She drops him a low, deferential curtsey and when she rises up he takes her hand. I see her lower her eyes modestly, and the little hint of her smile, and finally I understand why she has been sent to be my lady-in-waiting, and why her husband rides freely among the king’s men. Henry has fallen in love for the first time in his life, and with the worst choice he could possibly have made.

His mother, who was watching every step of her son’s victorious arrival, invites me to her rooms that evening before the grand victorious dinner. She tells me that Henry has appointed two of my ladies-in-waiting and taken two from her court to serve Lady Katherine until he can find suitable ladies to wait on her. Apparently Lady Katherine is to have a little court of her own, and her own rooms; she is to live as a visiting princess of Scotland and be served on bended knee.

Lady Katherine has been invited to go to the royal wardrobe to choose a gown suitable for the feast to celebrate the king’s victory. It seems that the king would like to see her wear another color, other than black.

I remember, wryly, that once I was commanded to wear a gown of the same cut and color as Queen Anne, and that everyone remarked how beautiful I was, standing beside her in a matching gown, and her husband could not take his eyes off me. It was the Christmas feast before the queen died, and she and I wore the same red gown, except she wore it as if it were her shroud, poor lady, she was so white and thin. I stood beside her and the color scarlet put a flush in my cheek and brightened the gold of my hair and the sparkle in my eyes. I was young, and in love, and I was heartless. I think of her now, and her calm dignity when she saw me dance with her husband, and I wish I could tell her that I am sorry, and that now I understand far more than I did then.

“Have you asked the king when Lady Katherine is going home?” My Lady demands abruptly. She is standing with her back towards a mean fire, her hands tucked into her sleeves. The rest of the room is cold.

“No,” I say. “Will you ask him?”

“I will!” she exclaims. “I certainly will. Have you asked him when Pero Osbeque is to go to the Tower?”

“Is that his name now?”

She flushes, furious. “Whatever he is called. Peter Warboys, whatever they call him.”

“I have had very little speech with His Grace,” I say. “Of course his lords and the gentlemen from London wanted to ask him about the battle and so he went to his presence chamber with them all.”

“Was there a battle?”

“Not really, no.”

She takes a breath and looks at me, a sly cautious look as if she is unsure of her ground. “The king seems very taken with Lady Katherine.”

“She’s a very beautiful woman,” I agree.

“You must not mind . . .” she goes on. “You must not object . . .”

“Object to what?” It is hardly a challenge, my voice is so calm and pleasant.

“Nothing.” She loses her nerve before my smiling serenity. “Nothing at all.”

Lady Katherine comes to my rooms before dinner obediently wearing a new gown from the royal wardrobe but keeping to her chosen color of deepest black. She is wearing the gold brooch of intertwined hearts on a thin chain of gold, lying over a veil of white lace that covers her shoulders. The warm cream of her skin glows under the fabric, veiled and visible at the same time. When the king enters my presence chamber, his eyes rake the room for her, and when he sees her he gives a little start, as if he had forgotten how beautiful she is, and he is shaken by desire all over again. She curtseys as politely as the other ladies, and when she comes up she is smiling at him, a hazy smile like a woman who laughs through her tears.

Henry gives me his arm to lead me in to dinner and the rest of the court take their places behind us, my ladies following me in order of precedence, the gentlemen behind them. Lady Katherine Huntly, her dark eyes fixed modestly on the ground, takes her rightful place behind My Lady the King’s Mother. As Henry and I lead the way down the wide stone stairs to the great hall to the blast of trumpets and the murmur of applause from the people who have crowded into the gallery to see the royal family at their dinner, I sense, more than I actually see, that the boy who is to be called Peter Warboys, or perhaps Pero Osbeque or John Perkin, has walked past the woman who was once his wife, bowed his head low to her, and taken his place with the other young noblemen of Henry’s court.

The boy seems to be at home at court. He goes from hall to stable to hawking mews to gardens and he is never seen to miss his way, never asks anyone which is the direction of the treasure house, or where would he find the king’s tennis court? He will fetch a pair of gloves for the king without asking where they are kept. He is comfortable with his companions, too. There is an elite of handsome young men who lounge in the king’s rooms and run errands for him, who like to call at my rooms to listen to the music and chatter with my ladies. When there are cards they are quick to take a hand, if there is archery they will take a bow and excel each other. Gambling, they are free with money; dancing, they are graceful on the floor; flirting is their principal occupation, and every one of my ladies has a favorite among the king’s young men and hopes that he sees her half-hidden glance.

The boy falls into this life as if he had been born and bred at a graceful court. He will sing with my lutenist if invited, he will read in French or Latin if someone hands him the storybook. He can ride any horse in the stables with the relaxed, easy confidence of a man who has been in the saddle since he was a boy, he can dance, he can turn a joke, he can compose a poem. When they put on an impromptu play he is quick and witty, when called to recite he has lengthy poems by heart. He has all the skills of a well-educated young nobleman. He is, in every way, like the prince he pretended to be.

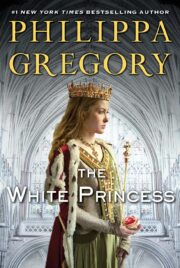

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.