warwick’s daughter Isabel. He’s not going to marry a girl whose own father fought against him. He’s more likely to marry a great princess of Europe, an infanta from Spain, or a princesse from France. He has to marry to set himself more safely on the throne, to make alliances. He’s not going to marry a pretty face for love. Lord Warwick would never allow it. And he is not such a fool as to go against his own interests.”

“He doesn’t have to do what Lord Warwick wants! He’s the king.”

“He is Warwick’s puppet,” my brother says cruelly. “Lord Warwick decided to back him, just as Warwick’s father backed Edward’s father. Without the support of Warwick, neither your lover nor his father would have been able to make anything of his claim to the throne. Warwick is the kingmaker, and he has made your lover into King of England. Be very sure he will make the queen too. He will choose who Edward is to marry, and Edward will marry her.”

I am stunned into silence. “But he didn’t. He can’t. Edward married me.”

“A play, a charade, mumming, nothing more.”

“It wasn’t. There were witnesses.”

“Who?”

“Mother, for one,” I say eventually.

“Our mother?”

“She was witness, along with Catherine, her lady-in-waiting.”

“Does Father know? Was he there?”

I shake my head.

“There you are then,” he says. “Who are your many witnesses?”

“Mother, Catherine, the priest, and a boy singer,” I say.

“Which priest?”

“One I don’t know. The king commanded him there.”

He shrugs. “If he was a priest at all. He is more likely some fool or mummer pretending as a favor. Even if he is ordained, the king can still deny that the marriage was valid and it is the word of three women and a boy against the King of England. Easy enough to get you three arrested on some charge and held for a year or so until he is married to whatever princess he chooses. He has played you and Mother for fools.”

“I swear to you that he loves me.”

“Maybe he does,” he concedes. “As maybe he loves each and every one of the women he has bedded, and there are hundreds of them. But when the battle is over and he is riding home and sees another pretty girl by the roadside? He will forget you within a sennight.”

I rub my hand against my cheek and find that my cheeks are wet with tears. “I’m going to tell Mother what you said,” I say weakly. It is the threat of our childhood; it didn’t frighten him then.

“Let’s both go to her. She won’t be happy when she realizes that she has been fooled into pushing her daughter into dishonor.”

We walk in silence through the woods and then over the footbridge. As we go by the big ash tree I glance at the trunk. The looped thread has gone; there is no proof that the magic was ever there. The waters of the river where I dragged my ring from the flood have closed over. There is no proof that the magic ever worked. There is no proof that there is such a thing as magic at all. All I have is a little gold ring shaped like a crown that may mean nothing.

Mother is in the herb garden at the side of the house and, when she sees my brother and me walking together in stubborn silence, a pace apart, saying nothing, she straightens up with the herbs in her basket and waits for us to come towards her, readying herself for trouble.

“Son,” she greets my brother. Anthony kneels for her blessing and she puts her hand on his fair head and smiles down on him. He rises to his feet and takes her hand in his.

“I think the king has lied to you and to my sister,” he says bluntly. “The marriage ceremony was so secret that there is nobody of any authority to prove it. I think he went through the sham ceremony to have the bedding of her, and he will deny that they were married.”

“Oh, do you?” she says, unruffled.

“I do,” he says. “And it won’t be the first time he has pretended marriage to a lady in order to bed her. He has played this game before, and the woman ended with a bastard and no wedding ring.”

My mother, magnificently, shrugs her shoulders. “What he has done in the past is his own affair,” she says. “But I saw him wedded and bedded, and I wager that he will come back to claim her as his wife.”

“Never,” Anthony says simply. “And she will be ruined. If she is with child, she will be utterly disgraced.”

My mother smiles up at his cross face. “If you were right and he was going to deny the marriage, then her prospects would be poor indeed,” she agrees.

I turn my head from them. It is only a moment since my lover was telling me how to keep his son safe. Now this same child is described as my ruin.

“I am going to see my sons,” I say coldly to them both. “I won’t hear this and I won’t speak of it. I am true to him and he will be true to me, and you will be sorry that you doubted us.”

“You are a fool,” my brother says, unimpressed. “I am sorry for that, at least.” And to my mother he says, “You have taken a great gamble with her, a brilliant gamble; but you have staked her life and happiness on the word of a known liar.”

“Perhaps,” my mother says, unmoved. “And you are a wise man, my son, a philosopher. But some things I know better than you, even now.”

I stalk away. Neither of them calls me back.

I have to wait, the whole kingdom has to wait again to hear who to hail as king, who shall command. My brother Anthony sends a man north, scouting for news, and then we all wait for him to come back to tell us if the battle has been joined, and if King Edward’s luck has held. Finally, in May, Anthony’s servant comes home and says he has been in the far north, near to Hexham, and met a man who told him all about it. A bad battle, a bloody battle. I hesitate in the doorway; I want to know the outcome, not the details. I don’t have to see a battle to imagine it anymore; we have become a country accustomed to tales of the battlefield. Everyone has heard of the armies drawn up in their positions, or seen the charge, the falling back and the exhausted pause while they regroup. Or everyone knows someone who has been in a town where the victorious soldiers came through determined to carouse and rob and rape; everyone has stories of women running to a church for sanctuary, screaming for help. Everyone knows that these wars have torn our country apart, have destroyed our prosperity, our friendliness between neighbors, our trust of strangers, the love between brothers, the safety of our roads, the affection for our king; and yet nothing seems to stop the battles. We go on and on seeking a final victory and a triumphant king who will bring peace; but victory never comes and peace never comes and the kingship is never settled.

Anthony’s messenger gets to the point. King Edward’s army has won, and won decisively. The Lancaster forces were routed and King Henry, the poor wandering lost King Henry who does not know fully where he is, even when he is in his palace at Westminster, has run away into the moors of Northumberland, a price on his head as if he were an outlaw, without attendants, without friends, without even followers, like a borderer rebel as wild as a chough.

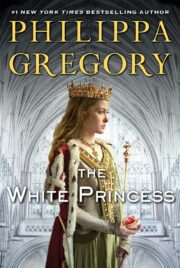

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.