Elizabeth’s radiant smile warmed her face. “We’ll have so much to talk about when I see her!”

“We will have to clear the court so that you two can chatter,” Dudley said. “I remember Catherine when we had ‘Be Silent” tournaments. D’you remember? She always lost.”

“And she always blinked first when we had a staring joust.”

“Except for that time when Ambrose put his mouse in her sewing bag. Then she screamed the house down.”

“I miss her,” Elizabeth said simply. “She is almost all the family I have.”

Neither of the men reminded her of her flint-hearted Howard relations who had all but disowned her when she was disgraced, and now were swarming around her emerging court claiming her as their own once more.

“You have me,” Robert said gently. “And my sister could not love you more if she were your own.”

“But Catherine will scold me for my crucifix and the candles in the Royal Chapel,” Elizabeth said sulkily, returning to the uppermost difficulty.

“How you choose to worship in the Royal Chapel is not her choice,” Cecil reminded her. “It is yours.”

“No, but she chose to leave England rather than live under the Pope, and now that she and all the other Protestants are coming home, they will be expecting a reformed country.”

“As do we all, I am sure.”

Robert Dudley threw a quizzical look at him as if to suggest that not everyone shared Cecil’s clarity of vision. Blandly, the older man ignored him. Cecil had been a faithful Protestant since the earliest days and had suffered years of neglect from the Catholic court because of his loyalty to his faith and his service of the Protestant princess. Before that, he had served the great Protestant lords, the Dudleys themselves, and advised Robert’s father on the advance of the Reformation. Robert and Cecil were old allies, if never friends.

“There is nothing Papist about a crucifix on the altar,” Elizabeth specified. “They cannot object to that.”

Cecil smiled indulgently. Elizabeth loved jewels and gold in church, the priests in their vestments, embroidered altar cloths, bright colors on the walls, candles and all the panoply of the Catholic faith. But he was confident that he could keep her in the reformed church that was her first and earliest practice.

“I will not tolerate the raising of the Host and worshipping it as if it were God Himself,” she said firmly. “That is Popish idolatry indeed. I won’t have it, Cecil. I won’t have it done before me and I won’t have it held up to confuse and mislead my people. It is a sin, I know it. It is a graven idol, it is bearing false witness; I cannot tolerate it.”

He nodded. Half the country would agree with her. Unfortunately the other half would as passionately disagree. To them the communion wafer was the living God and should be worshipped as a true presence; to do anything less was a foul heresy that only last week would have been punishable by death by burning.

“So, who have you found to preach at Queen Mary’s funeral?” she asked suddenly.

“The Bishop of Winchester, John White,” he said. “He wanted to do it, he loved her dearly, and he is well regarded.” He hesitated. “Any one of them would have done it. The whole church was devoted to her.”

“They had to be,” Robert rejoined. “They were appointed by her for their Catholic sympathies; she gave them a license to persecute. They won’t welcome a Protestant princess. But they’ll have to learn.”

Cecil only bowed, diplomatically saying nothing, but painfully aware that the church was determined to hold its faith against any reforms proposed by the Protestant princess, and half the country would support it. The battle of the Supreme Church against the young queen was one that he hoped to avoid.

“Let Winchester do the funeral sermon then,” she said. “But make sure he is reminded that he must be temperate. I want nothing said to stir people up. Let’s keep the peace before we reform it, Cecil.”

“He’s a convinced Roman Catholic,” Robert reminded her. “His views are known well enough, whether he speaks them out loud or not.”

She rounded on him. “Then if you know so much, get me someone else!”

Dudley shrugged and was silent.

“That’s the very heart of it,” Cecil said gently to her. “There is no one else. They’re all convinced Roman Catholics. They’re all ordained Roman Catholic bishops, they’ve been burning Protestants for heresy for the last five years. Half of them would find your beliefs heretical. They can’t change overnight.”

She kept her temper with difficulty but Dudley knew she was fighting the desire to stamp her foot and stride away.

“No one wants anyone to change anything overnight,” she said finally. “All I want is for them to do the job to which God has called them, as the old queen did hers by her lights, and as I will do mine.”

“I will warn the bishop to be discreet,” Cecil said pessimistically. “But I cannot order him what to say from his own pulpit.”

