He meets my eyes and I see my own terror reflected back at me, the Queen of England, mother to three precious beloved sons. “No one has power to curse,” he says staunchly, repeating the official belief of the Church. “No mortal woman. What you and your mother said was meaningless, the ravings of distressed women.”

“So nothing will happen?” I ask.

He hesitates and he is honest. “I don’t know,” he says. “I will pray on it. God may be merciful. But it may be that your curse is an arrow into the dark and you cannot stop its flight.”

THE ISLE OF WIGHT, SUMMER 1499

Henry wears a smile like a mask. Lady Katherine is on his arm, everywhere he walks, her beautiful new horse, a black mare, goes shoulder to shoulder with his warhorse. He has taken to riding his warhorse again as if to remind everyone that he is a commander as well as a king. She inclines her head when he talks to her, she smiles as she listens. When he is merry we can hear her laugh, and when he asks her she sings for him, Scots songs, songs from the highlands, filled with melancholy for a land that is lost, until he says: “Lady Katherine, sing us something merry!” and she laughs and starts a round and the whole court joins in.

I watch them as if I were gazing down from far away. I can see them walking together but only dimly hear what they say. I watch them as I know Queen Anne, wife to my Richard, watched me from her high window when we walked in the garden below and he put my hand in his arm and I leaned towards him, longing for his touch. I cannot blame Lady Katherine for ensnaring the King of England, for I did exactly the same. I cannot blame her for being young—she is eight years younger than me—and this summer I am as tired as if I were ninety years old. I cannot blame her for being beautiful—all courts are mad for beauty and she is a delight to watch. But most of all I cannot blame her for turning the king’s head away from me, his true wife, for I think she is doing the only thing she can do to save her husband.

I don’t think she is taken with him as he—vividly—is taken with her. I think she is holding him just where she wants him to be: at arm’s length but within arm’s reach, just at the right proximity so that she can influence him, divert him, soothe him, and soften him, in order to keep her husband alive.

She must have heard—who has not?—the rumors that there is to be a rescue of the boy. The Duchess Margaret sent her embassy to see her beloved protégé and nephew and everyone thinks that she had them whisper to him to wait, that help would come. Everyone knows she will try to save him. She has great influence in Europe, and the greatest kings still call themselves friends of the boy even though they are told he was an imposter. Support is gathering for the boy; if his wife can keep him alive for another season, someone will get him out.

Still the king does not act against the boy but keeps him imprisoned, with constant visitors. Lady Katherine is always at Henry’s side, always there with a quick smile and a soft question to remind him to be merciful to the boy that she married in error. Quick to show him that she can forgive and perhaps—who knows?—one day she may go on to love another? The boy does not have to die to set her free for she is already considering an annulment. Henry, at her side every day, often suggests that she should write to the Pope to ask to be freed from her marriage. It would be little more than a formality. She was tricked into marriage by a man bearing a false name. She was utterly dazzled by a silk shirt. It can be overturned by a single letter from Rome. She assures him that she is considering it, she takes it to God in her three daily prayers. Sometimes she slides a shy sideways smile at him and says that she is tempted by the thought of being a single woman again: free.

Henry, in love for the first time in his life, mooning like a calf, follows her with his eyes, smiles when she smiles, and believes her when she assures him that she thinks of him as a great prince, a puissant king, who can forgive a nonentity like her husband. She understands his greatness by the quality of his mercy. He invites her into his presence chamber when people come to him with requests, and he glances at her to make sure that she is listening when he is generous in forgiving a fine or overturning a judgment. He has her on his arm when he talks with the ambassador from Spain, who tactfully—when speaking before the woman he would make a widow—does not insist that the boy and Teddy be killed at once, though the monarchs of Spain continue to urge the betrothal between Arthur and their daughter and the death of the two young men.

We stay at Carisbrook Castle, behind the gray stone perimeter walls, and we ride out every day into the lush green meadows around the castle, where the larks rise up into a blue sky quite empty of clouds. Lady Katherine declares she has never known such a bonny summer, and the king says that every English summer is like this and that when she has been in England, when she has been happy in English summers for years, she will forget the cold rain of Scotland.

He comes to my room at least once a week and he sleeps in my bed, though often he falls asleep as soon as he lies back on the pillows, tired from riding all day and dancing in the evening. He knows that I am unhappy, but guiltily he dares not ask me what is the matter, for fear of what I might say. He thinks I might accuse him of infidelity, of preferring another woman, of betraying our marriage vows. He wants to avoid any conversation like that, so he smiles brightly at me, and walks briskly with me, and comes to my bed and says cheerfully, “God bless, my dear, good night!” and closes his eyes on my reply.

I am not such a fool as to complain of a disappointment in love. I am not such a fool as to weep that my husband is looking away from me, away and towards a younger, more beautiful woman. It is not for disappointed love that my feet are heavy, and I don’t want to dance or even walk, and my heart aches on waking. It is not for disappointed love for Henry nor the pain of a betrayed wife. It is for the boy in the Tower, and my fear, my increasing fear, that we are far away from London so that the guards Henry has set on him, and their friends in the alleyways and inns, can conspire together, can plot, can send messages, can weave a rope long enough to hang themselves, and hang the boy with them, and that all these tales of the boy in his room and people coming and going are not mistakes, not slackness of the guard, but a part of the story that Henry is weaving that the boy from Tournai, the watergate keeper’s son, faithless and craven to the last, plots with other furtive men of the dark alleys, and leads them like fools to their death.

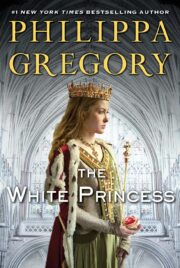

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.