The child psychiatrist tried to get me to confess to hating my body, then pursed her lips and gave me soft, sad eyes when I wouldn’t.

But why would I hate my body?

Her attention-seeking-behavior theory made even less sense. It was the opposite. I wanted to disappear, but that fact didn’t have anything to do with my deal with God either.

Then she tried to convince me I was punishing my parents for giving up on Lena. I already disliked her, with her frizzy bun and coffee breath, but now I had a reason to hate her. She wasn’t allowed to talk about my parents like she knew them. They weren’t moving on. They were moving into themselves—away from each other and me and the world. Mom was sure that Lena was still alive, living with hippies or polygamists or devil worshippers or whoever. And Dad had transformed from a man who built birdhouses for Mom’s garden to a man who kicked holes in walls. Why would I want to punish them more?

I would die, the shrink finally told me, if I didn’t start eating.

I pretended not to hear her. I didn’t tell her that God would save me. I knew he would, though. Not because I needed saving, but because he was going to bring back my sister.

It wasn’t until spring that I started eating again. Hunters found Lena’s body in the woods only forty miles south. Of course nobody told me the details, but I read them years later online. Naked, raped, strangled, discarded, frozen, thawed, and gnawed on by wild animals. That was how god brought her back to me.

The frizzy-bunned shrink took full credit for my recovery, and I never told her or my parents about my pact with god. Just Mo, when we were fourteen.

He listened, then asked who won.

“Won? It wasn’t a contest, Mo. It was a deal.”

“A deal? But what does God have to gain from you not eating?” he asked.

“I don’t know. That’s not really the point.” I’d expected sympathy, not a critique. But I’d forgotten that Mo thinks first and feels later. “It made sense at the time. I was ten, Mo.”

“So you started eating again because you realized God doesn’t make deals?” he asked.

“No. I started eating because there is no god.”

He said nothing. Then finally, “Hmm.”

“What does that mean?”

“What if you’re wrong? What if there is one and he just doesn’t make deals? Or what if he does make deals and the feeding tube was breaking it? What if you lost?”

“It wasn’t a contest.”

“Sounds like one to me.”

“Forget it.”

But he didn’t forget it. The next day he slid an envelope into my locker with a bumper sticker inside—one of those Christian fish symbols with feet and DARWIN written across it. The accompanying note said: Sorry. I’m an ass. You’ve totally earned atheism.

That’s something Mo can do better than anyone else: apologize. It isn’t that easy for most people to say sorry and mean it, but I knew he meant it.

At the time, I didn’t have a car, and I was pretty sure Mom wouldn’t let me use her Tahoe to mock Christianity, so I put the sticker on my bathroom mirror instead. My parents never asked about it.

“Why don’t you head out,” Reed says. My head snaps up and into the present. “I can finish,” he adds.

I stare down at the rag in my hand. How long have I been wiping circles with this same dirty rag? He must think I’m crazy. I glance at the clock. “It’s okay. My ride won’t be here for another ten minutes.”

Having Mo pick me up is the only thing keeping Mom and Dad from freaking out completely about the fact that I’m working here.

Reed tosses me a fresh rag. “You want to do the booths then?”

“Sure.” I drop my mine into the murky-watered blue bucket and take the warm rag to the first booth. “So, how many summers have you worked here?” I ask.

“Last year was my first.”

I give him a moment to elaborate or ask me a question, but he doesn’t. Not surprising since so far I’ve learned only what I can see:

He drinks his already-too-sweet Mr. Twister iced teas with two packets of sugar.

He listened to Flora gripe about her landlord, then let her make fun of his geeky glasses.

He cleans the geeky glasses with the corner of his apron, and for just the moment that his face is bare I think his eyes could tell stories. But then he puts them back on, and he’s closed again.

He looks vaguely uncomfortable when Rachel or Clara or one of the other college girls tries to flirt with him.

The cookbooks he reads during his break aren’t the kind that my mom has, with pictures of bubbling casseroles, promising meals with five ingredients in less than ten minutes. The one he left on the table in the back had recipes with a zillion ingredients, half of which I’d never heard of, and whole chapters on the making your own cheese and discerning the quality of truffle oil.

“What’s culinary school like?” I ask.

“It’s hard. Harder than I thought it would be.”

“Do you like your classes?”

“Yeah.”

