“With her women in attendance,” Robert stated.

The spy shook his head. “Completely alone, sir. Just the two of them. Five hours behind a closed door, before they came out.”

Robert was staggered at a privilege that he had never had. “Cecil allowed this?” he demanded incredulously.

Thomas Blount shrugged. “I don’t know, sir. He must have done, for the next day she saw Sir William again.”

“Alone?”

“All the afternoon. From noon till dinner time. They are taking bets on him being her husband. He’s the favorite; he’s overtaken the archduke. They are saying that they’ve wedded and bedded in private, all that is lacking is an announcement.”

Robert exclaimed and whirled away, and then turned back. “And what does he do now? Is he to stay at court?”

“He is the favorite. She has given him a suite of rooms near to hers in Greenwich Palace.”

“How near?”

“They say there is a passageway that he can go to her at any time of the night or day. She has only to unlock the door and he can walk into her bedchamber.”

Robert suddenly became very still and calm. He glanced at his horse as the groom walked it up and down the yard, noting the sweat on its neck and the foam at its mouth, as if he were contemplating starting his journey at once.

“No,” he said softly to himself. “Better tomorrow, rested with a clear head. With a rested horse. Any other news?”

“That the Protestants are rioting against the French regent in Scotland, and she is massing her soldiers, calling for more men from France.”

“I knew that before I left court,” Robert said. “Does Cecil work on the queen to send support?”

“Still,” the man said. “But she says nothing either one way or the other.”

“Too busy with Pickering, I suppose,” Robert said sourly, and turned to go into the house. “You can wait here and ride back with me tomorrow,” he said shortly. “I obviously cannot risk being away for even a moment. We leave for Greenwich at first light. Tell my people that we leave at dawn and that we will ride hard.”

Amy, sick with tears, was waiting, as humble as any petitioner, outside the door of Robert’s privy chamber. She had seen him ride in on his lathered horse, and had hovered on the stairs hoping to speak to him. He had gone past her with a brief, courteous word of apology. He had washed and changed his clothes; she had heard the clink of jug against bowl. Then he had gone into his privy chamber, closed the door, and was clearly packing his books and his papers. Amy guessed that he was leaving, and she did not dare to knock on his door and beg him to stay.

Instead she waited outside, perched on the plain wooden window seat, like an apologetic child waiting to see an angry father.

When he opened the door she leapt to her feet and he saw her in the shadows. For a moment he had quite forgotten the quarrel, then his dark, thick eyebrows snapped together in a scowl. “Amy.”

“My lord!” she said; the tears flooded into her eyes and she could not speak. She could only stand dumbly before him.

“Oh, for God’s sake,” he said impatiently and kicked open the door of his room with his booted foot. “You had better come in before the whole world thinks that I beat you.”

She went before him into his room. As she had feared, it was stripped of all the papers and books that he had brought. Clearly, he was packed and ready to leave.

“You’re not going?” she said, her voice tremulous.

“I have to,” he said. “I had a message from court; there is some business which demands my attention, at once.”

“You are going because you are angry with me,” she whispered.

“No, I am going because I had a message from court. Ask William Hyde, he saw the messenger and told him to wait for me.”

“But you are angry with me,” she persisted.

“I was,” he said honestly. “But now I am sorry for my temper. I am not leaving because of the house, nor what I said. There are things at court that I have to attend to.”

“My lord…”

“You shall stay here for another month, perhaps two, and when I write to you, you can move to the Hayes’ at Chislehurst. I will come and see you there.”

“Am I not to find us a house here?”

“No,” he said shortly. “Clearly, we have very different ideas as to what a house should be like. We will have to have a long conversation about how you wish to live and what I need. But I cannot discuss this now. Right now I have to go to the stables. I will see you at dinner. I shall leave at dawn tomorrow; there is no need for you to rise to see me off. I am in a hurry.”

“I should not have said what I said. I am most sorry, Robert.”

His face tightened. “It is forgotten.”

“I can’t forget it,” she said earnestly, pressing him with her contrition. “I am sorry, Robert. I should not have mentioned your disgrace and your father’s shame.”

