She turns her head away from me. “He could be diminished, he could be dirty, he could be starved, and yet he would still shine,” she says. “He always looks the part that he chooses to play. I heard it from someone who had gone to stare at him, they had gone to laugh at him, but they said that he looked like Jesus: battered and wounded and pained but still the Son of God. They said he looked like a saint. They said he looked like a broken prince, a damaged lamb, a dimmed light. Of course, he can’t be freed. He can never be freed.”

This vengeful old harridan is Henry’s chief and only councillor, so if she refuses me there is no point in approaching Henry. All the same, I wait until he has dined well and drunk deeply and we are seated in his mother’s comfortable private rooms. When she steps out for a moment, I take my chance.

“I want to ask for mercy for the boy,” I say. “And for my cousin Edward. While I am carrying a new child, a new heir for the Tudors, our line must be safe. Surely we can release these two young men? They can be no threat to us now. In our nursery already we have Prince Arthur and Henry, the two girls, and another child is on the way. I would be at peace in my mind, I would be at peace carrying our child, if I know that those two young men were released, into exile, wherever you wish. I would be able to give birth to my child if I could be easy in my mind.” It’s my trump card and I expect Henry to at least listen to me.

“It’s not possible,” he says at once, without even considering the request. Like his mother, he does not look at me as he tells me that my cousin and the boy who passed as my brother are lost to me.

“Why is it not possible?” I insist.

He extends his thin hands. “One”—he counts on his fingers—“the King and Queen of Spain will not send their daughter to marry Arthur unless they are sure our succession is certain. If you want to see your son married, we have to see the boy and your cousin dead.”

I nearly choke. “They can’t demand such a thing! They have no right to order us to kill our own kinsmen!”

“They can. They do. It is their condition for the wedding and the wedding must go ahead.”

“No!”

He continues listing his reasons. “Two—he’s plotting against me.”

“No!” It is such a contradiction of what my servants have told me about the boy in the Tower, a boy quite without his own will. “He is not! It’s not possible. He does not have the strength!”

“With Warwick.”

Now I know that it is a lie. Poor Teddy would plot with no one, all he wants is someone to talk to. He swore loyalty to Henry when he was a little boy; his years in terrible solitude have only made his decision more certain for him. He thinks of Henry now as an all-seeing, all-powerful god. He would not dream of plotting against such a power, he would tremble with fear at the thought of it. “That can’t be so,” I say simply. “Whatever they have told you about the boy, I know that it can’t be said of Teddy. He is loyal to you and your spies are lying.”

“I say it is so,” he insists. “They are plotting and if their plots are treasonous, they will have to die as traitors.”

“But how can they?” I ask. “How can they even plot together? Are they not kept apart?”

“Spies and traitors always find ways to plot together,” Henry rules. “They are probably sending messages.”

“You must be able to keep them apart!” I protest. Then I feel a chill as I realize what is, more probably, happening. “Ah, husband, don’t tell me that you are letting them plot together so that you can entrap them? Say you wouldn’t do that? Tell me that you would not do such a thing? Not now, not now that the boy is in your power, and broken on your orders. Tell me that you wouldn’t do such a thing to poor Teddy, not to poor little Teddy, who will die if you entrap him?”

He does not look triumphant, he looks anxious. “Why would they not refuse each other company?” he asks me. “Why should I not test them and find them true? Why would they not stay silent to each other, turn away from men who come to tempt them with stories of freedom? I have been merciful to them. You can see that! They should be loyal to me. I can test them, can’t I? It is nothing but reasonable. I can offer them each other’s company. I can expect that they shrink from each other as a terrible sinner? I am doing nothing wrong!”

I feel a wave of pity for him, as he leans forwards to the little fire, and I am shaken by nausea at what I fear he is planning. “You are King of England,” I remind him. “Be a king. No one has the power to take that from you. You don’t have to test their loyalty. You can afford to be generous. Be kingly. Release them to exile and send them away.”

He shakes his head. “I don’t feel generous,” he says meanly. “When is anyone ever generous to me?”

GREENWICH PALACE, LONDON, WINTER–SPRING 1499

This is bitter for any woman, and especially hard on Cecily. She will stay away from court until she has put off her black gown. I am sorry for her, but there is nothing that I can do, so I say farewell to the court and step into my beautiful rooms for my first confinement without her.

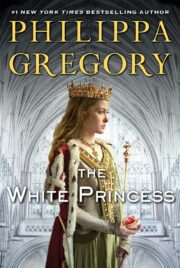

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.