“Richard’s son died, as soon as they named him Prince of Wales,” My Lady reminds her silent son. “It is proof of his guilt.”

He turns and glances at her. “You knew of this curse?”

She blinks like an old reptile, and I know that John Morton reported my words to My Lady as promptly as he prayed to God.

“You did not think you should warn me?” Henry asks.

“Why should anyone warn you?” she asks, knowing that neither of them can answer such a question. “We had nothing to do with their deaths. Richard killed the boys in the Tower,” she asserts steadily. “Or it was Henry Stafford, the Duke of Buckingham. Richard’s line is ended, the young Duke of Buckingham is not strong. If this curse has any power it will fall on him.”

Henry returns his hard gaze to me. “So what is your warning?” he asks me. “What is our danger? What can it possibly be to do with us?”

I slide off my chair and I kneel before him as if he might judge me too. “This boy,” I say, “the one who claims to be Prince Richard of York . . . If we put him to death, that curse might fall on us.”

“Only if he is the prince,” Henry says acutely. “Are you recognizing him? Do you dare to come here and tell me that you recognize him now? After all that we have been through? After claiming to know nothing all the time?”

I shake my head and bow lower. “I don’t recognize him, and I never have. But I want us to take care. I want us to take care for our children. Husband, my lord, we might lose our son in his youth. We might lose a grandson in his youth. Our line might end with a girl and then with nothing. Everything that you have done, everything that we have endured might end with a Virgin Queen, a barren girl, and then . . . nothing.”

Henry does not sleep that night at all, not in my bed nor in his own. He goes to the chapel and he kneels beside his mother on the chancel steps, and the two of them pray, their faces buried in their hands—but nobody knows what they pray for. That is between them and God.

I know they are there, for I am in the royal gallery in the chapel, on my knees, Lady Katherine beside me. Both of us are praying that the king will be merciful, that he will forgive the boy and release him and Teddy, that this reign which began in blood with the sweat might continue with forgiveness. That the long Cousins’ War might end with reconciliation, and not continue to another generation. That the Tudor way might be merciful and the Tudor line not die out in three generations.

As if he fears losing his nerve, Henry will not wait for the jury to take their places in the capital’s Guildhall. Impulsively, he summons his Knight Marshall and the Marshall of the Household to Whitehall in Westminster to give sentence. There is no evidence brought against the boy; oddly, they don’t even call him into court by name. Though Henry worked so hard to give the boy the dishonorable name of a poor drunk man on the watergate in Tournai, they do not use it on this one important document. Though they find him guilty, they do not inscribe the name of Perkin Warbeck on the long roll of the treasonous plotters. They leave his name a blank. Now, as they sentence him to death, they give him no name at all, as if nobody knows who he is anymore, or as if they know his name but dare not say it.

They rule that he shall be drawn on a hurdle through the city of London to the gallows at Tyburn, hanged, cut down while still living, and his innards torn out of his stomach and burned before his face. Then he shall be beheaded and his body divided into four parts, the head and quarters to be placed where the king wishes to put them.

Three days later they try my cousin Teddy before the Earl of Oxford in the great hall at Westminster. They ask him nothing, he confesses to everything that they put to him, and they find him guilty. He says that he is very sorry.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, SATURDAY, 23 NOVEMBER 1499

“You can come in,” I say shortly. I am alone, seated on a chair at the window, looking outwards to the river that my mother loved, listening to the low buzz of talk from my rooms behind me, and the distant cry of the seagulls over the water as they swoop and wheel, their white wings very bright against the gray of the sky.

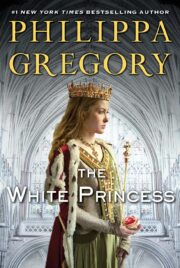

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.