“Then you had better learn to do so,” she said ungraciously. “I won’t have my own church making trouble for me.”

“‘I praised the dead more than the living,’” the Bishop of Winchester started, his voice booming out with unambiguous defiance. “That is my text for today, for this tragic day, the funeral day of our great Queen Mary. ‘I praised the dead more than the living.’ Now, what are we to learn from this: God’s own word? Surely, a living dog is better than a dead lion? Or is the lion, even in death, still more noble, still a higher being than the most spritely, the most engaging young mongrel puppy?”

Leaning forward in his closed pew, mercifully concealed from the rest of the astounded congregation, William Cecil groaned softly, dropped his head into his hands, and listened with his eyes closed as the Bishop of Winchester preached himself into house arrest.

Winter 1558–59

THE COURT ALWAYS HELD CHRISTMAS at Whitehall Palace, and Cecil and Elizabeth were anxious that the traditions of Tudor rule should be seen as continuous. The people should see that Elizabeth was a monarch just as Mary had been, just as Edward had been, just as their father had been: the glorious Henry VIII.

“I know there should be a Lord of Misrule,” Cecil said uncertainly. “And a Christmas masque, and there should be the king’s choristers, and a series of banquets.” He broke off. He had been a senior administrator to the Dudley family and thus served their masters the Tudors; but he had never been part of the inner circle of the Tudor court. He had been present at business meetings, reporting to the Dudley household, not at entertainments, and he had never taken part in any of the organization or planning of a great court.

“I last came to Edward’s court when he was sick,” Elizabeth said, worried. “There was no feasting or masquing then. And Mary’s court went to Mass three times a day, even in the Christmas season, and was terribly gloomy. They had one good Christmas, I think, when Philip first came over and she thought she was with child, but I was under house arrest then, I didn’t see what was done.”

“We shall have to make new traditions,” Cecil said, trying to cheer her.

“I don’t want new traditions,” she replied. “There has been too much change. People must see that things have been restored, that my court is as good as my father’s.”

Half a dozen household servants went past carrying a cartload of tapestries. One group turned in one direction, the others turned in the other, and the tapestries dropped between the six of them. They did not know where things were to go, the rooms had not been properly allocated. No one knew the rules of precedence in this new court; it was not yet established where the great lords would be housed. The traditional Catholic lords who had been in power under Queen Mary were staying away from the upstart princess; the Protestant arrivistes had not yet returned in their rush from foreign exile; the court officers, essential servants to run the great traveling business which was the royal court, were not yet commanded by an experienced Lord Chamberlain. It was all confused and new.

Robert Dudley stepped around the tumbled tapestries, strolled up and gave Elizabeth a smiling bow, doffing his scarlet cap with his usual flair. “Your Grace.”

“Sir Robert. You’re Master of Horse. Doesn’t that mean that you will take care of all the ceremonies and celebrations as well?”

“Of course,” he said easily. “I will bring you a list of entertainments that you might enjoy.”

She hesitated. “You have new ideas for entertainments?”

He shrugged, glancing at Cecil, as if he wondered what the question might mean. “I have some new ideas, Your Grace. You are a princess new-come to her throne, you might like some new celebrations. But the Christmas masque usually follows tradition. We usually have a Christmas banquet, and, if it is cold enough, an ice fair. I thought you might like a Russian masque, with bear baiting and savage dancing; and of course all the ambassadors will come to be presented, so we will need dinners and hunting parties and picnics to welcome them.”

Elizabeth was taken aback. “And you know how to do all this?”

He smiled, still not understanding. “Well, I know how to give the orders.”

Cecil had a sudden uncomfortable sense, very rare for him, of being out of his depth, faced with issues he did not understand. He felt poor, he felt provincial. He felt that he was his father’s son, a servant in the royal household, a profiteer from the sale of the monasteries, and a man who earned his fortune by marrying an heiress. The gulf between himself and Robert Dudley, always a great one, felt all at once wider. Robert Dudley’s grandfather had been a grandee at the court of Henry VII, his son the greatest man at the court of Henry VIII; he had been a kingmaker; he had even been, for six heady days, father-in-law to the Queen of England.

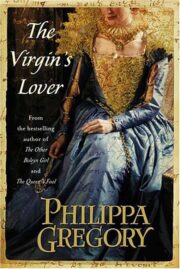

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.