Val shot off the bed and crossed to the door, pausing only long enough to tug on his boots.

“I’m sorry.” Darius rose and might have stopped him, but Val turned his back and got his hand on the door latch first. “I don’t like seeing you suffer, but were you really happy spending your entire life on the piano bench?”

“You think I’m happy now?” Val asked without turning.

He was down the stairs and out into the night without any sense of where he was headed or why movement might help. Darius was too damned perceptive by half, but really—an imaginary friend?

It was the kind of devastating observation older brothers might make of a younger sibling and then laugh about. Maybe, Val thought as his steps took him along a bridle path in the moonlit woods, this was why the artistic temperament was so unsteady. People not afflicted with the need to create could not understand what frustration of the urge felt like.

The weekend at Belmont’s loomed like an obstacle course in Val’s mind.

No finger exercises, no visiting friendly old repertoire to limber up, no reading open score to keep abreast of the symphonic literature, no letting themes and melodies wander around in his hands just to see what became of them. No glancing up and realizing he’d spent three hours on a single musical question and still gotten no closer to a satisfactory answer.

All of that, Val thought as he emerged from the darkened woods, was apparently never to be again. His hand was not getting better, though it wasn’t getting worse, either. It merely hurt and looked ugly and managed only activities requiring brute strength of the arm and not much real grip.

He found himself at the foot of Ellen FitzEngle’s garden and wondered if he could have navigated his way there on purpose. Her cottage was dark, but her back yard was redolent with all manner of enticing floral scents in the dewy evening air. If her gardens were pretty to the eye by day, they were gorgeous to the nose at night. Silently, Val wandered the rows until his steps took him to the back porch, where a fat orange cat strolled down the moonlit steps to strop itself against Val’s legs.

“He’s shameless.” Ellen’s voice floated through the shadows. “Can’t abide having to catch mice and never saw a cream bowl he couldn’t lick spotless in a minute.”

“What’s his name?” Val asked, not even questioning why Ellen would be alone on her porch after dark.

“Marmalade. Not very original.”

“Because he’s orange?” Val bent to pick the cat up and lowered himself to the top porch step.

“And sweet,” Ellen added, shifting from her porch swing to sit beside Val. “I take it you were too hot to sleep?”

“Too bothered. You?”

“Restless. You were right; change is unsettling to me.”

“I am unsettled, as well,” Val said, humor in his voice. “I seem to have a penchant for it.”

“Sometimes we can’t help what befalls us. What has you unsettled?”

Val was silent, realizing he was sitting beside one of very few people familiar with him who had never heard him play the piano. A woman who, in fact, didn’t even know he could play, much less that he was Moreland’s musical son.

“My hand hurts. It has been plaguing me for some time, and I’m out of patience with it.”

“Which hand?” Ellen asked, her voice conveying some surprise. Whatever trouble she might have expected Valentine Windham to admit, it apparently hadn’t been a simple physical ailment.

“This very hand here.” Val waved his left hand in the night air, going still when Ellen caught it in her own.

“Have you seen a physician?” she asked, tracing the bones on the back of his hand with her fingers.

“I did.” Val closed his eyes and gave himself up to the pleasure of her touch. Her fingers were cool and her exploration careful. “He assured me of nothing, save that I should treat it as an inflammation.”

“Which meant what?” Ellen’s fingers slipped over his palm. “That you should tote roofing slates about by the dozen? Carry buckets of mortar for your masons? I can feel some heat in it, now that you draw my attention to it.” She held his hand up to her cheek and cradled it against her jaw.

“It means I am to drink willow bark tea, which is vile stuff. I am to rest the hand, which I do by avoiding fine tasks with it. I am to use cold soaks, massage, and arnica, if it helps, and I am not to use laudanum, as that only masks symptoms, regardless of how much it still allows me to function.”

“I have considerable stores of willow bark tea.” Ellen drew her fingers down each of Val’s in turn. “And it sounds to me as if you’re generally ignoring sound medical advice.”

“I rub it. I rest it, compared to what I usually do with it. I don’t think it’s getting worse.”

“Stay here.” Ellen patted his hand and rose. She floated off into the cottage, leaving Val to marvel that if he weren’t mistaken, he was sitting in the darkness, more or less holding hands with a woman clad only in a summer nightgown and wrapper. Her hair was once again down, the single braid tidy for once where it hung along her spine.

