He rose up as he grew chilled, and strolled along the tow path, westward toward the sun which slowly dropped in the sky and went from burning gold to embers as Robert walked, looking at the river but not seeing it, looking at the sky but not seeing it.

Who killed Amy?

Who gave her my ring?

The sun set and the sky grew palely gray; still Robert walked onward as if he did not own a stable full of horses, a stud of Barbary courses, a training program of young stallions, he walked like a poor man, like a man whose wife would give him a horse to ride.

Who killed Amy?

Who gave her my ring?

He tried not to remember the last time he had seen her, when he had left her with a curse, and turned her family against her. He tried not to remember that he had taken her in his arms and she in her folly had heard, and he in his folly had said: “I love you.”

He tried not to remember her at all because it seemed to him that if he remembered her he would sit down on the riverbank and weep like a child for the loss of her.

Who killed Amy?

Who gave her my ring?

If he thought, rather than remembered, he could avoid the wave of pain which was towering over him, ready to break. If he treated her death as a puzzle rather than a tragedy he could ask a question rather than accuse himself.

Two questions: Who killed Amy? Who gave her my ring?

When he stumbled and slipped and jolted himself to consciousness he realized that it had grown dark and he was walking blindly beside the steep bank of the deep, fast-flowing river. He turned then, a survivor from a family of survivors who had been wrong to marry a woman who did not share his inveterate lust for life.

Who killed Amy?

Who gave her my ring?

He started to walk back. It was only when he opened the iron gate to the walled garden that the coldness of his hand on the latch made him pause, made him realize that there were two questions: Who killed Amy? Who gave her my ring? but only one answer.

Whoever had the ring owned the symbol that Amy would trust. Amy would clear the house for a messenger who showed her that ring. Whoever had the ring was the person who killed her. There was only one person who could have done it, only one person who would have done it:

Elizabeth.

Robert’s first instinct was to go to her at once, to rage at her for the madness of her power. He could not blame her for wishing Amy gone; but the thought that his mistress could murder his wife, the girl he had married for love, filled him with anger. He wanted to take Elizabeth and shake the arrogance, the wicked, power-sated confidence out of her. That she should use her power as queen, her spy network, her remorseless will, against a target as vulnerable and as innocent as Amy, made him tremble like an angry boy at the strength of his feelings.

Robert did not sleep that night. He lay down on the bed and stared at the ceiling but over and over again he saw in his mind’s eye Amy receiving his ring, and running out to meet him, with his signet ring clenched in her little fist as her passport to the happiness she deserved. And then some man, one of Cecil’s hired killers no doubt, greeting her in his place, breaking her neck with one blow, a clenched fist to her ear, a rabbit chop to her neck, and catching her as she fell, carrying her back into the house.

Robert tortured himself with the thought of her suffering, of her moment of fear, perhaps of a moment of horror when she thought the killer came from him and the queen. That thought made him groan and turn over, burying his face in the pillow. If Amy had died thinking that he had sent an assassin against her then he did not see how he could bear to live.

The bedroom window lightened at last; it was dawn. Robert, as haggard as a man ten years his senior, rose to the window and looked out, his linen sheet wrapped around his naked body. It was going to be a beautiful day. The mist was curling slowly off the river and somewhere a woodpecker was drilling. Slowly the liquid melody of a song thrush started up like a benediction, like a reminder that life goes on.

I suppose I can forgive her, Robert thought. In her place, I might have done the same thing. I might have thought that our love came first, that our desire must be satisfied, come what may. If I had been her, I might have thought that we have to have a child, that the throne has to have an heir, and we dare not delay. If I had absolute power as she does I would probably have used it, as she has.

My father would have done it. My father would have forgiven her for doing it. Actually, he would have admired her decisiveness.

He sighed. “She did it for love of me,” he said aloud. “No other reason but to set me free so that she could love me openly. No other reason but that she could marry me, and I could be king. And she knows that we both want that more than anything in the world. I could accept this terrible sorrow and this terrible crime as a gift of love. I can forgive her. I can love her. I can draw some happiness out of this misery.”

