The other men charged with treason in the last plot for the York prince are all hanged or fined or banished. Occasional pardons are issued in the king’s name, with his initial weakly scrawled at the foot of the page. Nobody knows if he has locked himself up, sick with remorse, or if he is just too tired to go on fighting. The plot is over, but still the king does not come out of his chamber; he reads nothing and will see no one. The court and the kingdom wait for him to return.

I go to visit My Lady the King’s Mother and find her with all the business of the throne on the table before her, as if she were regent. “I have come to ask you if the king is very ill,” I say. “There is much gossip, and I am concerned. He will not see me.”

She looks at me and I see that the papers are shuffled into piles, but she is not reading them, she is signing nothing. She is at a loss. “It’s grief,” she says simply. “It is grief. He is sick with grief.”

I rest my hand on my heart and feel it thud with anger. “Why? Why should he grieve? What has he lost?” I ask, thinking of Margaret and her brother, Lady Katherine and her husband, of my sisters and myself, who go through our days and show the world nothing but indifference.

She shakes her head as if she cannot understand it herself. “He says he has lost his innocence.”

“Henry, innocent?” I exclaim. “He entered his throne through the death of a king! He came into the kingdom as a pretender to the throne!”

“Don’t you dare say it!” She rounds on me. “Don’t you say such a thing! You of all people!”

“But I don’t understand what you mean,” I explain. “I don’t understand what he is saying. He has lost his innocence? When was he innocent?”

“He was a young man, he spent his life aspiring to the throne,” she says, as if the words are forced from her, as if it is a hard confession, choked out of her. “I raised him to be like this, I taught him myself that he must be King of England, that there was nothing else for him but the crown. It was my doing. I said that he should think of nothing but returning to England and claiming his own and holding it.”

I wait.

“I told him it was God’s will.”

I nod.

“And now he has won it,” she says. “He is where he was born to be. But to hold it, to be sure of it, he has had to kill a young man, a young man just like him, a boy who aspired to the throne, who was also raised to believe it was his by right. He feels as if he has killed himself. He has killed the boy that he was.”

“The boy that he was,” I repeat slowly. She is showing me a boy I had not seen before. The boy who was named for the Tournai boatman was also the boy who said he was a prince, but to Henry he was a fellow-pretender, someone raised and trained for only one destiny.

“That was why he liked the boy so much. He wanted to spare him, he was glad to bind himself to forgive him. He hoped to make him look like a nothing, keeping him at court like a Fool, paying for his clothes from the same purse as he paid for his Fool and his other entertainments. That was part of his plan. But then he found that he liked him so much. Then he found that they were both boys, raised abroad, always thinking of England, always taught of England, always told that the time would come when they must sail for home and enter into their kingdom. He once said to me that nobody could understand the boy but him—and that nobody could understand him but the boy.”

“Then why kill him?” I burst out. “Why would he put him to death? If the boy was him, a looking-glass king?”

She looks as if she is in pain. “For safety,” she said. “While the boy lived they would always be compared, there would always be a looking-glass king, and everyone would always look from one to the other.”

She says nothing for a moment and I think of how Henry always knew that he did not seem like a king, not a king like my father, and how the boy that Henry called Perkin always looked like a prince.

“And besides, he could not be safe until the boy was dead,” she says. “Even though he tried to keep him close. Even when the boy was in the Tower, enmeshed in lies, entrapped with his own words, there were people all over the country pledging themselves to save him. We hold England now; but Henry feels that we will never keep it. The boy is not like Henry. He had that gift—the gift of being beloved.”

“And now you will never be safe.” I repeat her words to her and I know that my revenge on them is here, in what I am saying to the woman who has taken my place in the queen’s rooms, behind this table, just as her son took the place of my brother. “You don’t have England,” I tell her. “You don’t have England, and you will never be safe, and you will never be beloved.”

She bows her head as if it is a life sentence, as if she deserves it.

“I shall see him,” I say, going to the door that adjoins his set of rooms, the queen’s doorway.

“You can’t go in.” She steps forwards. “He’s too ill to see you.”

I walk towards her as if I would stride right through her. “I am his wife,” I say levelly. “I am Queen of England. I will see my husband. And you shall not stop me.”

For a moment I think I will have to physically push her aside, but at the last moment she sees the determination in my face and she falls back and lets me open the door and go in.

He is not in the antechamber, but the door to his bedroom is open and I tap on it lightly, and step into his room. He is at the window, the shutters open so that he can see the night sky, looking out, though there is nothing but darkness outside and the glimmering of a scatter of stars like spilled sequins across the sky. He glances round as he sees me come in, but he does not speak. Almost I can feel the ache in his heart, his loneliness, his terrible despair.

“You’ve got to come back to court,” I say flatly. “People will talk. You cannot stay hiding in here.”

“You call it hiding?” he challenges.

“I do,” I say without hesitation.

“They are missing me so much?” he asks scathingly. “They love me so much? They long to see me?”

“They expect to see you,” I say. “You are the King of England, you have to be seen on your throne. I cannot carry the burden of the Tudor crown alone.”

“I didn’t think it would be so hard,” he says, almost an aside.

“No,” I agree. “I didn’t think it would be so hard either.”

He rests his head against the stone window arch. “I thought once the battle was won, it would be easy. I thought I would have found my heart’s desire. But—d’you know?—it is worse being a king than being a pretender.”

He turns and looks at me for the first time in weeks. “Do you think I have done wrong?” he asks. “Was it a sin to kill the two of them?”

“Yes,” I say simply. “And I am afraid that we will have to pay the price.”

“You think we will see our son die, that our grandson will die and our line end with a Virgin Queen?” he asks bitterly. “Well, I have had a prophecy drawn up, and by a more skilled astrologist than you and your witch mother. They say that we will live long and in triumph. They all tell me that.”

“Of course they do,” I say honestly. “And I don’t pretend to foresee the future. But I do know that there is always a price to be paid.”

“I don’t think our line will die out,” he says, trying to smile. “We have three sons. Three healthy princes: Arthur, Henry, and Edmund. I hear nothing but good of Arthur, Henry is bright and handsome and strong, and Edmund is well and thriving, thank God.”

“My mother had three princes,” I reply. “And she died without an heir.”

He crosses himself. “Dear God, Elizabeth, don’t say such a thing. How can you say such things?”

“Someone killed my brothers,” I say. “They both died without saying good-bye to their mother.”

“They didn’t die at my hand!” he shouts. “I was in exile, miles away. I didn’t order their deaths! You can’t blame me!”

“You benefit from their deaths.” I pursue the argument. “You are their heir. And anyway, you killed Teddy, my cousin. Not even your mother can deny that. An innocent boy. And you killed the boy, the charming boy, for being nothing but beloved.”

He puts one hand over his face and blindly stretches his other hand out to me. “I did, I did, God forgive me. But I didn’t know what else to do. I swear there was nothing else I could do.”

His hand finds mine and he grips it tightly, as if I might haul him out from sorrow. “Do you forgive me? Even if no one else ever does. Can you forgive me? Elizabeth? Elizabeth of York—can you forgive me?”

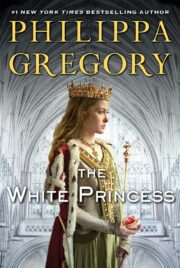

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.