“We should have it back,” Robert said stubbornly. “I lost a brother at St. Quentin; I nearly lost my own life before the walls of Calais. The blood of good Englishmen went into that canal, the canal that we dug and fortified. It is as much an English town as Leicester. We should have it back.”

“Oh, Robert…”

“We should,” he insisted. “If he has settled for anything less, then he has done us a great disservice. And I shall tell him so. And, what is more, if we do not have Calais, then he has not secured a lasting peace, since we will have to go to war for it as soon as the men are home from Scotland.”

“He knows that Calais matters to us,” she said weakly. “But we would not go to war for it…”

“Matters!” Robert slammed his fist on the river wall. “Calais matters as much as Leith Castle, perhaps more. And your coat of arms, Elizabeth! The Queen of France has to give up quartering our arms on her shield. And they should pay us.”

“Pay?” she asked, suddenly attending.

“Of course,” he said. “They have been the aggressor. They should pay us for forcing us to defend Scotland. We have emptied the treasury of England to defend against them. They should compensate us for that.”

“They never would. Would they?”

“Why not?” he demanded. “They know that they are in the wrong. Cecil is bringing them to a settlement. He has them on the run. This is the time to hit them hard, while we have them at a disadvantage. He must gain us Scotland, Calais, our arms, and a fine.”

Elizabeth caught his mood of certainty. “We could do this!”

“We must do this,” he confirmed. “Why go to war if not to win? Why make peace if not to gain the spoils of war? Nobody goes to war just to defend, they go to make things better. Your father knew that, he never came away from a peace without a profit. You must do the same.”

“I shall write to him tomorrow,” she decided.

“Write now,” Robert said. “He has to get the letter at once, before he signs away your rights.”

For a moment she hesitated.

“Write now,” he repeated. “It will take three days to get there at the fastest. You must get it to him before he completes the treaty. Write while it is fresh in our minds, and then the business of state is finished and we can be ourselves again.”

“Ourselves?” she asked with a little smile.

“We are newly wed,” he reminded her softly. “Write your proclamation, my queen, and then come to your husband.”

She glowed with pleasure at his words and together they turned back to Whitehall Palace. He led her through the court to her rooms and stood behind her as she sat at her writing table, and raised her pen. “What should I write?”

She waits to write to my dictation, Robert rejoiced silently to himself. The Queen of England writes my words, just as her brother took my father’s dictation. Thank God this day has come, and come through love.

“Write in your own words, as you would usually write to him,” he recommended. The last thing I want is for him to hear my voice in her letter. “Just tell him that you demand that the French leave Scotland, you demand the return of Calais, the surrender of your coat of arms, and a fine.”

She bowed her bronze head and wrote. “How much of a fine?”

“Five hundred thousand crowns,” he said, picking the number at random.

Elizabeth’s head jolted up. “They would never pay that!”

“Of course they won’t. They will pay the first installment perhaps and then cheat on the rest. But it tells them the price we set on their interference with our kingdoms. It tells them that we value ourselves highly.”

She nodded. “But what if they refuse?”

“Then tell him he is to break the negotiations off and go to war,” Robert declared. “But they won’t refuse. Cecil will win them to this agreement if he knows you are determined. This is a signal to him to come home with a great prize, and a signal to the French that they dare not meddle with our affairs again.”

She nodded and signed it with a flourish. “I will send it this afternoon,” she said.

“Send it now,” he ordered. “Time is of the essence. He has to have this before he concedes any of our demands.”

For a moment she hesitated. “As you wish.”

She turned to Laetitia. “Send one of the maids for one of the Lord Secretary’s messengers,” she said. She turned back to Robert. “As soon as I have sent this, I should like to go riding.”

“Is it not too hot for you?”

“Not if we go straightaway. I feel as if I have been cooped up here in Whitehall for a lifetime.”

“Shall I have them saddle the new mare?”

“Oh, yes!” she said, pleased. “I shall meet you at the stables, as soon as I have sent this.”

