Madwoman! he swore at it, though still he did not say a word out loud. Feckless, vain, extravagant, willful woman. God help me that I ever thought you the savior of your country. God help me that I ever put my skills at your crazed service when I would have been better off planting my own garden at Burghley and never dancing attendance at your mad, vain court.

He raged for a few moments more, walking backward and forward before the balled-up letter, discarded in the knot garden, then, because documents were both a treasure and a danger, he stepped over the little hedge and retrieved it, smoothed it out, and reread it.

Then he saw two things that he had missed at the first reading. Firstly the date. She had dated it the third of July but it had arrived five days after the treaty had been signed and peace proclaimed. It had taken far too long to arrive. It had taken double the journey time. It had come too late to influence events. Cecil turned for his messenger.

“Ho! Lud!”

“Yes, Sir William?”

“Why did this take six days to reach me? It is dated the third. It should have been here three days ago.”

“It was the queen’s own wish, sir. She said she did not want you troubled with the letter until your business had been done. She told me to leave London and go into hiding for three days, to give the impression to the court that I had set out at once. It was her order, sir. I hope I did right.”

“Of course you did right in obeying the queen,” Cecil growled.

“She said she did not want you distracted by this letter,” the man volunteered. “She said she wanted it to arrive when your work was completed.”

Thoughtfully, Cecil nodded the man away.

What? he demanded of the night sky. What, in the devil’s name, what?

The night sky made no reply, a small cloud drifted by like a gray veil.

Think, Cecil commanded himself. In the afternoon, say; in the evening, say; in a temper, she makes a great demand of me. She has done that before, God knows. She wants everything: Calais, her arms restored to her sole use, peace, and five hundred thousand crowns. Badly advised (by that idiot Dudley for example) she could think all that possible, all that her due. But she is no fool, she has a second thought, she knows she is in the wrong. But she has sworn before witnesses that she will ask for all these things. So she writes the letter she promises them, signs and seals it before them but secretly she delays it on the road, she makes sure that I do the business, that peace is achieved, before she lays an impossible demand upon me.

So she has made an unreasonable demand, and I have done a great piece of work and we have both done what we should do. Queen and servant, madam and man. And then, to make sure that her interfering gesture is nothing more than an interfering gesture, without issue: she says that if her letter arrives too late (and she has ensured that it will arrive too late) I may disregard her instructions.

He sighed. Well and good. And I have done my duty, and she has done her pleasure, and no harm is done to the peace except my joy in it, and my anticipation that she would be most glad, most grateful to me, is quite gone.

Cecil tucked her letter into the pocket inside his jacket. Not a generous mistress, he said quietly to himself. Or at any rate not to me, though clearly she will write a letter and delay it and lie about it to please another. There is not a king in Christendom or in the infidel lands who has a better servant than I have been to her, and she rewards me with this… This trap.

Not really like her, he grumbled quietly to himself, walking toward the steps to the castle doorway. An ungenerous spirit, to distress me so at the moment of my triumph, and she is not usually ungenerous. He paused. But perhaps badly advised.

He paused again. Robert Dudley, he remarked confidentially to the steps as he set his well-shined shoe on the first paving stone. Robert Dudley, I would wager my life on it. Begrudging my success, and wishing to diminish it in her eyes. Wanting more, always more than can reasonably be granted. Ordering her to write a letter filled with impossible demand and then she writing it to please him but delaying it so as to save the peace. He paused once more. A foolish woman to take such a risk to please a man, he concluded.

Then he paused in his progress again as the worst thought came to him. But why would she let him go so far as to dictate her letters to me, on the greatest matter of policy we have ever faced? When he is not even a member of the Privy Council? When he is nothing but her Master of Horse? While I have been so far away, what advantages has he taken? What progress has he made? Dear God, what power does he have over her now?

Cecil’s letter proclaiming the peace of Scotland was greeted by Elizabeth’s court, led by Robert, with sour thanksgiving. It was good, but it was not good enough, Robert implied; and the court, with one eye on the queen and the other on her favorite, concurred.

