My half brother Thomas Grey tells me that he thinks that Teddy did not know what was going to happen to him. He confesses his little sins and gives a penny to the headsman when they tell him to do so. He was always obedient, always trying to please. He puts his fair York head down on the block and he stretches out his arms in the gesture of assent. But I don’t think he ever knew that he was agreeing to the scything down of the axe and the end of his little life.

Henry will not dine in the great hall of Westminster that night, his mother is at prayer. In their absence, I have to walk in alone, at the head of my ladies, Katherine behind me in deepest black, Margaret wearing a gown of dark blue. The hall is hushed, the people of our own household quiet and surly, as if some joy has been taken from us, and we will never get it back.

There is something different about the hall as I walk through the silent court and when I am seated, and can look around, I see what has changed. It is how they have seated themselves. Every night the men and women of our extensive household come in to dine and sit in order of precedence and importance, men on one side, women on the other of the great hall. Each table seats about twelve diners and they share the common dishes that are placed in the center of the table. But tonight it is different; some tables are overcrowded, some have empty places. I see that they have grouped themselves regardless of tradition or precedent.

Those who befriended the boy, those who were of the House of York, those who served my mother and father or whose fathers served my mother and father, those who love me, those who love my cousin Margaret and remember her brother Teddy—they have chosen to sit together; and there are many, many tables in the great hall where they are seated in utter silence, as if they have sworn a vow never to speak again, and they look around them saying nothing.

The other tables are those that have taken Henry’s side. Many of them are old Lancastrian families, some of them were in his mother’s household or serve her wider family, some came over with him to fight at Bosworth, some, like my half brother Thomas Grey or my brother-in-law Thomas Howard, spend every day of their lives trying to show their loyalty to the new Tudor house. They are trying to appear as usual, leaning across the half-empty tables, talking unnaturally loudly, finding things to say.

Almost without trying to, the court has sorted itself into those who are in mourning tonight, wearing gray or black or navy ribbons pinned to their jerkins or carrying dark gloves, and those who are trying, loudly and cheerfully, to behave as if nothing has happened.

Henry would be horrified if he saw the numbers that are openly mourning for the House of York. But Henry will not see it. Only I know that he is facedown on his bed, his cape hunched over his shoulders, unable to walk to dinner, unable to eat, barely able to breathe in a spasm of guilt and horror at what he has done, which can never be undone.

Outside the storm is still rumbling, the skies are billowing with dark clouds and there is no moon at all. The court is uneasy too; there is no sense of victory, and no sense of closing a chapter. The death of the two young men was supposed to bring a sense of peace. Instead we are all haunted by the sense that we have done something very wrong.

I look across at the table where Henry’s young companions always sit, expecting them at least to be cracking a jest or playing some foolish prank on each other, but they are waiting for dinner to be served in silence, their heads bowed, and when it comes they eat in silence, as if there is nothing to laugh about at the Tudor court anymore.

Then I see something that makes me glance across to the groom of the servery, wondering that he should allow it—certain that he will report it. At the head of the table of the young men, where the boy used to sit, they have put his cup, his knife, his spoon. They have set a plate for him, they have poured wine as if he were coming to dine. In their own way, defiantly, the young men are showing their loyalty to a ghost, a dream; expressing their love for a prince who—if he was ever there at all—is gone now.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, WINTER 1499

But still the king gets no better, and his mother spends all her time in the chapel praying for him, or in his room begging him to sit up, turn his face from the wall, drink a little wine, taste a little meat, eat. The Master of the Revels comes to me to make plans for the Christmas feasts, the dancers must rehearse and the choristers practice new music, but I don’t know if we are going to have a silent court in mourning with an empty throne, and I tell him we can plan nothing until the king is well again.

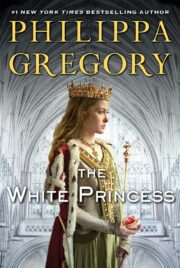

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.