My mother shrugs her shoulders. “What if they cheered for her? What if they called for us?” she says quietly. “You know how people would cheer for her, if they saw her. You know how Londoners love the House of York. What if the people saw us and called for my nephew Edward of Warwick? What if they booed the House of Tudor and called for the House of York? At his coronation? He’s not going to risk it.”

“There’ll be York kinsmen there,” Katherine points out. “Your sister-in-law Elizabeth has turned her coat, as her husband the Duke of Suffolk has changed sides again. Her son, John de la Pole, that King Richard named as his heir, has begged Henry’s pardon and so they will be there.”

My mother nods. “So they should be,” she says. “And I am sure they will serve him loyally.”

My aunt Katherine gives a short snort of laughter and my mother cannot stop her smile.

I go to find Cecily. “You’re to be married,” I say abruptly. “I heard Mother and Aunt Katherine talking.”

She turns pale. “Who to?”

I understand at once that she is afraid that she is to be humiliated again by a marriage to some lowly supporter of the Tudor invasion. “You’re all right,” I say. “Lady Margaret is standing your friend. She’s marrying you to her half brother, Sir John Welles.”

She gives a shuddering sob and turns to me. “Oh, Lizzie, I was so afraid . . . I’ve been so afraid . . .”

I put my arm around her shoulders. “I know.”

“And there was nothing I could do. And when Father was alive, they all used to call me Princess of Scotland, as I was to marry the Scots king! Then to be pushed down to be Lady Scrope! And then to have no name at all! Oh, Lizzie, I’ve been vile to you.”

“To everyone,” I remind her.

“I know! I know!”

“But now you’ll be a viscountess!” I say. “And no doubt better. Lady Margaret favors her family above everyone else, and Henry owes Sir John a debt of gratitude for his support. They’ll give him another title and lands. You’ll be rich, you’ll be noble, you’ll be allied to My Lady the King’s Mother, you’ll be—what?—her half sister-in-law, and kinswoman to the Stanley family.”

“Anything for our sisters? What about our cousin Margaret?”

“Nothing yet. Thomas Grey, Mother’s boy, is to come home later.”

Cecily sighs. Our half brother has been like a father to us, fiercely loyal for all of our lives. He came into sanctuary with us, only breaking out to try to free our brothers in a secret attack on the Tower, serving at Henry’s court in exile, trying to maintain our alliance with him, and spying for us all the while. When Mother became sure that Henry was an enemy to fear, she sent for Thomas to come home, but Henry captured him as he was leaving. Since then, he has been imprisoned in France. “He’s pardoned? The king has forgiven him?”

“I think everyone knows he did nothing wrong. He was a hostage to ensure our alliance, Henry left him as a pledge with the French king, but now that Tudor sees that we’re obedient, he can release Thomas and repay the French.”

“And what about you?” Cecily demands.

“Apparently, Henry’s going to marry me, because he can’t get out of it. But he’s in no sort of hurry. Apparently, everyone knows that he has been trying to renege.”

She looks at me with sympathy. “It’s an insult,” she says.

“It is,” I agree. “But I only want to be his queen; I don’t want him as a man, so I don’t care that he doesn’t want me as his wife.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, 30 OCTOBER 1485

The rowers are all in livery of green and white, the Tudor colors, the oars painted white with bright green blades. Henry Tudor has commanded springtime colors in autumn; it seems that nothing in England is good enough for this young invader. Though the leaves fall from the trees like brown tears, for him everything must be as green as fresh grass, as white as May blossom, as if to convince us all that the seasons are upside down and we are all Tudors now.

A second barge carries My Lady the King’s Mother, seated in her triumph on a high chair, almost a throne, so that everyone can see Lady Margaret sailing into her own at last. Her husband stands beside her chair, one proprietorial hand on the gilded back, loyal to this king as he swore he was loyal to the previous one, and the one before that. His motto, his laughable motto, is “Sans changer,” which means “always unchanged,” but the only way the Stanleys never change is their unending fidelity to themselves.

The next barge carries Jasper Tudor, the king’s uncle, who will carry the crown at the coronation. My aunt Katherine, the prize for his victory, stands beside him, her hand resting lightly on his arm. She does not look up at our windows, though she will guess we are watching. She looks straight ahead, steady as an archer, as she goes to witness the crowning of our enemy, her beautiful face quite impassive. She was married once before for the convenience of her family, to a young man who hated her; she is accustomed to grandeur abroad and humiliation at home. It has been the price she has paid for a lifetime of being one of the beautiful Rivers girls, always so close to the throne that it has bruised her like a wound.

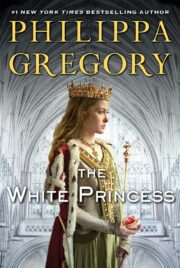

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.