“Why would she complain of me?” Elizabeth exclaimed. “How would she dare complain?”

“She was jealous,” he said fairly. “And she knew she had cause. And she did not receive very fair or generous treatment from me. I wanted her to grant me a divorce and I was unkind to her.”

“And now she is dead you are sorry, though you would have gone on being unkind to her in life,” she taunted him.

“Yes,” he said honestly. “I suppose all poor husbands would say the same: that they know they should be better than they are. But I feel wretched for her, today. I am glad to be a single man, of course. But I would not have wanted her dead. Poor innocent! No one would have wanted her dead.”

“You do not recommend yourself very well,” Elizabeth said archly, turning his attention to their courtship once more. “You do not sound like a good husband at all!”

For once Robert did not respond to her. He looked away, upriver to Cumnor, and his gaze was somber. “No,” he said. “I was not a good husband to her, and God knows, she was the sweetest and best wife a man could have had.”

There was a little stir among the waiting court, a messenger in the Dudley livery had entered the garden and paused at the fringe of the court. Dudley turned and saw the man and went toward him, his hand out for the proffered letter.

The watching courtiers saw Dudley take the letter, break the seal, open it, and saw him pale as he read the words.

Elizabeth went swiftly toward him and they parted to let her through. “What is it?” she demanded urgently. “Have a care! Everyone is watching you!”

“There is to be an inquest,” he said, his lips hardly moving, his voice no more than a breath. “Everyone is saying that it was no accident. They all think that Amy was murdered.”

Thomas Blount, Robert Dudley’s man, arrived at Cumnor Place the very day after Amy’s death, and examined all the servants one by one. Meticulously, he reported back to Robert Dudley that Amy had been known as a woman of erratic temper, sending everyone off to the fair on Sunday morning, though her companion Mrs. Oddingsell and Mrs. Forster had been unwilling to go.

“No need to mention that again,” Robert Dudley wrote back to him, thinking that he did not want his wife’s sanity questioned, when he knew he had driven her to despair.

Obediently, Thomas Blount never mentioned the matter of Amy’s odd behavior again. But he did say that Amy’s maid Mrs. Pirto had remarked that Amy had been in very great despair, praying for her own death on some occasions.

“No need to mention this, either,” Robert Dudley wrote back. “Is there to be an inquest? Can the men of Abingdon be trusted with such a sensitive matter?”

Thomas Blount, reading his master’s anxious scrawl well enough, replied that they were not prejudiced against the Dudleys in this part of the world, and that Mr. Forster’s reputation was good. There would be no jumping to any conclusion of murder; but of course, it must be what everyone thought. A woman does not die by falling down six stone steps, she does not die from a fall which does not disturb her hood or ruffle her skirts. Everyone thought that someone had broken her neck and left her on the floor. The facts pointed to murder.

“I am innocent,” Dudley said flatly to the queen in the Privy Council chamber at Windsor Castle, a daunting place to speak of such private things. “Good God, would I be such a sinner as to do such a deed to a virtuous wife? And if I did, would I be such a fool as to do it so clumsily? There must be a thousand better ways to kill a woman and make it appear an accident than break her neck and leave her at the foot of half a dozen stairs. I know those stairs; there is nothing to them. No one could break their neck falling down them. You could not even break your ankle. You would barely bruise. Would I tidy the skirts of a murdered woman? Would I pin her hood back on her head? Am I supposed to be an idiot as well as a criminal?”

Cecil was standing beside the queen. The two of them looked in silence at Dudley like unfriendly judges.

“I am sure the inquest will find out who did it,” Elizabeth said. “And your name will be cleared. But in the meantime, you will have to withdraw from court.”

“I will be ruined,” Dudley said blankly. “If you make me go, it looks as if you suspect me.”

“Of course I do not,” Elizabeth said. She glanced at Cecil. He nodded sympathetically. “We do not. But it is tradition that anyone accused of a crime has to withdraw from court. You know that as well as I.”

“I am not accused!” he said fiercely. “They are holding an inquest; they have not returned a verdict of murder. No one suggests that I murdered her!”

“Actually, everyone suggests that you murdered her,” Cecil helpfully pointed out.

