She nods. “They know not to come down.”

And so I walk down the stairs, my head steady as if wearing a crown instead of the heavy hood, my green gown brushing aside the scented rushes, as they throw open the double doors and Henry Tudor, the conqueror of England, newly crowned king, the murderer of my happiness, walks into the great hall below me.

My first thought is relief; he is less of a man than I expected. All these years of knowing that there was a pretender to the throne waiting for his chance to invade turned him into a thing of terror, a beast, larger than life. They said that he was guarded by a giant of a man at Bosworth, and I had imagined him as a giant also. But the man who comes into the hall is slight of build, tall but spare, a man of nearly thirty, energy in his walk but strain in his face, brown hair, and narrow brown eyes. For the first time it strikes me that it must be hard to spend your life in exile and finally win your kingdom by a thread, by the action of a turncoat in battle, and to know that most of the country does not celebrate your luck, and the woman that you have to marry is in love with someone else: your dead enemy and the rightful king. I have been thinking of him as triumphant; but here I see a man burdened by an odd twist of fate, coming to victory by a sneaking disloyalty, on a hot day in August, uncertain even now, if God is with him.

I pause on the stairs, my hands on the cold marble balustrade, leaning over to look down on him. His reddish-brown hair is thinning slightly on the top of his head; I can see it from my vantage point as he takes off his hat and bows low over my mother’s hand, and he comes up and smiles at her without warmth. His face is guarded, which is understandable, as he is coming to the home of a most unreliable ally. Sometimes my Lady Mother was supporting his plan against Richard, and sometimes she was against him. She sent her own son Thomas Grey to his court as his supporter but then called him home again, suspecting Henry of killing our prince. I imagine he never knew whether she was friend or enemy; of course he mistrusts her. He must mistrust all of us duplicitous princesses. He must fear my dishonesty, my infidelity, worst of all.

He kisses my mother’s fingertips as lightly as he can, as if he expects nothing but sham appearances from her, perhaps from everyone. Then he straightens up and follows her upward glance, and sees me, standing above him, on the stairs.

He knows at once who I am, and my nod of acknowledgment tells him that I recognize in him the man that I am to marry. We look more like two strangers agreeing to undertake an uncomfortable expedition together than lovers greeting. Until four months ago I was the lover of his enemy and praying three times daily for Tudor’s defeat. As recently as yesterday he was taking advice to see if he could avoid his betrothal to me. Last night, I was dreaming that he did not exist and woke wishing that it was the day before Bosworth and that he would invade only to face defeat and death. But he won at Bosworth, and now he cannot escape from his oath to marry me and I cannot escape from my mother’s promise that I shall marry him.

I come slowly down the stairs as we take the measure of each other, as if to see the truth of a long-imagined enemy. It is extraordinary to me to think that whether I like it or not, I shall have to marry him, bed him, bear his children, and live with him for the rest of my life. I shall call him husband, he will be my master, I will be his wife and his chattel. I will never escape his power over me until his death. Coldly, I wonder if I will spend the rest of my life, daily wishing for his death.

“Good day, Your Grace,” I say quietly, and I come down the last steps and curtsey and give him my hand.

He bows to kiss my fingers, and then draws me to him and kisses me on one cheek and then another, like a French courtier, pretty manners that mean nothing. His scent is clean, pleasant, I can smell the fresh winter countryside in his hair. He steps back, and I see his brown guarded eyes, and his tentative smile.

“Good day, Princess Elizabeth,” he says. “I am glad to meet you at last.”

“You will take a glass of wine?” my mother offers.

“Thank you,” he says; but he does not shift his gaze from my face, as if he is judging me.

“This way,” my mother says equably and leads the way to a private chamber off the great hall, where there is a decanter of Venetian glass and matching wine goblets for the three of us. The king seats himself on a chair but rudely gives no permission to us, and so we have to remain standing before him. My mother pours the wine and serves him first. He raises a glass to me and drinks as if he were in a taproom, but does not make a toast. He seems content to sit in silence, thoughtfully regarding me as I stand like a child before him.