The sky grew paler and then slowly the sun rose, pale primrose, over the silver of the river. “God forgive me and God forgive Elizabeth,” Robert prayed quietly. “And God bring Amy the peace in heaven which I denied her on earth. And God grant that I am a better husband this time.”

There was a tap at his chamber door. “It’s dawn, my lord!” the servant called out. “Do you want your hot water?”

“Yes!” Robert shouted back. He went to the door, trailing the sheet, and shot back the bolt from the inside. “Put it down there, lad. And tell them in the kitchen that I am hungry, and warn the stable that I will be there within the hour; I am leading out the hunt today.”

He was in the stable an hour before the court was ready to ride, making sure that everything was perfect: horses, hounds, tack, and hunt servants. The whole court was riding out today in merry mood. Robert stood on a vantage point of the steps above the stable and watched the courtiers mounting up, the ladies being helped into their saddles. His sister was not there. She had gone back to Penshurst.

Elizabeth was riding, in fine spirits. Robert went to help her into the saddle but then delayed, and let another man go. Over the courtier’s head she shot him a little tentative smile and he smiled back at her. She could be assured that things would be all right between them. She could be forgiven. The Spanish ambassador saw them off; the Hapsburg ambassador rode beside her.

They had a good morning’s hunting. The scent was strong and the hounds went well. Cecil rode out to meet them at dinner time when they were served with a picnic of hot soup and mulled ale and hot pasties under the trees which were a blaze of turning color: gold and red and yellow.

Robert stood away from the intimate circle around Elizabeth, even when she turned and gave him a shy little smile to invite him to her side. He bowed, but did not go closer. He wanted to wait until he could see her alone, when he could tell her that he knew what she had done, he knew that it had been for love of him, and that he could forgive her.

After they had dined and went to remount their horses, Sir Francis Knollys found his horse had been tied beside Robert’s mare.

“I must offer you my condolences on the death of your wife,” Sir Francis said stiffly.

“I thank you,” Robert replied, as coldly as the queen’s best friend had spoken to him.

Sir Francis turned his horse away.

“Do you remember an afternoon in the queen’s chapel?” Robert suddenly said. “The queen was there, me, you, and Lady Catherine. It was a binding service, remember? It was a promise that cannot be broken.”

The older man looked at him, almost with pity. “I don’t remember any such thing,” he said simply. “Either I did not witness it, or it did not happen. But I do not remember it.”

Robert felt himself flush with the heat of temper. “I remember it well enough; it happened,” he insisted.

“I think you will find you are the only one,” Sir Francis replied quietly and spurred on his horse.

Robert checked the horses over, and glanced at the hounds. One horse was limping slightly and he snapped his fingers for a groom to lead it back to the castle. He supervised the mounting of the court; but he hardly saw them. His head was pounding with the duplicity of Sir Francis, who would deny that Robert and the queen had sworn to marry, who was suggesting that the queen would deny it too. As if she would betray me, Robert swore to himself. After what she has done to be with me! What man could have more proof that a woman loves him than she would do such a thing to set me free? She loves me, as I love her, more than life itself! We were born for each other, born to be together. As if we could ever be apart! As if she did not do this terrible, this unbearable crime for love of me! To set me free!

“Are you glad to be back at court?” Cecil asked in a friendly tone, bringing his horse alongside Robert’s.

Robert, recalled to the present, looked at him. “I cannot say I am merry,” he said quietly. “I cannot say that my welcome has been warm.”

The secretary’s eyes were kind. “People will forget, you know,” he said gently. “It will never be the same again for you, but people forget.”

“And I am free to marry,” Dudley said. “When people have forgotten my wife, and her death, I will be free to marry again.”

Cecil nodded. “Indeed, yes. But not the queen.”

Dudley looked at him. “What?”

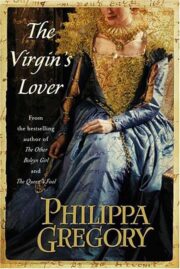

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.