“Careful. I’ll start thinking you care.”

He turned his head slowly, chancing a glance at her then…intrigued by what he saw in the moonlit night.

She did care. She didn’t want to, but she did.

“I would care if you were caught and led the Taliban to us,” she said grumpily. “My father is old. I do not wish him to die at the hands of those barbarians.”

Yeah, there was that.

“Does your father know you’re up here?”

“He is asleep.”

The old man slept a lot. During the day, he napped quietly either in the back courtyard or in the shade of his front stoop, occasionally waking up to hold court with villagers who stopped to speak with him. He seemed oblivious to what went on inside his own house. It made him wonder if the old man might be ill.

Her father’s name was Wakdar Kahn Kakar. Kakar, she had told him one day when he’d asked, was their tribe’s name.

“Wakdar means ‘man of authority,’” she’d said, then added, “Do not speak to him unless he speaks to you first. Then you should address him as Shaghalai Kakar, to show respect.”

“So what is he? Some sort of tribal elder?”

“He is the malik, the village representative, and speaks for the people at the shura, the village council.”

“So everyone brings him their problems.”

“And he takes them to the mullah—the religious leader—who decides if they will be presented to the council.”

“How would the mullah like it if he knew an American askar was hiding in the malik’s house?”

She’d had nothing to say to that. But he suspected she thought about it a lot. Most likely, she thought about it tonight up on the roof.

“Maybe I should run and save you both a lot of trouble.”

It was her turn to look at the sky. “Where would you go? How far would you get?”

“That was a joke.” He could barely walk, let alone run. Even if his leg wasn’t a problem, the vertigo would take him down before he got ten yards. “Joke? A funny statement?” he clarified when she said nothing.

“I know what a joke is.”

“Yet clearly, it’s a concept you don’t understand.” He crossed his arms and made a pillow for his head.

He realized now that he could easily start living for the night when he could come up here and see the sky and not breathe air that smelled of strong spices and her father’s tobacco smoke. Up here, it smelled of living things instead of the bat shit and the must of the cave where he’d been for so long. Other foul smells hovered at the edge of his memory. Smells that he associated with pain but couldn’t pinpoint.

She started to get up. “We should go back inside. Come. I will help you down.”

“Not yet. Relax, OK? Even the bad guys snuggle up to their RPGs and sleep sometimes. They’re not looking for me tonight.”

She did not find his sense of humor remotely funny. He found it ironic that he had one.

The truth was, Rabia found nothing funny. Then again, how the hell would he know? It had only been a couple of weeks since he hadn’t been blitzed on opium.

“So if you’re not worried I’ll run, then why are you up here?” Unaccompanied women did not venture out after dark in this land of sharia law and public stoning. “Or are we back to the possibility that you were worried about me?”

The biggest joke of all. She might not know how to handle the sexual undertones rattling around between them, but she knew how to erect distance. When she again said nothing, he decided it was time to find out more about his reluctant nurse and host. That was the thing about opium. He had pretty much not given a damn about anything while he was on it. Now he had questions. Now his head was clear—empty but clear.

“What do you do, Rabia jana?” he asked surprising her by adding the formality used when addressing young women. “When you aren’t risking your neck hiding American soldiers? You speak English. You’re educated. That’s clear.” It was also unusual. Ninety percent of Afghan women were illiterate.

There went another one. A random piece of information he hadn’t known that he knew.

“I am a teacher of girls. My school is in Kabul.”

“Kabul?” This village was in the Kandahar Province, south of Kabul and west of the Pakistan border. Another mysterious nugget of information.

“You don’t normally live here?”

“I was born here. My father sent me to live with his brother in Kabul when I was sixteen. Right after the Taliban were removed from power.”

“In 2001, when the U.S. and Coalition forces launched an offensive.”

She looked at him sharply. “Do you realize what you said?”

Not until it had come out of his mouth. “Yeah. I do. Like I said, that’s been happening on and off lately.”

“Since you’ve been off the opium.”

