As slowly as I can, I let my eyes rise to his face. My gaze lingers on his mouth, then I look up.

“Dear God, I have to have you,” he breathes.

“I cannot be your mistress,” I say simply. “I would rather die than dishonor my name. I cannot bring that shame on my family.” I pause. I am anxious not to be too discouraging. “Whatever I might wish in my heart,” I say very softly.

“But you do want me?” he asks boyishly, and I let him see the warmth in my face.

“Ah,” I say. “I should not tell you . . .”

He waits.

“I should not tell you how much.”

I see, swiftly hidden, the gleam of triumph. He thinks he will have me.

“Then you will come?”

“No.”

“Then must I go? Must I leave you? May I not . . .” He leans his face towards me and I raise mine. His kiss is as gentle as the brush of a feather on my soft mouth. My lips part slightly and I can feel him tremble like a horse held on a tight rein. “Lady Elizabeth . . . I swear it . . . I have to . . .”

I take a step back in this delicious dance. “If only . . .” I say.

“I’ll come tomorrow,” he says abruptly. “In the evening. At sunset. Will you meet me where I first saw you? Under the oak tree? Will you meet me there? I would say good-bye before I go north. I have to see you again, Elizabeth. If nothing more. I have to.”

I nod in silence and watch him turn on his heel and stride back to the house. I see him go round to the stable yard and then moments later his horse thunders down the track with his two pages spurring their horses to keep pace with him. I watch him out of sight, and then I cross the little footbridge over the river and find the thread around the ash tree. Thoughtfully, I wind in the thread by another length and I tie it up. Then I walk home.

At dinner the next day there is something of a family conference. The king has sent a letter to say that his friend Sir William Hastings will support my claim to my house and land at Bradgate, and I can be assured that I will be restored to my fortune. My father is pleased; but all my brothers—Anthony, John, Richard, Edward, and Lionel—are united in suspicion of the king, with the alert pride of boys.

“He is a notorious lecher. He is bound to demand to meet her; he is bound to summon her to court,” John pronounces.

“He did not return her lands for charity. He will want payment,” Richard agrees. “There is not a woman at court whom he has not bedded. Why would he not try for Elizabeth?”

“A Lancastrian,” says Edward, as if that is enough to ensure our enmity, and Lionel nods sagely.

“A hard man to refuse,” Anthony says thoughtfully. He is far more worldly than John; he has traveled all around Christendom and studied with great thinkers, and my parents always listen to him. “I would think, Elizabeth, that you might feel compromised. I would fear that you would feel under obligation to him.”

I shrug. “Not at all. I have nothing more but my own again. I asked the king for justice and I received it as I should, as any supplicant should, with right on their side.”

“Nonetheless, if he sends, you will not go to court,” my father says. “This is a man who has worked his way through half the wives of London and is now working his way through the Lancastrian ladies too. This is not a holy man like the blessed King Henry.”

Nor soft in the head like blessed King Henry, I think, but aloud I say, “Of course, Father, whatever you command.”

He looks sharply at me, suspicious of this easy obedience. “You don’t think you owe him your favor? Your smiles? Worse?”

I shrug. “I asked him for a king’s justice, not for a favor,” I say. “I am not a manservant whose service can be bought or a peasant who can be sworn to be a liege man. I am a lady of good family. I have my own loyalties and obligations that I consider and honor. They are not his. They are not at the beck and call of any man.”

My mother drops her head to hide her smile. She is the daughter of Burgundy, the descendant of Melusina the water goddess. She has never thought herself obliged to do anything in her life; she would never think that her daughter was obliged to anything.

My father glances from her to me and shrugs his shoulders as if to concede the inveterate independence of willful women. He nods to my brother John and says, “I am riding over to Old Stratford village. Will you come with me?” And the two of them leave together.

“You want to go to court? Do you admire him? Despite everything?” Anthony asks me quietly as my other brothers scatter from the room.

“He is King of England,” I say. “Of course I will go if he invites me. What else?”

“Perhaps because Father just said you were not to go, and I advised you against it.”

I shrug. “So I heard.”

“How else can a poor widow make her way in a wicked world?” he teases me.

“Indeed.”

“You would be a fool to sell yourself cheap,” he warns me.

I look at him from under my eyelashes. “I don’t propose to sell myself at all,” I say. “I am not a yard of ribbon. I am not a leg of ham. I am not for sale to anyone.”

At sunset I am waiting for him under the oak tree, hidden in the green shadows. I am relieved to hear the sound of only one horse on the road. If he had come with a guard, I would have slipped back to my home, fearing for my own safety. However tender he may be in the confines of my father’s garden, I don’t forget that he is the so-called king of the Yorkist army and that they rape women and murder their husbands as a matter of course. He will have hardened himself to seeing things that no one should witness; he will have done things himself which are the darkest of sins. I cannot trust him. However heart-stopping his smile and however honest his eyes, however much I think of him as a boy fired to greatness by his own ambition, I cannot trust him. These are not chivalrous times; these are not the times of knights in the dark forest and beautiful ladies in moonlit fountains and promises of love that will be ballads, sung forever.

But he looks like a knight in a dark forest when he pulls up his horse and jumps down in one easy movement. “You came!” he says.

“I cannot stay long.”

“I am so glad you came at all.” He laughs at himself almost in bewilderment. “I have been like a boy today—couldn’t sleep last night for thinking of you, and all day I have wondered if you would come at all, and then you came!”

He loops the reins of his horse over a branch of the tree and slides his hand around my waist. “Sweet lady,” he says into my ear. “Be kind to me. Will you take off your headdress and let down your hair?”

It is the last thing I thought he would demand of me, and I am shocked into instant consent. My hand goes to my headdress ribbons at once.

“I know. I know. I think you are driving me mad. All I have been able to think about all day is whether you would let me take down your hair.”

In answer I untie the tight bindings of my tall conical headdress and lift it off. I put it carefully on the ground and turn to him. Gently as any maid-in-waiting, he puts his hand to my head and pulls out the ivory pins, tucking each into the pocket of his doublet. I can feel the silky kiss of my thick hair tumbling down as the fair cascade of it falls over my face. I shake my head and toss it back like a thick golden mane, and I hear his groan of desire.

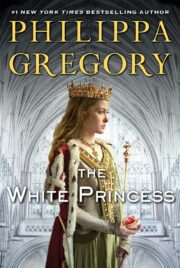

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.