Cecily delights in our sudden restoration to our titles, all of us York princesses are glad to be ourselves once again; but I find my mother walking in silence by the cold river, her hood over her head, her cold hands clasped in her muff, her gray eyes on the gray water. “Lady Mother, what is it?” I go to take her hands and look into her pale face.

“He thinks my boys are dead,” she whispers.

I look down and see the mud on her boots and on the hem of her gown. She has been walking beside the river for an hour at least, whispering to the rippling water.

“Come inside, you’re freezing,” I say.

She lets me take her hand and lead her up the graveled path to the garden door, and help her up the stone stairs to her privy chamber.

“Henry must have certain proof that both my boys are dead.”

I take off her cloak and press her into a chair beside the fire. My sisters are out, walking to the houses of the silk merchants, gold in their purses, servants to carry their purchases home, served on bended knee, laughing at their restoration. Only my mother and I struggle here, locked in grief. I kneel before her and feel the dry rushes under my knees release their cold perfume. I take her icy hands in mine. Our heads are so close together that no one, not even someone listening at the door, could hear our whispered conversation.

“Lady Mother,” I say quietly. “How do you know?”

She bows her head as if she has been struck hard in the heart. “He must do. He must be absolutely sure that they are both dead.”

“Were you still hoping for your son Edward, even now?”

A little gesture, like that of a wounded animal, tells me that she has never stopped hoping that her eldest York son had somehow escaped from the Tower and still lived, somewhere, against the odds.

“Really?”

“I thought I would know,” she says very quietly. “In my heart. I thought that if my boy Edward had been killed I would have known in that moment. I thought that his spirit could not have left this world and not touched me as he went. You know, Elizabeth, I love him so much.”

“But, Mother, we both heard the singing that night, the singing that comes when one of our house is dying.”

She nods. “We did. But still I kept on hoping.”

There is a little silence between us, as we observe the death of her hope.

“D’you think Henry has made a search and found the bodies?”

She shakes her head. She’s certain of this. “No. For if he had the bodies, he would show them to the world and give them a great funeral for everyone to know they’re gone. If he had the bodies, he would give them a royal burial. He’d have us all draped in darkest blue, in mourning for months. If he had any firm evidence, he would use it to blacken Richard’s name. If he had anyone he could accuse of murder, he would put him on trial and publicly hang him. The best thing in the world for Henry would have been to find two bodies. He will have been praying ever since he landed in England that he would find them dead and buried, so that his claim to the throne was secure, so that nobody could ever rise up and impersonate them. The only person in England who wants to know more urgently than me where my sons are tonight is Henry the new king.

“So he can’t have found their bodies, but he must be certain that they are dead. Someone must have promised him that they were killed. Someone that he must trust. Because he would never have restored the royal title to our family if he thought we had a surviving boy. He would never have made you girls princesses of York if he thought that somewhere there was also a living prince.”

“So he’s been assured that both Edward and Richard are dead?”

“He must be sure. Otherwise, he would never have ruled that your father and I were married. The act that makes you a princess of York again makes your brothers princess of York. If our Edward is dead, then your younger brother is King Richard IV of England, and Henry is a usurper. Henry would never have restored a royal title to a live rival. He must be sure that both the boys are dead. Someone must have sworn to him that the murder was truly done. Someone must have told him, without doubt, that they killed two boys and saw them dead.”

“Could it be his mother?” I whisper.

“She’s the only one with reason to kill them, who was here when they disappeared, who is alive now,” my mother says. “Henry was in exile, his uncle Jasper with him. Henry’s ally the Duke of Buckingham might have done it; but he’s dead, so we’ll never know. If someone has reassured Henry, just now, that he is safe, then it must be his mother. The two of them must have convinced themselves that they are safe. They think both York princes are dead. Next, he will propose marriage to you.”

“He has waited till he is certain that my two little brothers are dead before he names me princess and offers me marriage?” I ask. The taste in my mouth is as bitter as my question.

My mother shrugs. “Of course. What else could he do? This is the way of the world.”

My mother is right. Early one wintry evening, a troop of the king’s newly appointed yeomen of the guard, smart in their scarlet livery, march up to the door of Westminster Palace and a herald delivers the message that King Henry will have the pleasure of visiting me within the hour.

“Run,” my mother says, taking in this letter with one swift glance. “Bess!”—to the new maid-in-waiting. “Go with Her Grace and fetch my new headdress, and her new green gown, and tell the boy to bring hot water to her room and the bath at once! Cecily! Anne! You get dressed too, and get your sisters dressed and get the Warwick children to go to the schoolroom and tell their schoolmaster to keep them there until I send for them. The Warwick children are not to come downstairs while the king is here. Make sure they understand that.”

“I’ll wear a hood, my black hood,” I say stubbornly.

“My new headdress!” she exclaims. “My jeweled headdress! You are to be Queen of England, why look like his housekeeper? Why look like his mother? As dull as a nun?”

“Because that’s what he must like,” I say quickly. “Don’t you see? He’ll like girls who are as dull as nuns. He was never at our court, he never saw the fine dresses and the beautiful women. He never saw the dances and the gowns and the glamour of our court. He was stuck like a poor boy in Brittany with maidservants and housekeepers. He lived in one poor inn after another. And then he comes to England and spends all the time with his mother, who dresses like a nun and is as ugly as sin. I have to look modest, not grand.”

My mother snaps her fingers in exasperation at herself. “Fool that I am! Quite right! Right! So go!” She gives me a little push in the back. “Go, and hurry!” I hear her laugh. “Be as plain as you can! If you can manage not to be the most beautiful girl in England, that would be excellent!”

I run as she bids me, and the lad who brings the firewood rolls the great wooden bath into my bedroom and labors up the stairs with the heavy jugs of hot water to hand over at the door. I have to wash in a hurry as the maid brings in the jugs and fills up the bath, and then I dry and twist my damp hair up under my black gable hood, which sits heavily on my forehead, two great wings either side of my ears. I step into my linen and my green gown, and Bess darts around me threading the laces through the holes to fasten the bodice until I am trussed like a chicken, I slip on my shoes and turn to her, and she smiles at me and says: “Beautiful. You are so beautiful, Your Grace.”

I take up the hand mirror and see my face reflected dimly in the beaten silver. I am flushed from the heat of the bath and I look well, my face oval, my eyes deep gray. I try a little smile and see my lips curve upwards, an empty expression without any glimmer of happiness. Richard told me I was the most beautiful girl that had ever been born, that one glance from me set him on fire with desire, that my skin was perfect, that my hair was his delight, that he never slept so well as with his face buried in my blond plait. I don’t expect to hear such words of love ever again. I don’t expect to feel beautiful ever again. They buried my joy and my girl’s vanity with my lover, and I don’t expect to feel either ever again.

The bedroom door bursts open. “He’s here,” Anne says breathlessly. “Riding into the courtyard with about forty men. Mother says come at once.”

“Are the Warwick children upstairs in the schoolroom?”

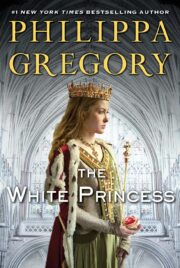

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.