“Yes. And it seems to happen when we talk. That day in the kitchen. Now. Conversation seems to trigger these… memories. Keep talking to me.” He worked to contain his excitement. This felt like a breakthrough. If he could remember things about Afghanistan, maybe he could remember something about who he was.

“You are right,” she said, and he could hear a barely contained excitement in her voice, too. “The American and Coalition forces defeated the Taliban in 2001. Radical sharia law was thrown out. Girls returned to school. Women went to work. At least, in some provinces.”

“But not in Kandahar?”

“No. Not in Kandahar.”

“No wonder you prefer Kabul.”

“What I prefer are basic human rights. The Taliban have been ousted from political power, but they still rule by terror here in Kandahar Province. Women here are expected to follow sharia law. We have no rights. We are chattel. Only because of my father, only because he is a malik, was he able to send me to Kabul, where I went to school.”

“To become a teacher.”

“Yes. And to become active in the Afghan women’s movement. Because of us, there are women in parliament now. Some of us even drive.”

Her statement triggered another memory. “You were driving when you found me.”

“Yes.” Pride filled her tone. He understood why. She was a trailblazer.

“Isn’t it dangerous for you to drive in this part of Afghanistan?”

“Because of the heavy Taliban presence, yes. But I studied hard to pass the test and earn the right to drive as any man does.”

“That doesn’t explain why you risked driving through Taliban territory.”

“My father called me home. I drove during daylight hours to avoid the night patrols.”

She was not only beautiful, she was also smart and brave, and she honored her father. Here a daughter obeyed her father with no questions asked.

“Your father is ill, isn’t he?”

She drew a long breath. “He is old. And yes, he is not as well as he once was.”

He had noticed that the old man barely picked at his food. And then there was the excessive sleeping. “He should see a doctor.”

“He refuses. He is a stubborn man, my father. Like you, I believe, are a stubborn man.” She stood then and held out her hand. “Do not tell me no again. We must go inside. And you will accept my help.” Sheer determination filled her eyes.

“And if I say no?” Because she looked so stern, he couldn’t resist baiting her.

“Then you will be responsible for me not getting any sleep this night.”

She’d known exactly how to get to him. “That’s not playing fair.”

“What about life is fair?”

Didn’t he know it? And yet this exchange made him smile.

He took her hand and slowly rose to a sitting position. Standing had gotten easier, but he always had to take extreme care with sudden movements, or he’d land on his ass, sweating like a marathon runner in the last mile, swallowing back his dinner, and hanging on to the world while it spun out of control.

“Wait until you are steady,” she said when he finally had his feet beneath him.

They stood side-by-side in the moonlight, his weight on his good leg, his world fairly level. It struck him then that for a woman of such strength, she was neither tall nor heavily built.

“How tall are you?”

She told him in Pashto.

That calculated in English to five feet four inches, which made him around five-foot-eight or -nine since the top of her head was level with his nose.

“Ready?” she asked uncertainly.

Ten feet separated them from the edge of the flat roof. “I can do this.”

Only the first step out of the gate proved he couldn’t. His bad leg promptly cramped, and he started to go down. Rabia moved in fast. She tucked herself under his shoulder and wrapped an arm around his waist, steadying him.

“That went well,” he gritted out as he rode through the burning ache in his shin.

“I suspect your leg was once broken and did not heal well,” she said, as he leaned on her for support.

“Bastards wouldn’t set it. They just dumped me in that hole and—”

He stopped, felt his gut tighten, as a wrenching memory of a hole in sand-colored soil crystallized through a murky fog.

Four feet deep, four feet wide, six feet long.

Covered with a crude lattice hatch of rough wood that only opened once a day when they threw starvation rations of food and water at him. If he was quick enough, he tossed out the contents of his waste bucket.

Snow and ice covered him.

Rain washed in.

Sun burned and baked.

He carved lines into the dirt wall with his knuckle to mark the time that crawled like the snakes that sometimes slithered into the hole with him.

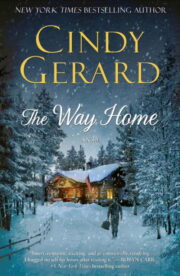

"The Way Home" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Way Home". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Way Home" друзьям в соцсетях.