My mother suggests at breakfast that my sisters and I, and the two cousins who are staying with us, might like to watch the army go by, and see our men go off to war.

“Can’t think why,” my father says crossly. “I would have thought you would have seen enough of men going to war.”

“It looks well to show our support,” she says quietly. “If he wins, it will be better for us if he thinks we sent the men willingly. If he loses, no one will remember we watched him go by, and we can deny it.”

“I am paying them, aren’t I? I am arming them with what I have? The arms I have left over from the last time I went out, which, as it happens, was against him? I am rounding them up, and sending them out, and buying boots for those who have none. I would think I was showing support!”

“Then we should do it with a good grace,” my mother says.

He nods. He always gives way to my mother in these matters. She was a duchess, married to the royal Duke of Bedford when my father was nothing but her husband’s squire. She is the daughter of the Count of Saint-Pol, of the royal family of Burgundy, and she is a courtier without equal.

“I would like you to come with us,” she goes on. “And we could perhaps find a purse of gold from the treasure room, for His Grace.”

“A purse of gold! A purse of gold! To wage war on King Henry? Are we Yorkists now?”

She waits till his outrage has subsided. “To show our loyalty,” she says. “If he defeats King Henry and comes back to London victorious, then it will be his court, and his royal favors that are the source of all wealth and all opportunity. It will be he who distributes the land and the patronage and he who allows marriages. And we have a large family, with many girls, Sir Richard.”

For a moment we all freeze with our heads down, expecting one of my father’s thunderous outbursts. Then, unwillingly, he laughs. “God bless you, my spellbinder,” he says. “You are right, as you are always right. I will do as you say, though it goes against the grain, and you can tell the girls to wear white roses, if they can get any this early.”

She leans over to him and kisses him on the cheek. “The dog roses are in bud in the hedgerow,” she says. “It’s not as good as full bloom, but he will know what we mean, and that is all that matters.”

Of course, for the rest of the day, my sisters and cousins are in a frenzy, trying on clothes, washing their hair, exchanging ribbons, and rehearsing their curtseys. Anthony’s wife Elizabeth and two of our quieter companions say that they won’t come, but all my sisters are beside themselves with excitement. The king and most of the lords of his court will go by. What an opportunity to make an impression on the men who will be the new masters of the country! If they win.

“What will you wear?” Margaret asks me, seeing me aloof from the excitement.

“I shall wear my gray gown, and my gray veil.”

“That’s not your best; it’s only what you wear on Sundays. Why wouldn’t you wear your blue?”

I shrug. “I am going since Mother wants us to go,” I say. “I don’t expect anyone to look twice at us.” I take the dress from the cupboard and shake it out. It is slim cut with a little half train at the back. I wear it with a girdle of gray falling low over my waist. I don’t say anything to Margaret, but I know it is a better fit than my blue gown.

“When the king himself came to dinner at your invitation?” she exclaims. “Why wouldn’t he look twice at you? He looked well enough the first time. He must like you—he gave your land back; he came to dinner. He walked in the garden with you. Why wouldn’t he come to the house again? Why wouldn’t he favor you?”

“Because between then and now, I got what I wanted and he did not,” I say crudely, tossing the dress aside. “And it turns out he is not as generous a king as those in the ballads. The price for his kindness was high, too high for me.”

“He never wanted to have you?” she whispers, appalled.

“Exactly.”

“Oh my God, Elizabeth. What did you say? What did you do?”

“I said no. But it was not easy.”

She is deliciously scandalized. “Did he try to force you?”

“Not much, it doesn’t matter,” I mumble. “And it’s not as if I was anything to him but a girl on the roadside.”

“Perhaps you shouldn’t come tomorrow,” she suggests. “If he offended you. You can tell Mother that you’re ill. I’ll tell her, if you like.”

“Oh, I’ll come,” I say, as if I don’t care either way.

In the morning I am not so brave. A sleepless night and a piece of bread and beef for breakfast does not help my looks. I am pale as marble, and though Margaret rubs red ochre into my lips, I still look drawn, a ghostly beauty. Among my brightly dressed sisters and my cousins, I, in my gray gown and headdress, stand out like a novice in a nunnery. But when my mother sees me, she nods, pleased. “You look like a lady,” she says. “Not like some peasant girl tricked out in her best to go to a fair.”

As a reproof this is not successful. The girls are so delighted to be allowed to the muster at all that they don’t in the least mind being reproached for looking too bright. We walk together down the road to Grafton and see before us, at the side of the highway, a straggle of a dozen men armed with staves, one or two with cudgels: Father’s recruits. He has given them all a badge of a white rose and reminded them that they are now to fight for the House of York. They used to be foot soldiers for Lancaster; they must remember that they are now turncoats. Of course, they are indifferent to the change of loyalty. They are fighting as he bids them for he is their landlord, the owner of their fields, their cottages, almost everything they see around them. His is the mill where they grind their corn, the ale house where they drink pays rent to him. Some of them have never been beyond the lands he owns. They can hardly imagine a world in which “squire” does not simply mean Sir Richard Woodville, or his son after him. When he was Lancaster, so were they. Then he was given the title Rivers, but they were still his and he theirs. Now he sends them out to fight for York, and they will do their best, as always. They have been promised payment for fighting and that their widows and children will be cared for if they fall. That is all they need to know. It does not make them an inspired army, but they raise a ragged cheer for my father and pull off their hats with appreciative smiles for my sisters and me, and their wives and children bob curtseys as we come towards them.

There is a burst of trumpets, and every head turns towards the noise. Around the corner, at a steady trot, come the king’s colors and trumpeters, behind them the heralds, behind them the yeomen of his household, and in the middle of all this bellow and waving pennants, there he is.

For a moment I feel as if I will faint, but my mother’s hand is firm under my arm, and I steady myself. He raises his hand in the signal for halt, and the cavalcade comes to a standstill. Following the first horses and riders is a long tail of men at arms; behind them, other new recruits, looking sheepish like our men, and then a train of wagons with food, supplies, weapons, a great gun carriage drawn by four massive shire horses, and a trail of ponies and women, camp followers and vagrants. It is like a small town on the move: a small deadly town, on the move to do harm.

King Edward swings down from his horse and goes to my father, who bows low. “All we could muster, I am afraid, Your Grace. But sworn to your service,” my father says. “And this, to help your cause.”

My mother steps forward and offers the purse of gold. King Edward takes it and weighs it in his hand and then kisses her heartily on both cheeks. “You are generous,” he says. “And I will not forget your support.”

His gaze goes past her to me, where I stand with my sisters, and we all curtsey together. When I come up, he is still looking at me, and there is a moment when all the noise of the army and the horses and the men falling in freezes into silence, and it is as if there is only he and I alone, in the whole world. Without thinking what I am doing, as if he has wordlessly called me, I take a step towards him, and then another, until I have walked past my father and mother and am face-to-face with him, so close that he might kiss me, if he wished.

“I can’t sleep,” he says so quietly that only I can hear. “I can’t sleep. I can’t sleep. I can’t sleep.”

“Nor I.”

“You neither?”

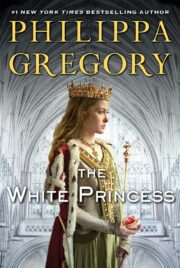

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.