Summer, even in the surrounds of Little Weldon, even with a half-useless sore hand, had its charms.

“Give me your hand,” Ellen said when she resumed her seat beside him. He passed over the requested appendage as he might have passed along a dish of overcooked asparagus. She rested the back of his hand against her thigh, and Val heard the sound of a tin being opened.

“You are going to quack me?”

“I am going to use some comfrey salve to help you comply with doctor’s orders. There’s probably arnica in it too.”

Val felt her spread something cool and moist over his hand, and then her fingers were working it into his skin. She was patient and thorough, smoothing her salve over his knuckles and fingers, into his palms, up over his wrist, and back down each finger. As she worked, he felt tension, frustration, and anger slipping down his arm and out the ends of his fingers, almost as if he were playing—

“You aren’t swearing,” Ellen said after she’d worked for some minutes in silence. “I have to hope I’m not hurting you.”

“You’re not.” Val’s tired brain took a moment to find even simple words. “It’s helping, or I think it is. Sometimes I go to bed believing I’ve had a good day with it; then I wake up the next day, and my hand is more sore than ever.”

“You should keep a journal,” Ellen suggested, slathering more salve on his hand. “That’s how I finally realized I’m prone to certain cyclical fluctuations in mood.”

He understood her allusion and considered were she not a widow—and were it not dark—she would not have ventured even that much.

“What did you say was in that salve?”

“Comfrey,” Ellen said, sounding relieved at the shift in topic. “Likely mint, as well, rosemary, and maybe some lavender, arnica if memory serves, a few other herbs, some for scent, some for comfort.”

“I like the scent,” Val said, wondering how long she’d hold his hand. It was childish of him, but he suspected the contact was soothing him as much as the specific ingredients.

“Is it helping?” Ellen asked, her fingers slowing again.

“It helps. I think the heat of your touch is as therapeutic as your salve.”

“It might well be.” Ellen sandwiched his larger hand between her smaller ones. “I do not hold myself out as any kind of herbalist. There’s too much guesswork and room for error involved.”

“But you made this salve.”

“For my own use.” Ellen kept his hand between hers. “I will sell scents, soaps, and sachets but not any product that could be mistaken for a medicine, tincture, or tisane.”

“Suppose it’s wise to know one’s limits.” Ellen was just holding Val’s hand in hers, and he was glad for the darkness, as his gratitude for the simple contact was probably plain on his face. “Ellen…”

She waited, holding his hand, and Val had to corral the words about to spill impulsively over his lips.

“You will accompany us to Candlewick tomorrow?” he asked instead.

“I will. I’ve made the acquaintance of the present Mrs. Belmont, and Mr. Belmont assured me she would welcome some female company.”

“And you, Ellen? Are you lonely for female company?”

“I am.” Val suspected it was an admission for her. “My mother was my closest friend, but she died shortly after my marriage. There is an ease in the companionship of one’s own gender, don’t you think?”

“Up to a point. One can be direct among one’s familiars, in any case, but you’ve brought me ease tonight, Ellen FitzEngle, and you are decidedly not the same gender as I.”

“We need not state the obvious.” Her voice was just a trifle frosty even as she kept her hands around Val’s.

“Do we need to talk about my kissing you a year ago? I’ve behaved myself for two weeks, Ellen, and hope by action I have reassured you where words would not.”

Silence or the summer evening equivalent of it, with crickets chirping, the occasional squeal of a passing bat, and the breeze riffling through the woods nearby.

“Ellen?”

Val withdrew his hand, which Ellen had been holding for some minutes, and slid his arm around her waist, urging her closer. “A woman gone silent unnerves a man. Talk to me, sweetheart. I would not offend you, but neither will I fare well continuing the pretense we are strangers.”

He felt the tension in her, the stiffness against his side, and regretted it. In the past two weeks, he’d all but convinced himself he was recalling a dream of her not a real kiss, and then he’d catch her smiling at Day and Phil or joking with Darius, and the clench in his vitals would assure him that kiss had been very, very real.

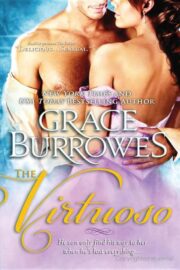

"The Virtuoso" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virtuoso". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virtuoso" друзьям в соцсетях.