No one now would mistake him for a York prince. He looks like an alehouse brawler, injured many times, who has gone down once too often and cannot rise again. No one will fall in love with his smile now that his front teeth have been kicked in. No one ever again will be swayed by his York charm. No one gathers on the green now to wave at him, no one reports that they have seen him, as if seeing him is an event, something to write home to a village: I have seen the prince! I went to the Tower and I looked towards his window. I saw him wave, I saw his radiant smile.

Now he is a prisoner, like any other in the Tower. He has been sent there to avoid attention and little by little everyone will forget him.

His wife, Lady Katherine, will not forget him, I think. Sometimes I look at her downturned face and I think she will never forget him. She has learned a deep fidelity that I do not recognize. She has changed from her eternal hemming of fine linen to working on a thick homespun. She is sewing a warm jacket, as if she knows someone who lives inside damp stone walls and who will never again bask in the sun. I don’t ask her why she is making a warm thick jacket lined with silks of deep red and blue—and she does not volunteer a reason. She sits in my rooms, her head bent over her sewing, and sometimes she glances up and smiles at me, and sometimes she puts down her work and gazes out of the window, but she never says one word about the boy she married, and she never ever complains that he broke his parole, broke his word to her, and is paying for it.

Margaret comes to visit court, traveling from my son’s court in Ludlow, and of all the places in my rooms, she chooses a seat beside Lady Katherine, saying nothing. Each young woman takes a silent comfort from the other’s nearness. It is part of Henry’s great joke on the House of York that Margaret’s brother, Teddy, is housed in the same tower as Katherine’s husband; he lives on the floor below. The two boys, one the son of George Duke of Clarence, and one who claimed to be the son of Edward King of England, are in rooms so close that if the boy stamped on the floor then Teddy would hear him. Both of them are walled up behind the thick cold stones of our oldest castle for the crime of being a son of York, or—worse—claiming to be one. Truly, it is still a cousins’ war; for here is a pair of cousins, imprisoned for kinship.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, AUTUMN 1498

I miss my mother in this season, when the leaves fall like a blizzard of brown and gold and my windows are hazy with mist in the morning. I miss her when I see the bright shiver of yellow birch leaves reflected in the gray of the river water. Sometimes I can almost hear her voice in the plashing of the water against the stone pilings of the pier, and when a seagull suddenly cries, I almost start up, thinking it is her voice. If it is her son in the Tower, I owe it to her, to him, to my house, to try to get him released.

I approach My Lady the King’s Mother first. I speak to her when she is kneeling in the royal chapel; she has finished her prayers but she is resting her chin on her hands, her eyes on the beautifully jeweled glass monstrance, the wafer of the Host gleaming palely within. She is transfixed, as if she is seeing an angel, as if God is speaking to her. I wait for a long time. I don’t want to interrupt her instructing God. But then I see her settle on her heels and sigh, and put her hand to her eyes.

“May I speak with you?” I ask quietly.

She does not turn her head to glance at me, but her nod tells me that she is listening. “It will be about your bro . . .” she starts and then presses her lips together and her dark eyes flick towards the crucifix, as if Jesus Himself must take care not to hear such a slip.

“It is about the boy,” I correct her. The king and the court have quite given up calling him Mr. Warbeck or Mr. Osbeque. The names, the many names that they pinned on him, never quite stuck. To Henry he was for so long the juvenile threat, the naughty page, “the boy,” that now this is the name that signifies him: a boy. I think this is a mistake, there have been so many boys, Henry has feared a legion of boys. But still Henry likes to insult him with his youth. He is “the boy” for Henry, and the rest of the court follows suit.

“I can do nothing for him,” she says regretfully. “It would have been better for him, for all of us, if he had died when everyone said that he was dead.”

“You mean, after the coronation?” I whisper, thinking of the little princes and the grief in London, while everyone wondered where the children had gone, and my mother was sick with heartbreak in the darkness of sanctuary.

She shakes her head, her eyes on the cross, as if that one great statement of truth can protect her from her constant lies. “After Exeter, they reported him dead.”

I take a breath to recover from my mistake. “So, Lady Mother, since he did not die at Exeter . . . what if he were to agree to go quietly back to Scotland and live with his wife?”

For the first time she looks at me. “You know how it is. If your destiny puts you near to the throne you cannot take yourself away from it. He could go to Ethiop and there would still be someone to run after him and promise him greatness. There will always be wicked people who will want to trouble or unseat my son, there will always be evil snapping at the heels of a Tudor. We have to hold our enemies down. We always have to be ready to hold them down. We have to hold their faces down into the mud. That is our destiny.”

“But the boy is down,” I urge her. “They say that he has been beaten, his beauty is gone, his health is broken. He claims nothing anymore, he agrees to whatever they put to him, he will take any name you choose for him, his spirit is destroyed, he is no longer claiming to be a prince, he no longer looks like a prince. You have defeated him, he is down in the mud.”

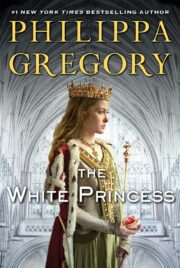

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.