Young Robert Dudley had been running in and out of the halls of the royal palaces of England as his home, while Elizabeth had been in disgrace, alone in the country. Of the three of them it was Dudley who was most accustomed to power and position. Cecil glanced at the young queen and saw, mirrored in her face, his own uncertainty and sense of inadequacy.

“Robert, I don’t know how to do this,” she said in a small voice. “I can’t even remember how to get from the king’s rooms to the great hall. If someone doesn’t walk before me I’ll get lost. I don’t know how to get to the gardens from the picture gallery, or from the stable to my rooms, I…I’m lost here.”

Cecil saw, he could not be mistaken, the sudden leap of something in the younger man’s face—hope? ambition?—as Dudley realized why the young queen and her principal advisor were standing outside her premier London palace, looking almost as if they did not dare to go in.

Sweetly, he offered her his arm. “Your Majesty, let me welcome you to my old home, your new palace. These walks and these walls will be as familiar to you as Hatfield was, and you will be happier here than you have ever been before, I guarantee it. Everyone gets lost in Whitehall Palace; it is a village, not a house. Let me be your guide.”

It was generously and elegantly done, and Elizabeth’s face warmed. She took his arm and glanced back at Cecil.

“I will follow, Your Grace,” he said quickly, thinking that he could not bear to have Robert Dudley show him his own rooms as if he owned the place. Aye, Cecil thought. Go on, take your advantage. You just had the two of us at a loss. We stood here, the newcomers, not even knowing where our bedrooms are; and you know this place like the back of your hand. It’s as if you are more royal than her, as if you were the rightful prince here, and now, graciously enough, you show her round your home.

But it was not all as easy as Elizabeth learning her way round the corridors and back stairs of the warren that was Whitehall Palace. When they went out in the streets there were many who doffed their caps and cried hurrah for the Protestant princess, but there were many also who did not want another woman on the throne, seeing what the last one had done. Many would have preferred Elizabeth to declare her betrothal to a good Protestant prince and get a sensible man’s hand on the reins of England at once. There were many others who remarked that surely Lord Henry Hastings, nephew to King Henry, and married to Robert Dudley’s sister, had nearly as good a claim as Elizabeth, and he was an honorable young man and fit to rule. There were even more who whispered in secret or said nothing at all but who longed for the coming of Mary, Queen of Scots and Princess of France, who would bring peace to the kingdom, a lasting alliance with France, and an end to religious change. She was younger than Elizabeth, for sure, a sixteen-year-old girl but a real little beauty, and married to the heir to the French throne with all that power behind her.

Elizabeth, new-come to her throne, not yet crowned or anointed, had to find her way round her palace, had to put her friends in high places and that quickly, had to act like a confident Tudor heir, and had somehow to deal at once with her church which was in open and determined opposition to her and which would, unless it was swiftly controlled, bring her down.

There had to be a compromise and the Privy Council, still staffed with Mary’s advisors but leavened by Elizabeth’s new friends, came up with it. The church was to be restored to the condition in which Henry VIII had left it at the time of his death. An English church, commanded by Englishmen and headed by the monarch, that obeyed English laws and paid its tithes into the English treasury, where the litany, homilies, and prayers were often read in English; but where the shape and content of the service were all but identical to the Catholic Mass.

It made sense to everyone who was desperate to see Elizabeth take the throne without the horror of a civil war. It made sense to everyone who longed for a peaceful transition of power. Indeed, it made sense to everyone but to the church itself, whose bishops would not countenance one step toward the mortal heresy of Protestantism, and, worst of all, it made no sense to the queen, who was suddenly, at this inopportune moment, stubborn.

“I won’t have the Host raised in the Royal Chapel,” Elizabeth specified for the twentieth time. “When we have Christmas Mass, I will not have the Host raised as an object of worship.”

“Absolutely not,” Cecil agreed wearily. It was Christmas Eve and he had been hoping that he might have got to his own home for Christmas. He had been thinking, rather fondly, that he might have been there to take Christmas communion in his own chapel, the Protestant way, without drama, as God had intended it, and then stayed with his family for the rest of the days of Christmas, returning to court only for the great feast of present-giving on Twelfth Night.

It had been a struggle to find a bishop who would celebrate Mass in the Royal Chapel before the Protestant princess at all, and now Elizabeth was trying to rewrite the service.

“He will let the congregation take communion?” she confirmed. “Whatever his name is? Bishop Oglesham?”

