I give a little gasp. “Someone recognized him as Prince Richard? My brother?”

“No. No one would be such a fool. Not at my court. Not surrounded by spies. He was recognized for himself. People saw him as a power, as a person, as a Someone.”

“People just happen to like him.”

“I know. I can’t have that. He has that damned charm that you all have. I can’t have him at court being happy, being charming, looking like he belongs here. But—and this was the problem—I had given my word to him when he surrendered to me. His wife went down on her knees to me, and I gave my word to her. And she held me to it. She would never have allowed me to imprison him or put him on trial.”

He frowns at the glowing embers of the fire, quite unaware that he is confiding to his wife the commands of his mistress.

“And there’s another thing. I established that he is the son of a Flanders boatman—which I thought a very good story at the time—but of course that makes him no subject of mine, so I can’t try him for treason. He’s not my subject, he’s not treasonous. I wish someone had warned me of that when we were going to such trouble to find his parents in Flanders. We should never have found them in Flanders, we should have found them in Ireland, somewhere like that.”

I absorb in silence the cynicism of the creation of the boy’s story.

“So now I have two bad choices: either I can’t try him for treason because he’s foreign, or—”

“Or?”

“Or he’s not foreign but the rightful king!” Henry bursts out laughing, swigs from his tankard, looks at me bright-eyed over the dull pewter. “You see? If he’s who I say he is, then I can’t try him for treason. If he’s who he says he is, then he should be King of England and I am the traitor. Either way I was stuck with him. And every day he grew more and more happy that I was stuck with him. So I had to get him out, I had to make him betray the sanctuary that I had given him.”

“Sanctuary?”

He laughs again. “Wasn’t he born in sanctuary?”

I take a breath. “It was my brother Prince Edward who was born in sanctuary,” I say. “Not Richard.”

“Well, anyway,” he says carelessly. “So the main thing is that I’ve got him out of his comfortably safe billet at my court. Now he’s on the run, I can prove that he’s plotting against me. He’s broken his word that he would stay at court. He’s dishonored his promise to his wife too. She thought he would never leave her; well, he has. I can arrest him for breaking his parole. Put him in the Tower.”

“Will you execute him?” I ask, keeping my voice light and level. “Do you think you will execute him?”

Henry puts down his tankard and throws off his cloak and then his nightgown. He gets into my bed naked, and I just glimpse that he is aroused. Winning excites him, catching someone out, tricking someone, getting money off them or betraying their interest brings him so much pleasure that it makes him amorous.

“Come to bed,” he says.

I show no sign of unwillingness. I don’t know what might depend upon my behavior. I untie the ribbons on my nightgown and I drop it to the floor, I slide between the sheets and he grabs me at once, pulls me beneath him. I make sure that I am smiling as I close my eyes.

“I can’t execute him,” he says quietly, thrusting inside me with the words. I keep my smile on my face as he makes love while speaking of death. “I can’t behead him, not unless he does something stupid.” Heavily he moves on me. “But the joy of him is that he is certain to do something stupid,” he remarks, and his weight bears down on me.

For a manhunt for a known traitor, a claimant to the throne, the ghost that terrorized Henry’s life for thirteen years, the pursuit is curiously leisurely. The guards who slept on duty are cautioned and return to their posts, though everyone expected them to be tried and executed for their part in the escape. Henry sends out messengers to the ports but they travel easily, setting out to north and west, south and east, as if riding for pleasure on a sunny day. Inexplicably, Henry sends out his own personal guard, his yeomen, in boats, rowing upstream, as if the boy might have gone deeper into England, and not to the coast to get back to Flanders, to Scotland, to safety.

His wife has to sit with me while we wait for news. She has not gone back into widow’s black but she is no longer gorgeous in tawny velvet. She wears a dark blue gown and she sits half behind me, so that I have to turn to speak to her, and so that visitors to my rooms, even the king and his mother, can hardly see her, hidden by my great chair.

She sews—heavens, she sews constantly; little shirts for her son, exquisite nightcaps and nightgowns fit for a prince, little socks for his precious feet, little mittens so that he does not scratch his peerless complexion. She bends her head over her work and she sews as if she would stitch her life together again, as if every small hemming stitch would take them back to Scotland, to the days when it was just her and the boy, in a hunting lodge, and he was full of the stories of what he had done and what he had seen and who he said that he was—and nobody asked him what he might do and what he might claim and who he would have to deny.

They find him within a few days. Henry seems to know exactly where to look for him, almost as if he had been bundled, drugged, thrown out of a boat onto the riverbank, and left to sleep it off. They say that he had gone up the valley of the Thames, on foot, stumbling on the tow path, splashing through marshes, following the course of the river through thick woodland and over hedged fields, to the charterhouse at Sheen, where the former prior had once been a good friend to my mother, and where the current prior took the boy in and gave him sanctuary. Prior Tracy himself rode to Henry, asked for an audience, and begged for the young man’s life. The king, bombarded with pleas for clemency, with a holy prior down on his knees refusing to rise until the boy is granted his life, once again decides to be gracious. With his mother seated beside him, as if they are both judges on the Last Day, he rules that the boy should stand on a scaffold of empty wine barrels for two days, to be seen by everyone who passes by, mocked, cursed, scorned, and a target for any urchin with a handful of filth, and then be taken to the Tower of London, and there be imprisoned pending the king’s pleasure: that is, forever.

THE TOWER OF LONDON, SUMMER 1498

The window that overlooks the green was where their little faces could sometimes be seen, and sometimes they would wave at people who gathered on the green to see them or, coming out of chapel, call a blessing to them. Now there is one pale face at the window—the boy’s—and people who see him closely say that he has lost his looks, he is almost unrecognizable for the bruises on his face. His nose has been broken and is ugly, squashed cross-wise against his handsome face. He has a bloody scar behind his ear where someone kicked him when he was down, and the ear itself is half torn away and has gone sticky and fetid.

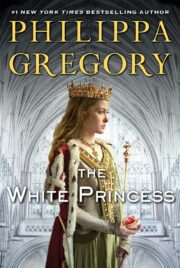

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.