Like sun bursting through rain clouds, it hit her that loving Valentine Windham, being intimate with him, did not betray Francis. Francis would want her to find another love, to be happy and to be loved.

Love?

Abby looked a little concerned at Ellen’s expression. “Perhaps I should not have been quite so personal on the topic of grief.”

“Of course you should.” Ellen met Abby’s gaze in the mirror. “I am glad you were. It’s a topic nobody wants to bring up, and you can’t very well stroll up to the neighbors and tell them: I’m missing my spouse who has been gone for years, would you mind if I had a good cry on your shoulder?”

“We should be able to, but we don’t, do we?”

“I didn’t.” Ellen closed her eyes as Abby drew her hair in a slow sweep over both shoulders.

“Maybe you did, a little, just now. Let’s put you in the tub and wash this hair. As hot as the weather is, it will dry in no time.”

Ellen let Abby attend her, let her wash her hair, pour her a glass of wine while she soaked, and wrap her in a bath sheet when she was done. She hadn’t permitted herself this luxury—an attended bath—since Francis had died.

Punishing herself, perhaps? Or maybe just that much in need of bodily privacy.

“We can sit on the balcony and I’ll brush out your hair,” Abby said when Ellen was in her dressing gown, her hair hanging in damp curls.

And Abby went one better, having a tray of cheese and fruit brought up to go with the wine. They spent the time conversing about mutual neighbors, gardens, pie recipes, and the boys.

“They are splendid young men,” Ellen said after her second glass of wine—or was it her third? “And I think having them around makes us all less lonely.”

“Lonely,” Abby spat. “I got damned sick of being lonely. I’m not lonely now.”

“Because of Mr. Belmont. He is an impressive specimen.”

Abby grinned at her wineglass. “Quite, but so is your Mr. Windham.”

Ellen shook her head, and the countryside beyond the balcony swished around in her vision. “He isn’t my Mr. Windham.” It really was an interesting effect. “I think I’m getting tipsy.”

Abby nodded slowly. “One should, from time to time. Why isn’t he your Mr. Windham?”

“He’s far above my touch. I’m a gardener, for pity’s sake, and he’s a wealthy young fellow who will no doubt want children.”

Abby cocked her head. “You can still have children. You aren’t at your last prayers, Baroness.”

“I never carried a child to term for Francis,” Ellen said, some of the pleasant haze evaporating, “and I am… not fit for one of Mr. Windham’s station.”

Abby set her wine glass down. “What nonsense is this?”

Ellen should have remained silent; she should have let the moment pass with some unremarkable platitude, but five years of platitudes and silence—or perhaps half a bottle of wine—overwhelmed good sense.

“Oh, Abby, I’ve done things to be ashamed of, and they are such things as will not allow me to remarry. Ever.”

“Did you murder your husband?” Abby asked, her tone indignant. “Did you hold up stagecoaches on the high toby? Perhaps you sold secrets to the Corsican?”

“I did not murder my h-husband,” Ellen said, tears welling up again. “Oh, damn it all.” It was her worst, most scathing curse, and it hardly served to express one tenth of her misery. “What I did was worse than that, and I won’t speak of it. I’d like to be alone.”

Abby rose and put her arms around Ellen, enveloping her in a cloud of sweet, flowery fragrance. “Whatever you think you did, it can be forgiven by those who love you. I know this, Ellen.”

“I am not you,” Ellen said, her voice resolute. “I am me, and if I care for Mr. Windham, I will not involve him in my past.”

“You’re involving him in your present, though.” Abby sat back, regarding Ellen levelly. “And likely in your future, as well, I hope.”

“I should not,” Ellen said softly. “I should not, but you’re right, I have, and for the present I probably can’t help myself. He’ll tire of our dalliance, though, and then I’ll let him go, and all will be as it should be again.”

“You are not making sense. I don’t want to leave you here alone.”

“But you should,” Ellen said. “The gentlemen will be done with their baths and hungry for their luncheon. I’ll take a tray here, if you don’t mind.”

“I’ll leave you the cheese and fruit for now.” Abby got to her feet, her expression unconvinced. “Perhaps you’re done with the wine?”

“I think some tea is in order. You mustn’t take my dramatics too seriously.”

“I won’t. I’ll make your excuses to the fellows and send you up some reading with your luncheon.”

“My thanks.” Ellen let herself be hugged again. All three times she’d been pregnant, Ellen had felt the same wonderful, expansive affection for everyone in her world—well, almost everyone, as there was no genuine affection to be had for Freddy or some of his friends.

