I throw a robe over my gown and hurry out of the door with her. There is a babel of noise and confusion, the bell ringing and men shouting and people running from one place to another. Without needing to say a word, Maggie and I dash side by side to the rooms of the royal nursery and there, thanks to God, are Harry, Margaret, and Mary, the two older ones tumbling down the stairs with their nursemaids shrieking to them to go as fast as they can but to be careful, and Mary big-eyed in the arms of her nursemaid. I drop to my knees and hold the oldest two to me, feeling their warm little bodies, feeling my heart thud with relief that they are safe. “There is a fire in the palace,” I tell them. “But we are not in danger. Come with me and we will go outside and watch them put it out.”

A guard of yeomen go running past me, carrying flails and buckets of water. I tighten my grip on my children’s hands. “Come on,” I say. “Let’s go outside and find your brother and your father.”

We are halfway down the gallery to the great hall when the door to Lady Katherine’s room flies opens and she dashes out, her black cape flung over her white nightgown, her dark eyes wide, her hair a rich tumble around her face. When she sees me she halts. “Your Grace!” she says and curtseys low and stays down, waiting for me to go past her.

“Never mind that, come at once,” I say. “There is a fire, come at once, Lady Katherine.”

She hesitates.

“Come!” I command. “And all your household with you.”

She pulls her hood over her hair and hurries to walk behind me. As I go on with my children I just glimpse, out of the corner of my eye, the young man that is called Perkin Warbeck, wrapped in a cloak, slide from Lady Katherine’s inner private room and fall in behind us, with my household.

I glance back to be sure, and he meets my gaze, his smile warm and confident. He shrugs and spreads his hands, a gesture wholly French, completely charming. “She is my wife,” he says simply. “I love her.”

“I know,” I say, and hurry onwards.

The front doors are wide open and they have made a line of people passing pails of water up the stairs. Henry is in the stable yard, making them hurry, drawing water from the well, urging the lad to work harder at the pump. It is painfully slow, we can smell the acrid hot smoke on the wind and the bell tolls loudly as the men shout for more water and say that the flames are taking hold. Arthur is there with Sir Richard, his guardian, wearing nothing but his breeches and a cape over his bare shoulders.

“You’ll freeze to death!” I scold him.

“Go and get a jacket from our traveling carts,” Maggie orders him. “They’re not unpacked yet.”

Arthur ducks his head in obedience to her and goes to the stables.

“It’s a terrible fire, in the wardrobe rooms, you’ll lose your gowns, and God knows how many jewels!” Henry shouts at me above the noise. I can hear a crack as the expensive window glass shatters in the heat and then there is a noise like a blast as one of the roof beams caves in and the flames shoot upwards like an explosion.

“Is everyone out of the building?” I shout.

“As far as we can tell,” Henry says. “Except . . . my love, I am sorry . . .” He steps away from the line of men frantically slopping pails of water one to another. “I am so sorry, Elizabeth, but I am afraid the boy is dead.”

I glance behind me. Lady Katherine is there, but the boy has melted into the crowds of people milling around the front doors of the palace, starting back as another roar comes from the fire and flames lick out of an upper window.

“Will you tell her?” Henry asks me. “There is no doubt that he is lost to the blaze. He was sleeping in the wardrobe rooms, of course, and they were locked. It’s where the fire started. We must prepare ourselves for his death. It’s a tragedy, it’s a terrible tragedy.”

Something about Henry alerts me. He is strangely like our son Harry, when he looks at me with his blue eyes as honest and as open as a summer sky and tells me some great fib about his homework, or his sister, or his tutor.

“The boy is dead?” I ask. “He has died in the fire?”

Henry looks down, shrugs his shoulders, heaves a sigh, puts his hand over his eyes as if weeping. “He can’t have got out of that,” he said. “It was raging by the time anyone knew of it, it was like hell.” He puts out his hand to me. “He won’t have suffered,” he says. “Tell her that it would have been merciful and quick. Tell her that we are all so sorry.”

“I’ll tell her what you say,” is all I promise, and I leave my husband to command the men who are bellowing for sand to fling on the flames and “Water! More water!” I walk back to where Lady Katherine is standing with Harry and Margaret beside her.

“Lady Katherine . . .” I beckon her out of their hearing and she drops a quick kiss on my son’s copper head and comes to me.

“The king believes that your husband was in his bed in the wardrobe rooms,” I say levelly. There is no intonation in my voice at all, I am as bland as milk.

She nods, expressionless.

“The king fears that he must have died in the blaze,” I say.

“It is the wardrobe rooms that are on fire?”

“It’s where the fire started, and it has taken hold.”

Both of us absorb the curious fact that the fire should start not in the kitchen, nor the bakery, nor even in the hall where there are great fires always burning, but in the wardrobe rooms where the strictest watch is kept, where the only naked flames are the candles, which are lit when the seamstresses are at work and doused when they leave for the evening.

“I suppose,” I observe, “that since the king thinks that your husband is dead, he will not look for him.”

She is very still as she takes in this thought, then she looks up at me. “Your Grace: the king holds our son, my little boy. I could not leave without him. And my husband will not leave without us. I see that he has a chance to escape, but I don’t even have to ask him what he will do; he would never leave without us. He would have to be carried out half-dead to go without us.”

“It may be that this chance has come from God,” I point out. “A fire, confusion, and the expectation of his death.”

She meets my eyes. “He loves his son, and he loves me,” she says. “He is as honorable . . . as honorable as any prince. And he has come home now. He will not run away again.”

Gently, I touch her hand. “Then he had better reappear soon, with some explanation,” I advise her shortly, and I walk away from her to stand with my children, and promise them that their ponies will have been taken from their stables and are safely turned out in the damp winter fields.

In the morning the flames are doused down but the whole palace, even the gardens, smells terribly of wet timbers and dank smoke. The wardrobe rooms are the great storehouse of the palace and priceless treasures have been lost to the flames, not just the costly gowns and ceremonial costumes, but the jewels and the crowns, even the gold and silver plate for the table, some of the best pieces of furniture and stores of linen. Thousands of pounds of goods have been destroyed, and Henry pays men to sift through the embers for jewels and melted metals. They bring up all sorts of rescued objects, even the lead from the windows has melted and twisted out of shape. It is terrible what has been lost; it is amazing what has survived.

“How did Warbeck ever get out of this alive?” Lady Margaret bluntly demands of Henry, as the three of us stand, looking at the ruin that was the king’s apartments, the charred roof beams open to the sky still smoking over our heads. “How could he survive it?”

“He says that his door caught fire and he was able to kick it open,” Henry says shortly.

“How could he?” she asks. “How could he not die of the smoke? How could he not be burned? Someone must have let him out.”

“At least no one was killed,” I say. “It’s a miracle.”

The two of them look at me, their faces like a mirror of suspicion and fear. “Someone must have let him out.” The king repeats his mother’s accusation.

I wait.

“I shall make inquiry among the servants,” Henry swears. “I will not have a traitor in my palace, in my own wardrobe rooms, I will not be betrayed under my own roof. Whoever is protecting the boy, whoever is defending him, should take warning. Whoever saved him from the fire is a traitor, as he is. I have spared him so far, I will not spare him forever.” Suddenly he turns on me. “Do you know where he was?”

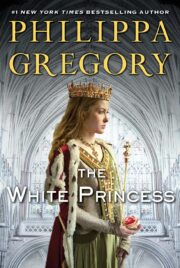

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.