The leading members of the Privy Council grumbled among themselves that Cecil had done a remarkable job and looked to have small thanks for it. “A month ago and she would have fallen on his neck if he could have got peace after only three months’ war,” Throckmorton said sourly. “She would have made him an earl for getting peace within six weeks. Now he has done it within a day of getting to Edinburgh and she has no thanks for him. That’s women for you.”

“It’s not the woman who is ungrateful, it is her lover,” Sir Nicholas Bacon said roundly. “But who will tell her? And who will challenge him?”

There was a complete silence.

“Not I, at any rate,” Sir Nicholas said comfortably. “Cecil will have to find a solution to this when he comes home. For surely to God, matters cannot go on like this for very much longer. It is a scandal, which is bad enough, but it leaves her as something and nothing. Neither wife nor maid. How is she to get a son when the only man she sees is Robert Dudley?”

“Perhaps she’ll get Dudley’s son,” someone said quietly at the back.

Someone swore at the suggestion; another man rose up abruptly and quitted the room.

“She will lose her throne,” another man said firmly. “The country won’t have him, the Lords won’t have him, the Commons won’t have him, and d’you know, my lords, I damned well won’t have him.”

There was a swift mutter of agreement, then someone said warningly, “This is near to treason.”

“No, it isn’t,” Francis Bacon insisted. “All anyone has ever said is that they wouldn’t accept Dudley as king. Well and good. There’s no treason in that since he will never be king, there is no possibility of it in our minds. And Cecil will have to come home to see how to make sure there is no possibility of it in his mind too.”

The man who knew himself to be King of England in all but name was in the stable yard inspecting the queen’s hunter. She had ridden so little that the horse had been exercised by a groom and Dudley wanted to be sure that the lad was as gentle on the horse’s valuable mouth as he would have been himself. While he softly pulled the horse’s ears and felt the velvet of her mouth Thomas Blount came up behind him and quietly greeted him. “Good morning, sir.”

“Good morning, Blount,” Robert said quietly.

“Something odd I thought you should know.”

“Yes?” Robert did not turn his head. No one looking at the two men would have thought they were concerned with anything but horse care.

“I came across a shipment of gold last night, smuggled in from the Spanish, shipped by Sir Thomas Gresham of Antwerp.”

“Gresham?” Dudley asked, surprised.

“His servant on board, bristling with knives, sick with worry,” Blount described.

“Gold for who?”

“For the treasury,” Blount said. “Small coins, bullion, all shapes and sizes. My man, who helped unload, said there was word that it was for minting into new coin, to pay the troops. I thought you might like to know. It was about three thousand pounds’ worth, and there has been more before and will be more next week.”

“I do like to know,” Robert confirmed. “Knowledge is coin.”

“Then I hope the coin is Gresham’s gold,” Blount quipped. “And not the dross I have in my pocket.”

Half a dozen thoughts snapped into Robert’s head at once. He spoke none of them. “Thank you,” he said. “And let me know when Cecil starts his journey home.”

He left the horse with the groom and went to find Elizabeth. She was not yet dressed; she was seated at the window in her privy chamber with a wrap around her shoulders. When Robert came in Blanche Parry looked up at him with relief. “Her Grace won’t dress though the Spanish envoy wants to see her,” she said. “Says she is too tired.”

“Leave us,” Robert said shortly and waited while the women and the maids left the room.

Elizabeth turned and smiled at him and took his hand and held it to her cheek. “My Robert.”

“Tell me, my pretty love,” Robert said quietly. “Why are you bringing in boatloads of Spanish gold from Antwerp, and how are you paying for it all?”

She gave a little gasp and the color went from her face, the smile from her eyes. “Oh,” she said. “That.”

“Yes,” he replied evenly. “That. Don’t you think you had better tell me what is going on?”

“How did you find out? It is supposed to be a great secret.”

“Never mind,” he said. “But I am sorry to learn that you still keep secrets from me, after your promises, even though we are husband and wife.”

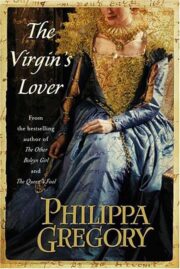

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.