“Owen Oglethorpe,” Cecil corrected her. “Bishop of Carlisle. Yes, he understands your feelings. Everything will be done as you wish. He will serve at the Christmas Mass in your chapel, and he won’t elevate the Host.”

Next day, Cecil cradled his head once more as the bishop defiantly held the pyx above his head for the congregation to worship the body of Christ at the magical moment of transubstantiation.

A clear voice rang out from the royal pew. “Bishop! Lower the pyx.”

It was as if he had not heard her. Indeed, since his eyes were closed and his lips moving in prayer, perhaps he had not heard her. The bishop believed with all his heart that God was coming down to earth, that he held the real presence of the living God between his hands, that he was holding it up for the faithful to worship, as they must, as faithful Christians, do.

“Bishop! I said, Bishop! Lower that pyx.”

The wooden fretwork shutter of the royal pew banged open like a thunderclap. Bishop Oglethorpe turned slightly from the altar, and glanced over his shoulder to meet the furious gaze of his queen, leaning out from the royal pew like a fishwife over a market stall, her cheeks flaming red with temper, her eyes black as an angry cat’s. He took in her stance—up from her knees, standing at her full height, her finger pointing at him, her voice commanding.

“This is my own chapel. You are serving as my chaplain. I am the queen. You will do as I order. Lower that pyx.”

As if she did not matter at all, he turned back to the altar, closed his eyes again, and gave himself up to his God.

He felt, as much as he heard, the swish of her gown as she strode out of the door of the pew and the bang as she slammed it shut, like a child running from a room in temper. His shoulders prickled, his arms burned; but still he kept his back resolutely turned to the congregation, celebrating the Mass not with them, but for them: a process private between the priest and his God, which the faithful might observe, but could not join. The bishop put the pyx gently down on the altar and folded his hands together in the gesture for prayer, secretly pressing them hard against his thudding heart, as the queen stormed from her own chapel, on Christmas Day, driven from the place of God on His very day, by her own muddled, heretical thinking.

Two days later, Cecil, still not home for Christmas, faced with a royal temper tantrum on one hand and a stubborn bishop on the other, was forced to issue a royal proclamation that the litany, Lord’s Prayer, lessons, and the ten commandments would all be read in English, in every church of the land, and the Host would not be raised. This was the new law of the land. Elizabeth had declared war on her church before she was even crowned.

“So who is going to crown her?” Dudley asked him. It was the day before Twelfth Night. Neither Cecil nor Dudley had yet managed to get home to their wives for so much as a single night during the Christmas season.

Does he not have enough to do in planning the Twelfth Night feast, that now he must devise religious policy? Cecil demanded of himself irritably, as he got down from his horse in the stable yard and tossed the reins to a waiting groom. He saw Dudley’s eyes run over the animal and felt a second pang of irritation at the knowledge that the younger man would see at once that it was too short in the back.

“I thank you for your concern but why do you wish to know, Sir Robert?” The politeness of Cecil’s tone almost took the ice from his reply.

Dudley’s smile was placatory. “Because she will worry, and this is a woman who is capable of worrying herself sick. She will ask me for my advice, and I want to be able to reassure her. You’ll have a plan, sir, you always do. I am only asking you what it is. You can tell me to mind my horses and leave policy to you, if you wish. But if you want her mind at rest you should tell me what answer I should give her. You know she will consult me.”

Cecil sighed. “No one has offered to crown her,” he said heavily. “And between you and me, no one will crown her. They are all opposed, I swear that they are in collusion. I cannot trace a conspiracy but they all know that if they do not crown her, she is not queen. They think they can force her to restore the Mass. It’s a desperate position. The Queen of England, and not one bishop recognizes her! Winchester is under house arrest for his sermon at the late queen’s funeral, Oglethorpe in all but the same case for his ridiculous defiance on Christmas Day. He says he will go to the stake before he gives way to her. She wouldn’t let Bishop Bonner so much as touch her hand when she came into London, so he is her sworn enemy too. The Archbishop of York told her to her face that he regards her as a heretic damned. She’s got the Bishop of Chichester under house arrest, although he is sick as a dog. They are all unanimously against her, not a shadow of doubt among them. Not even a tiny crack where one might seed division.”

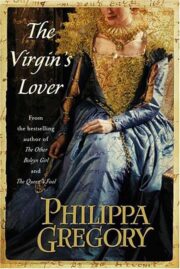

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.