“My other daughters.” My mother introduces them serenely. It takes an awful lot to shake my mother—this is a woman who has slept through a regicide—and she nods to the doorway. Cecily and Anne come in with Bridget and Catherine behind them. They all four curtsey very low. I can’t stop myself smiling at Bridget’s dignified sinking and rising. She is only a little girl, but she is no less than a duchess already in her grand manners. She looks at me reprovingly; she is a most serious five-year-old.

“I am glad to meet you all,” the new king says generally, not bothering to get to his feet. “And you are comfortable here? You have everything you need?”

“I thank you, yes,” my mother says, as if she did not once own all of England, and this was her favorite palace and run exactly as she commanded.

“Your allowance will be paid every quarter,” he says to her. “My Lady Mother is making the arrangements.”

“Please give my best wishes to Lady Margaret,” my mother says. “Her friendship has sustained me recently, and her service was very dear to me in the past.”

“Ah,” he says, as if he doesn’t much relish being reminded that his mother was my mother’s lady-in-waiting. “And your son Thomas Grey will be released from France and can come home to you,” he goes on, dispensing his goods.

“I thank you. And please tell your mother that Cecily, her goddaughter, is well,” my mother pursues. “And grateful to you and your mother for your care of her forthcoming marriage.” Cecily drops a little extra curtsey to demonstrate to the king which one of us she is, and he gives a bored nod. She looks up as if she longs to remind him that she is only waiting for him to name her wedding day, and until he does so she is still neither widow nor maid. But he gives her no opportunity to speak.

“My advisors inform me that the people are eager to see Princess Elizabeth married,” he says.

My mother inclines her head.

“I wanted to assure myself that you are well and happy,” he says directly to me. “And that you consent.”

Startled, I look up. I am not well, and I am far from happy; I am deep in grief for the man I love, the man killed by this new king and buried without honor. This man sitting before me now, asking so courteously that I consent, allowed his men to strip Richard of his armor, and then of his linen, and tie his naked body across the saddle of his horse and trot it home. They told me that they let Richard’s dead lolling head knock, in passing, against the wooden beam of the Bow Bridge as they brought him in to Leicester. That clunk, the noise of dead skull against post, sounds through my days, echoes in my dreams. Then they exposed his naked broken body on the chancel steps of the church so that everyone knew he was completely and utterly dead, and that any chance of England’s happiness under the House of York was completely and utterly over.

“My daughter is well and happy, and is your most obedient servant,” my mother says pleasantly, in the little silence.

“And what motto shall you choose?” he asks. “When you are my wife?”

I begin to wonder if he has come only to torment me. I have not thought of this. Why on earth would I have thought of my wifely motto? “Oh, do you have a preference?” I ask him, my voice coldly uninterested. “For I have none.”

“My Lady Mother suggested ‘humble and penitent,’ ” he says.

Cecily snorts with laughter, turns it into a cough, and looks away, blushing. My mother and I exchange one horrified glance, but we both know we can say nothing.

“As you wish.” I manage to sound indifferent, and I am glad of this. If nothing else, I can pretend that I don’t care.

“Humble and penitent, then,” he says, quietly to himself, as if he is pleased, and now I am sure that he is laughing at us.

Next day my mother comes to me, smiling. “Now I understand why we were honored with a royal visit yesterday,” she says. “The speaker of the House of Parliament himself stepped down from his chair and begged the king, in the name of the whole house, to marry you. The commons and the lords told him that they must have the issue resolved. The people will not stand for him as king without you at his side. They put such a petition to him that he could not deny them. They promised me this, but I wasn’t sure they would dare to go through with it. Everyone is so afraid of him; but they want a York girl on the throne and the Cousins’ War concluded by a marriage of the cousins more than anything in the world. Nobody can feel certain that peace has come with Henry Tudor unless you’re on the throne too. They don’t see him as anything more than a lucky pretender. They told him they want him to be a king grafted onto the Plantagenets, this sturdy vine.”

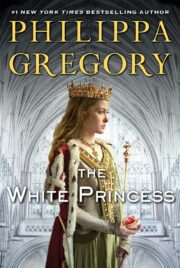

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.