“Perhaps I’ll take a nap,” Ellen suggested.

“I never realized how invigorating a nap could be,” Abby replied, drawing back and picking up the wine bottle. “Not that kind of nap, though those are delightful, but simple rest. My first husband frowned upon it, unless one was sickening for something or suffering a migraine.”

“What a disappointing man he must have been, and what a lovely contrast Mr. Belmont must make.”

“Mr. Belmont encourages me to nap when I’m tired.” Abby’s smile was feline.

“Out.” Ellen pointed to the door, smiling back. “Out, out, out, and thank you for the visit, the wine, and the privacy.”

Though when Abby had left her alone, Ellen did not nap. Indeed, it took her some time to cease weeping.

Ten

“You had that look at luncheon you used to get when you’d been away from the piano too long,” St. Just remarked as he and Val grabbed the cribbage board, a blanket, and a small hamper.

“I am preoccupied,” Val said, “but not with a melody.” He wished he might be, rather than the disturbing things he’d overheard between Abby and Ellen as they’d visited on their balcony just the other side of the rose trellis adorning his own. What on earth could the Baroness Roxbury have done that was worse than murdering her husband?

“What’s the worst offense you could commit?” Val asked his brother as they rooted through Axel’s library cabinets for a deck of cards.

“Worst in the sense of violating my honor?” St. Just eyed Val curiously. “I suppose it would be betraying Winnie, who as a child is more helpless and dependent on me than is my countess.”

“They are both your property,” Val pointed out, spying a deck of cards. “Or as good as.”

“True, but Winnie is helpless, entrusted to me by no less than The Almighty in every regard. Her health, her happiness, her education, her spiritual well-being…”

“Daunting?” Val smiled in understanding.

“I have Emmie and Winnie to lean on. We shall contrive.”

“If you don’t have a son, what happens to the title?”

“Goes to Winnie’s eldest son, even if I do have a son with Emmie.”

Val met his brother’s eyes, not sure if the man were teasing. “Are you joking?”

“Dead serious,” St. Just replied as he waved his brother through the door of the library. “His Grace saw to the drafting of the letters patent and knew I didn’t want the earldom in the first place. As it stands, I will have the title for my lifetime, then my adopted daughter—our dear Bronwyn, who is in fact the former title holder’s offspring—will inherit on behalf of her heirs.”

“What did you have to give up to get this concession from Moreland?” Val asked as they gained the kitchen.

“I didn’t give up anything.” St. Just piled their booty on the counter and went to the bread box, extracting two fat muffins. “His Grace knew I never wanted an earldom—despite Her Grace’s insistence that one be imposed on me—and came up with this on his own. It’s a few words in the letters patent about my firstborn of any description rather than firstborn legitimate natural male son, and so on. Why do you find it so hard to believe the duke might act on decent notions?”

“He can.” Val made the admission easily. “He’s been more than decent to Anna, but his own ends are usually the ones he’s most inclined to serve.”

“His Grace becomes fixed on his goals.” St. Just wrapped the muffins in a clean dishcloth and tucked them in the hamper. “He’s a man who pursues his aims with an untiring fixity of purpose, regardless of the price it exacts from him in bodily comfort or personal ease. You hold this against him with a great deal of determination, I note.”

There was something irritatingly older-brother in St. Just’s observation, as if Val were missing some obvious point.

“I wouldn’t say I hold it against him so much.” Val frowned at the hamper. What was St. Just getting at? “The way he is just… frustrates. He’s more human since his heart seizure, and he’s made his peace with you and Gayle, but he and I have never had much in common.”

St. Just cocked his head, a curious smile on his lips. “Dear heart, what do you allow yourself to have in common with anybody? You stopped riding horses with me when you were little more than a boy; you’ve kept your businesses scrupulously away from Gayle’s eye; you seldom went out socializing with Bart or Victor, though you’ll escort our sisters all over creation; and you’ve chained yourself to that piano for most of your adult life.”

“I believe we’ve had this discussion. Would you be very offended if I begged off our cribbage match?” There was only so much fraternal cross-examination a man could politely bear, after all.

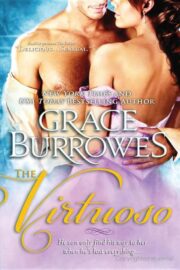

"The Virtuoso" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virtuoso". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virtuoso" друзьям в соцсетях.