“Spain will stand our friend,” Elizabeth reminded him.

“So can I send the Protestant lords some funds?” He pressed her with the main point, the only point.

“As long as no one knows it is from me,” Elizabeth said, her habitual caution uppermost as always. “Send them what they need, but I can’t have the French accuse me of arming a rebellion against a queen. I can’t be seen as a traitor.”

Cecil bowed. “It shall be done discreetly,” he promised her, hiding his immense sense of relief.

“And we may get help from Spain,” Elizabeth repeated.

“Only if they believe that you are seriously considering the Archduke Charles.”

“I am considering him,” she said emphatically. She handed the letter back into his hand. “And after this news, I am considering him with much affection. Trust me for that, Spirit. I am not joking. I know I will have to marry him if it comes to war.”

He doubted her word when she was in the royal box overlooking the tilt yard and he saw how her eyes searched the mounted riders for Dudley, how quickly she picked out his standard of the bear and ragged staff, how Dudley had a rose-pink scarf, the exact match of the queen’s gown, unquestionably hers, worn boldly on his shoulder where anyone could see. He saw that she was on her feet with her hand to her mouth in terror when Dudley charged down the list, how she applauded his victories, even when he unseated William Pickering, and how, when he came to the royal box and she leaned over and crowned him with her own circlet of roses for being the champion of the day, she all but kissed him on the mouth, she leaned so low and so smilingly whispered to him.

But despite all that, she had the Hapsburg ambassador, Caspar von Breuner, in the royal box beside her, fed him with delicacies of her own choosing, laid her hand on his sleeve, and smiled up into his face, and—whenever anyone but Dudley was jousting—plied him with questions about the Archduke Ferdinand and gave him very clearly to understand that her refusal of his proposal of marriage, earlier in the month, was one that she was beginning to regret, deeply regret.

Caspar von Breuner, charmed, baffled, and with his head quite turned, could only think that Elizabeth was seeing sense at last and the archduke could come to England to meet her and be married by the end of the summer.

The next night Cecil was alone when there was a tap on the door. His manservant opened the door. “A messenger.”

“I’ll see him,” Cecil said.

The man almost fell into the room, his legs weak with weariness. He put back his hood and Cecil recognized Sir Nicholas Throckmorton’s most trusted man. “Sir Nicholas sent me to tell you that the king is dead, and to give you this.” He proffered a crumpled letter.

“Sit down.” Cecil waved him to a stool by the fire and broke the seal on the letter. It was short and scrawled in haste. The king has died, this day, the tenth. God rest his soul. Young Francis says he is King of France and England. I hope to God you are ready and the queen resolute. This is a disaster for us all.

Amy, walking in the garden at Denchworth, picked some roses for their sweet smell and entered the house by the kitchen door to find some twine to tie them into a posy. As she heard her name she hesitated, and then realized that the cook, the kitchenmaid, and the spit boy were talking of Sir Robert.

“He was the queen’s own knight, wearing her favor,” the cook recounted with relish. “And she kissed him on the mouth before the whole court, before the whole of London.”

“God save us,” the kitchenmaid said piously. “But these great ladies can do as they please.”

“He has had her,” the spit lad opined. “Swived the queen herself! Now that’s a man!”

“Hush,” the cook said instantly. “No call for you to gossip about your betters.”

“My pa said so,” the boy defended himself. “The blacksmith told him. Said that the queen was nothing more than a whore with Robert Dudley. Dressed herself up as a serving wench to seek him out and that he had her in the hay store, and that Sir Robert’s groom caught them at it, and told the blacksmith himself, when he came down here last week to deliver my lady’s purse to her.”

“No!” said the kitchenmaid, deliciously scandalized. “Not on the hay!”

Slowly, holding her gown to one side so that it would not rustle, barely breathing, Amy stepped back from the kitchen door, walked back down the stone passageway, opened the outside door so that it did not creak, and went back out into the heat of the garden. The roses, unnoticed, fell from her fingers; she walked quickly down the path and then started to run, without direction, her cheeks burning with shame, as if it were she who was disgraced by the gossip. Running away from the house, out of the garden and into the shrubbery, through the little wood, the brambles tearing at her skirt, the stones shredding her silk shoes. Running, without pausing to catch her breath, ignoring the pain in her side and the bruising of her feet, running as if she could get away from the picture in her head: of Elizabeth like a bitch in heat, bent over in the hay, her red hair tumbled under a mobcap, her white face triumphant, with Robert, smiling his sexy smile, thrusting at her like a randy dog from behind.