He watched her sign and seal it and only then did he bow, kiss her hand, and saunter to the door. The courtiers parted before him, doffing their caps, many bowed. Robert walked like a king from the room and Elizabeth watched him leave.

The girl came down the gallery with the messenger following her, and brought him to Elizabeth, where she stood watching Robert stroll away. As he drew near, Elizabeth turned into a window bay, the sealed letter in her hand, and spoke to him so quietly that no one else could hear.

“I want you to take this letter to your master in Edinburgh,” she said quietly. “But you are not to start today.”

“No? Your Grace?”

“Nor tomorrow. But take it the day after. I want the letter delayed by at least three days. Do you understand?”

He bowed. “As you wish, Your Grace.”

“You will tell everyone, very loudly and clearly, that you are setting off at once with a message for Sir William Cecil, and that he should have it the day after tomorrow since you can now get letters to Edinburgh within three days.”

He nodded; he had been in Cecil’s service too long to be surprised at any double dealing. “Shall I leave London as if I were going at once, and hide on the road?”

“That’s right.”

“What day do you want him to have it?”

The queen thought for a moment. “What is today? The third? Put it into his hands on July the ninth.”

The servant tucked the letter in his doublet and bowed. “Shall I tell my master that it was delayed?”

“You can do. It won’t matter by then. I don’t want him distracted from his work by this letter. His work will be completed by then, I hope.”

Edinburgh

July 4th 1560 To the queen The queen regent is dead but the siege is still holding, though the spirit has gone out of them.

I have found a form of words which they can agree: it is that the French king and queen will grant freedom to the Scots as a gift, as a result of your intercession as a sister monarch, and remove their troops. So we have won everything we wanted at the very last moment and by the merciful intercession of God.

This will be the greatest victory of your reign and the foundation of the peace and strength of the united kingdoms of this island. It has broken the Auld Alliance between France and Scotland forever. It has identified you as the protector of Protestantism. I am more relieved and happy than I have ever been in my life.

God bless you and your seed, for neither peace nor war without this will profit us long, William Cecil, dated this day, the fourth of July, in Edinburgh Castle, 1560.

Cecil, having averted war, broken the alliance of the French with the Scots, and identified Elizabeth as Europe’s newest and most daring power player, was walking in the cool of the evening in the little garden of Edinburgh castle and admiring the planting of the small bay trees and the intricate patterns of the colored stones.

His servant hesitated at the top of the steps, trying to see his master in the dusk. Cecil raised his hand and the man came toward him.

“A letter from Her Majesty.”

Cecil nodded and took it, but did not open it at once. She knew he was near to settlement, this would be a letter thanking him for his services, promising him her love and his reward. She knew, as no one else knew, that England had been on a knife edge of disaster with this war in Scotland. She knew, as no one else knew, that no one could have won them a peace but Cecil.

Cecil sat on the garden bench and looked up at the great gray walls of the castle, at the swooping bats, at the early stars coming out, and knew himself to be content. Then he opened his letter from the queen.

For a moment he sat quite still, reading the letter, and then rereading it over and over again. She has run mad, was his first thought. She has run mad with the worry and distress of this war and now she has gone as war-hungry as she was fearful before. Good God, how can a man make any sense of his life when he is working for a woman who can blow hot and cold in a second, never mind in a day.

Good God, how can a man make a lasting peace, an honorable peace, when the monarch can suddenly call for extra settlement after the treaty has been signed? The return of Calais? The coat of arms? And now a fine? Why not ask for the stars in the sky? Why not ask for the moon?

And what is this, at the end of the letter? To break off negotiations if these objects cannot be achieved? And, in God’s name: do what? Make war with a bankrupt army, with the heat of summer coming? Let the French recall their troops to battle stations, who are even now packing to leave?

Cecil scrunched the queen’s letter into a ball, dropped it to the ground, and kicked it as hard as he could, over the tiny ornamental hedge into the center of the knot garden.

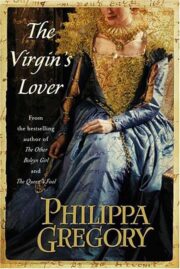

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.