“But if you send me from court you are showing that you think me guilty too!” Dudley spoke directly to Elizabeth. “I must stay at court, at your side, and then it will look as if I am innocent, and that you believe in my innocence.”

Cecil stepped forward half a step. “No,” he said gently. “There is going to be a most dreadful scandal, whatever verdict the inquest brings in. There is going to be a scandal which will rock Christendom, let alone this country. There is going to be a scandal which, if one breath of it touched the throne, would be enough to destroy the queen. You cannot be at her side. She cannot brazen out your innocence. The best thing we can all do is to behave as usual. You go to the Dairy House, withdraw into mourning, and await the verdict, and we will try to live down the gossip here.”

“There is always gossip!” Robert said despairingly. “We always ignored it before!”

“There has never been gossip like this,” Cecil said in very truth. “They are saying that you murdered your wife in cold blood, that you and the queen have a secret betrothal, and that you will announce it at your wife’s funeral. If the inquest finds you guilty of murder then many will think the queen your accomplice. Pray God you are not ruined, Sir Robert, and the queen destroyed with you.”

He was as white as the linen of his ruff. “I cannot be ruined by something I would never do,” he said through cold lips. “Whatever the temptation, I would never have done such a thing as to hurt Amy.”

“Then surely you have nothing to fear,” Cecil said smoothly. “And when they find her murderer, and he confesses, your name is cleared.”

“Walk with me,” Robert commanded his lover. “I must talk with you alone.”

“She cannot,” Cecil ruled. “She looks too guilty already. She can’t be seen whispering with a man suspected of murdering an innocent wife.”

Abruptly, Robert bowed to Elizabeth and left the room.

“Good God, Cecil, they won’t blame me, will they?” she demanded.

“Not if you are seen to distance yourself from him.”

“And if they find that she was murdered, and think that he did it?”

“Then he will have to stand trial, and if guilty, face execution.”

“He cannot die!” she exclaimed. “I cannot live without him. You know I cannot live without him! All this will be a disaster if it comes to that.”

“You could always give him a pardon,” he said calmly. “If it comes to that. But it won’t. I can assure you, they will not find him guilty. I doubt that there is any evidence to link him to the crime, except his own indiscretion and the general belief that he wanted his wife dead.”

“He looked heartbroken,” she said pitifully.

“He did indeed. He will take it hard; he is a very proud man.”

“I cannot bear that he should be so distressed.”

“It cannot be helped,” Cecil said cheerfully. “Whatever happens next, whatever the inquest rules, his pride will be thrown down and he will always be known as the man who broke his wife’s neck in the vain attempt to be king.”

At Abingdon the jury was sworn in and started to hear the evidence about the death of Lady Amy Dudley. They heard that she insisted on everyone going to the fair so that she was left alone in the house. They heard that she was found dead at the foot of the small flight of stairs. The servants attested that her hood was tidy on her head, and her skirts pulled down, before they had picked her up and carried her to her bed.

In the pretty Dairy House at Kew, Robert ordered his mourning clothes but could hardly bear to stand still as the man fitted them.

“Where is Jones?” he demanded. “He is much quicker than this.”

“Mr. Jones couldn’t come.” The man sat back on his heels and spoke, his mouth full of pins. “He said to send you his apologies. I am his assistant.”

“My tailor did not come when I sent for him?” Robert repeated, as if he could not believe the words. “My own tailor refused to serve me?” Dear God, they must think me halfway to the Tower again; if not even my tailor is troubled for my custom, then they must think me halfway to the scaffold for murder.

“Sir, please let me pin this,” the man said.

“Leave it,” Robert said irritably. “Take another coat, an old coat, and make it to the same pattern. I cannot bear to stand and have you pin that damned crow color all over me. And you can tell Jones that when I next need a dozen new suits I shall remember that he did not attend me today.”

Impatiently, he threw off the half-fitted jacket and strode across the little room in two strides.

Two days and not a word from her, he thought. She must think I did it. She must think me so wicked as to do such a thing. She must think me a man who would murder an innocent wife. Why would she want to marry such a man? And all the time there will be those very quick to assure her that it is just the sort of man I am.

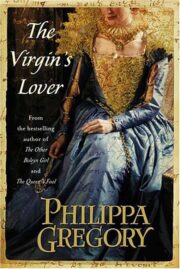

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.