My mother puts her arm around my waist, watching the procession with me. She says nothing, but I know that she is thinking of the day that we stood in sanctuary in the dark crypt below the abbey chapel, watching the royal barges go down the river, when they crowned my uncle Richard and passed over the true heir, my brother Edward. I thought then that we would all die in the darkness and solitude. I thought that an executioner would come for us silently one night. I thought I might wake briefly with the weight of a pillow on my face. I thought that I would never see sunshine again. I was a young woman then, and I thought that sorrow as deep as mine could only lead to death. I was grieving for my father and frightened by the absence of my brothers, and I thought that soon I would die too.

I realize that this is the third victorious coronation barge to sail past my mother. When I was just a little girl and my brother Edward was not even born, she had to hide in sanctuary as my father the king was driven out of England. They brought back the old king and my mother stooped to look out of the low dirty window of the crypt under Westminster Abbey church to see Lady Margaret and her son Henry sail down the river in their pomp to celebrate the victory of the restored King Henry of Lancaster.

I was only a little girl then, and so I don’t remember the ships sailing by nor the triumphant mother and her little son on a barge decked with red roses; but I do remember the pervasive scent of river water and damp. I do remember crying myself to sleep at night, utterly bewildered as to why we were suddenly living like poor people, hiding in a crypt under the chapel instead of enjoying the most beautiful palaces of the kingdom.

“This is the third time you have seen Lady Margaret sail by in triumph,” I remark to my mother. “Once when King Henry was restored and she led the race to get to his court and introduce her son, once when her husband was high in Richard’s favor and she carried Queen Anne’s train at the coronation, and look, now she sails by you again.”

“Yes,” she acknowledges. I see her gray eyes narrow as she watches the gloriously gilded barge and the proud flap of the standards. “But I always find her so very . . . unconvincing, even in her greatest triumphs,” she says.

“Unconvincing?” I repeat the odd word.

“She always looks to me like a woman who has been badly treated,” my mother says, and she laughs joyously out loud, as if defeat is just a turn of the wheel of fortune and Lady Margaret is not on the rise and an instrument of the glorious will of God as she thinks, but has just been lucky on this turn, and is almost certain to fall on the next. “She always looks to me like a woman who has much to complain about,” my mother explains. “And women like that are always badly treated.”

She turns to look at me, and laughs aloud at my puzzled expression. “It doesn’t matter,” she says. “At any rate, we have her word that Henry will marry you, as soon as he is crowned, and then we’ll have a York girl on the throne.”

“He shows few signs of wanting to marry me,” I say dryly. “I am hardly honored in the coronation procession. It’s not us on the royal barge.”

“Oh, he’ll have to,” she says confidently. “Whether he likes it or not. The Parliament will demand it of him. He won the battle, but they won’t accept him as king without you at his side. He has had to promise. They’ve spoken to Thomas, Lord Stanley, and he, of all men, understands the way that power lies. Lord Stanley has spoken to his wife, she has spoken to her son. They all know that Henry has to marry you, like it or not.”

“And what if I don’t like it?” I turn to her and put my hands on her shoulders so she cannot glide away from my anger. “What if I don’t want an unwilling bridegroom, a pretender to the crown, who won his throne through disloyalty and betrayal? What if I tell you that my heart is in an unmarked grave somewhere in Leicester?”

She does not flinch, but confronts my angry grief, her face serene. “Daughter mine, you have known for all your life that you would be married for the good of the country and the advancement of your family. You will do your duty like a princess, wherever your heart is buried, whoever you want or don’t want, and I expect you to look happy as you do it.”

“You’ll marry me to a man that I wish were dead?”

Her smile does not waver. “Elizabeth, you know as well as I do that it is rare that a young woman can marry for love.”

“You did,” I accuse.

“I had the sense to fall in love with the King of England.”

“So did I!” breaks from me like a cry.

She nods and puts her hand gently on the nape of my neck, and when I yield to her, she pulls my head to her shoulder. “I know, I know, my love. Richard was unlucky that day, and he had never been unlucky before. You would have thought he was certain to win. I thought he was certain to win. I too staked my hopes and my happiness on his winning.”

“Do I really have to marry Henry?”

“Yes, you do. You will be Queen of England and return our family to greatness. You will restore peace to England. These are great things to achieve. You should be glad. Or, at the very least, you can look glad.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, NOVEMBER 1485

They restore Henry’s mother to her family fortune and properties; nothing is more important than building the wealth of this most powerful king’s mother. Then they promise to pay my mother’s pension as a dowager queen. They also agree that Richard’s law that ruled my mother and father were never legally married must be dismissed as a slander. More than that, it must be forgotten, and nobody is ever to repeat it. At a stroke of the pen from the Tudor Parliament, we are restored to our family name and I and all my sisters are legitimate princesses of York once more. Cecily’s first marriage is forgotten; it is as if it never was. She is Princess Cecily of York once again and free to be married to Lady Margaret’s kinsman. In Westminster Palace, the servants now bend their knee to present a dish, and everyone calls each of us “Your Grace.”

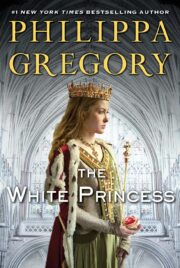

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.