The Privy Council, traveling on summer progress with the court, delayed the start of their emergency meeting at Eltham Palace for Elizabeth; but she was out hunting with Sir Robert and half a dozen others and no one knew when she would return. The councillors, looking grim, seated themselves at the table and prepared to do business with an empty chair at the head.

“If just one man will join with me, and the rest of you will give nothing more than your assent, I will have him murdered,” the Duke of Norfolk said quietly to this circle of friends. “This is intolerable. She is with him night and day.”

“You can do it with my blessing,” said Arundel, and two other men nodded.

“I thought she was mad for Pickering,” one man complained. “What’s become of him?”

“He couldn’t stand another moment of it,” Norfolk said. “No man could.”

“He couldn’t afford another moment of it,” someone corrected him. “He’s spent all his money on bribing friends at court and he’s gone to the country to recoup.”

“He knew he’d have no chance against Dudley,” Norfolk insisted. “That’s why he has to be got out of the way.”

“Hush, here is Cecil,” said another and the men parted.

“I have news from Scotland. The Protestant lords have entered Edinburgh,” Cecil said, coming into the room!

Sir Francis Knollys looked up. “Have they, by God! And the French regent?”

“She has withdrawn to Leith Castle. She is on the run.”

“Not necessarily so,” Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, said dourly. “The greater her danger, the more likely the French are to reinforce her. If it is to be finished, she must be defeated at once, without any hope of rallying, and it must be done quickly. She has raised a siege in the certain hope of reinforcements. All this means is that the French are coming to defend her. It is a certainty.”

“Who would finish it for us?” Cecil asked, knowing the most likely answer. “What commander would the Scots follow that would be our friend?”

One of the Privy Councillors looked up. “Where is the Earl of Arran?” he asked.

“On his way to England,” Cecil replied, hiding his sense of smugness. “When he gets here, if we can come to an agreement with him, we could send him north with an army. But he is only young…”

“He is only young, but he has the best claim to the throne after the French queen,” someone said farther down the table. “We can back him with a clear conscience. He is our legitimate claimant to the throne.”

“There is only one agreement that he would accept and that we could offer,” Norfolk said dourly. “The queen.”

A few men glanced at the closed door as if to ensure that it did not burst open and Elizabeth storm in, flushed with temper. Then, one by one, they all nodded.

“What of the Spanish alliance with the archduke?” Francis Bacon, brother to Sir Nicholas, asked Cecil.

Cecil shrugged. “They are still willing and she says she is willing to have him. But I’d rather we had Arran. He is of our faith, and he brings us Scotland and the chance to unite England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. That would make us a power to reckon with. The archduke keeps the Spanish on our side, but what will they want of us? Whereas Arran’s interests are the same as ours, and if they were to marry,” he took a breath, his hopes were so precious he could hardly bear to say them, “if they were to marry we would unite Scotland and England.”

“Yes: if,” Norfolk said irritably. “If we could make her seriously look twice at any man who wasn’t a damned adulterous rascal.”

Most of the men nodded.

“Certainly we need either Spanish help or Arran to lead the campaign,” Knollys said. “We cannot do it on our own. The French have four times our wealth and manpower.”

“And they are determined,” another man said uneasily. “I heard from my cousin in Paris. He said that the Guise family will rule every thing, and they are sworn enemies of England. Look at what they did in Calais; they just marched in. They will take one step in Scotland and then they will march on us.”

“If she married Arran…” someone started.

“Arran! What chance of her marrying Arran!” Norfolk burst out. “All very well to consider which suitor would be the best for the country, but how is she to marry while she sees no one and thinks of no one but Dudley? He has to be put out of the way. She is like a milkmaid with a swain. Where the devil is she now?”

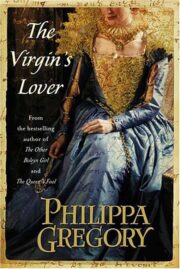

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.