“My mom always says she wishes she went to culinary school,” I say. “She watches Top Chef like it’s her job.”

“Does she work?”

“She used to teach Victorian Lit at U of L.”

“Really?” Suddenly he’s interested, and I’d kill for something intelligent to say. Our eyes lock. He’s wondering if I’m more than just some dumb blonde. I look away.

“She doesn’t teach anymore?” he asks.

I tuck the hair that’s escaped my ponytail behind my ear. What to say?

She went on sabbatical after Lena disappeared and then just never went back. She was always going to. I can’t remember exactly when we stopped hearing next year, but it was no longer a question we asked.

“She’s working on a book,” I say, though I don’t actually believe this. She talked about writing some poet’s biography a few years back, but unless planting peonies is research for the book, the biography project is on hold.

“I think your ride’s here,” Reed says.

I hadn’t noticed the sound of the truck pulling in, but I can hear the familiar grumble now. I pull back the blinds and peer out into the dark parking lot. Sure enough, there’s Mo. He was stoked about the chauffeuring arrangement since he’s without wheels otherwise. Who knows what he’s been up to since he dropped me off this morning, but judging from the bug carnage on my grille, it was far away. Last shift he drove out to Mammoth Cave with Bryce.

Mo flashes his brights, my brights, into the shop, then lays on the horn, two long blasts. Nice. Heaven forbid he have to wait for a whole minute.

“Go,” Reed says. “I’ll finish up.”

“You sure?” I’m already untying my apron.

“Of course.”

I glance up and he’s watching me. My fingers fumble with the knot at my waist, but I can’t seem to wriggle my thumbnail into the center. How did this thing get pulled so tight?

He squints, gives a half smile. “You need some help with that?”

“I’ve got it,” I say, finally looking down.

I chuck the apron in the dirty linens bag and give him an awkward wave good-bye, but he’s not looking anymore. He’s moved on to fiddling with the ice machine.

“All right,” I say. He’s elbow-deep in ice. Maybe if he looked at me again I could see the amber flecks in his brown eyes, and maybe I could say something clever enough to make him smile again.

The horn blares and Reed raises an eyebrow.

I shake my head. “I guess I’m going home.”

Chapter 6

Mo

I’m going home.

I’m sitting in the dark, watching Annie hurry down the steps of Mr. Twister, but I’m not really here at all. I’m still at the kitchen table, staring at the steam curling off my tea, marveling at the perfect flatness of my dad’s voice. The way he said it—We’re going home—he could have been asking for more stew or telling me I needed a haircut.

I glance at the clock. It’s lying. It can’t have been just one hour. I’ve had a week’s worth of thoughts and a year’s worth of emotions since then, and yet I’ve landed at nothing—thinking nothing, feeling nothing. Is this what shock is? I can’t remember actually driving here, so it’s lucky I didn’t get pulled over for speeding since my autopilot mode is twenty over the limit.

He tried to make it sound like it was for the best, like the tanking of ReichartTek was not the end of the world.

My mother said nothing, of course. She just stared over my shoulder, out the French doors, through the pool chairs and the freshly painted fence, and into the blur of horizon and sunset. She already knew. That was clear. Her eyes were dry but bloodshot under swollen lids. More than once during his speech, she picked up the teapot with trembling hands, then realized nobody needed more tea and put it down again.

“It’s actually a good time to be going home,” he said after rambling about research opportunities in Jordan for someone of his education and experience.

“But this is home,” Sarina whispered. Then eyeing her nasty little cat, “Can I bring Duchess?”

At the time I was too dazed to be appropriately pissed off, but now I’m ready to punch the steering wheel. Can I bring Duchess? What kind of idiotic response is that? She’s fifteen—too old for her biggest concern in life to be proximity to her little cat. And as for But this is home, she has to see that it isn’t home. We’ve been pretending. Home claims you.

According to my passport, Jordan claims me, but by my third summer of visiting home, I knew I didn’t belong there anymore. Whatever admiration my Jordanian cousins had for my fancy American accent and clothes had turned sour by the time I was a teenager.

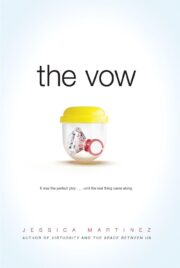

"The Vow" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Vow". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Vow" друзьям в соцсетях.