He took a breath, trying to hold back his sense of outrage. “It would be better if we forgot that quarrel, and did not repeat it,” he cautioned her, but she would not be cautioned.

“Please, Robert, I should not have said what I did about you chasing after grandeur and not knowing your place—”

“Amy, I do remember what you said!” he broke in. “There is no need for you to remind me. There is no need to repeat the insult. I do remember every word and that you spoke loud enough for William Hyde, his wife, and your companion to hear it too. I don’t doubt that they all heard you abuse me, and my father. I don’t forget you named him as a failed traitor and blamed me for the loss of Calais. You blamed him for the death of my brother Guilford and me for the death of my brother Henry. If you were one of my servants I would have you whipped and turned away for saying half of that. I’d have your tongue slit for scandal. You would do better not to remind me, Amy. I have spent most of this day trying to forget your opinion of me. I have been trying to forget that I live with a wife who despises me as an unsuccessful traitor.”

“It’s not my opinion,” she gasped. She was on the floor kneeling at his feet in one smooth movement, hammered down by his anger. “I do not despise you. It is not my opinion; I love you, Robert, and I trust you—”

“You taunted me with the death of my brother,” he said coldly. “Amy, I do not want to quarrel with you. Indeed, I will not. You must excuse me now; I have to see about something in the stables before I go to dinner.”

He swept her a shallow bow and went from the room. Amy scrambled up from her subservient crouch on the floor and ran to the door. She would have torn it open and gone after him but when she heard the brisk stride of his boots on the wooden floor she did not dare. Instead she pressed her hot forehead to the cool paneling of the door and wrapped her hands around the handle, where his hand had been.

Dinner was a meal where good manners overlaid discomfort. Amy sat in stunned silence, eating nothing; William Hyde and Robert maintained a pleasant flow of conversation about horses and hunting and the prospect of war with the French. Alice Hyde kept her head down, and Lizzie watched Amy as if she feared she would faint at the table. The ladies withdrew as soon as they could after dinner and Robert, pleading an early start, left soon after. William Hyde took himself into his privy chamber, poured himself a generous tumbler of wine, turned his big wooden chair to the fire, put his feet up on the chimney breast, and fell to considering the day.

His wife, Alice, put her head round the door and came quietly into the room, followed by her sister-in-law. “Has he gone?” she asked, determined not to meet with Sir Robert again, if she could avoid him.

“Aye. You can take a chair, Alice, Sister, and pour yourselves your wine if you please.”

They served themselves and drew up their chairs beside his, in a conspiratorial semicircle around the fire.

“Is that the end of his plans to build here?” William asked Lizzie Oddingsell.

“I don’t know,” she said quietly. “All she told me was that he is very angry with her, and that we’re to stay here another month.”

A quick glance between William and Alice showed that this had been a matter of some discussion. “I think he won’t build,” he said. “I think all she showed him today was how far apart they have become. Poor, silly woman. I think she has dug her own grave.”

Lizzie quickly crossed herself. “God’s sake, brother! What do you mean? They had a quarrel. You show me a man and wife who have not had cross words.”

“This is not an ordinary man,” he said emphatically. “You heard him, just as she heard him, but neither of you have the wit to learn. He told her to her face: he is the greatest man in the kingdom. He stands to be the wealthiest man in the kingdom. He has the full attention of the queen; she is always in his company. He is indispensable to the first spinster queen this country has ever known. What d’you think that might mean? Think it out for yourself.”

“It means he will want a country estate,” Lizzie Oddingsell pursued. “As he rises at court. He will want a great estate for his wife and for his children, when they come, please God.”

“Not for this wife,” Alice said shrewdly. “What has she ever done but be a burden to him? She does not want what he wants: not the house, not the life. She accuses him of ambition when that is his very nature, his blood and his bone.”

Lizzie would have argued to defend Amy, but William hawked and spat into the fire. “It does not matter if she pleases him or fails him,” he said flatly. “He has other plans now.”

“Do you think he means to put her aside?” Alice asked her husband.

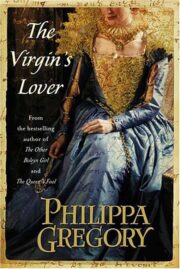

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.