“Just as I predicted,” William Hyde muttered quietly and pulled his horse gently away from the group, nodding to his wife for her to come with him, out of earshot.

“Why, yes,” Amy said, still smiling confidently. “I know the house is not big enough, but that barn could become another wing, it is high enough to build a floor in the eaves, just as they did at Hever, and then you have bedrooms above and a hall below.”

“And what plans did you have for the midden?” he demanded. “And the duck pond?”

“We would clear the midden, of course,” she said, laughing at him. “That would never do! It would be the first thing, of course. But we could spread it on the garden and plant some flowers.”

“And the duck pond? Is that to become an ornamental lake?”

At last she heard the biting sarcasm in his tone. She turned in genuine surprise. “Don’t you like it?”

He closed his eyes and saw at once the doll’s-house prettiness of the Dairy House at Kew, and the breakfast served by shepherdesses in the orchard with the tame lambs dyed green and white, skipping around the table. He thought of the great houses of his boyhood, of the serene majesty of Syon House, of Hampton Court, one of his favorite homes and one of the great palaces of Europe, of the Nonsuch at Sheen, or the Palace at Greenwich, of the walled solidity of Windsor, of Dudley Castle, his family seat. Then he opened his eyes and saw, once again, this place that his wife had chosen: a house built of mud on a plain of mud.

“Of course I don’t like it. It is a hovel,” he said flatly. “My father used to keep his sows in better sties than this.”

For once, she did not crumple beneath his disapproval. He had touched her pride, her judgment in land and property.

“It is not a hovel,” she replied. “I have been all over it. It is soundly built from brick and lathe and plaster. The thatch is only twenty years old. It needs more windows, for sure, but they are easily made. We would rebuild the barn, we would enclose a pleasure garden, the orchard could be lovely, the pond could be a boating lake, and the land is very good, two hundred acres of prime land. I thought it was just what we wanted, and we could make anything we want here.”

“Two hundred acres?” he demanded. “Where are the deer to run? Where is the court to ride?”

She blinked.

“And where will the queen stay?” he demanded acerbically. “In the henhouse, out the back? And the court? Shall we knock up some hovels on the other side of the orchard? Where will the royal cooks prepare her dinner? On that open fire? And where will we stable her horses? Shall they come into the house with us, as clearly they do at present? We can expect about three hundred guests; where do you think they will sleep?”

“Why should the queen come here?” Amy asked, her mouth trembling. “Surely she will stay at Oxford. Why should she want to come here? Why would we ask her here?”

“Because I am one of the greatest men at her court!” he exclaimed, slamming his fist down on the saddle and making his horse jump and then sidle nervously. He held it on a hard rein, pulling on its mouth. “The queen herself will come and stay at my house to honor me! To honor you, Amy! I asked you to find us a house to buy. I wanted a place like Hatfield, like Theobalds, like Kenninghall. Cecil goes home to Theobalds Palace, a place as large as a village under one roof; he has a wife who rules it like a queen herself. He is building Burghley to show his wealth and his grandeur; he is shipping in stonemasons from all over Christendom. I am a better man than Cecil, God knows. I come from stock that makes him look like a sheepshearer. I want a house to match his, stone for stone! I want the outward show that matches my achievements.

“For God’s sake, Amy, you’ve stayed with my sister at Penshurst! You know what I expect! I didn’t want some dirty farmhouse that we could clean up so that at its best, it was fit for a peasant to breed dogs in!”

She was trembling, hard put to keep her grip on the reins. From a distance, Lizzie Oddingsell watched and wondered if she should intervene.

Amy found her voice. She raised her drooping head. “Well, all very well, husband, but what you don’t know is that this farm has a yield of—”

“Damn the yield!” he shouted at her. His horse shied and he jabbed at it with a hard hand. It jibbed and pulled back, frightening Amy’s horse who stepped back, nearly unseating her. “I care nothing for the yield! My tenants can worry about the yield. Amy, I am going to be the richest man in England; the queen will pour the treasury of England upon me. I don’t care how many haystacks we can make from a field. I ask you to be my wife, to be my hostess at a house which is of a scale and of a grandeur—”

“Grandeur!” she flared up at him. “Are you still running after grandeur? Will you never learn your lesson? There was nothing very grand about you when you came out of the Tower, homeless and hungry; there was nothing very grand about your brother when he died of jail fever like a common criminal. When will you learn that your place is at home, where we might be happy? Why will you insist on running after disaster? You and your father lost the battle for Jane Grey, and it cost him his son and his own life. You lost Calais and came home without your brother and disgraced again! How low do you need to go before you learn your lesson? How base do you have to sink before you Dudleys learn your limits?”

He wheeled his horse and dug his spurs into its sides, wrenching it back with the reins. The horse stood up on its hind legs in a high rear, pawing the air. Robert sat in the saddle like a statue, reining back his rage and his horse with one hard hand. Amy’s horse shield away, frightened by the flailing hooves, and she had to cling to the saddle not to fall.

His horse dropped down. “Fling it in my face every day if you please,” he hissed at her, leaning forward, his voice filled with hatred. “But I am no longer Sir John Robsart’s stupid young son-in-law, out of the Tower and still attainted. I am Sir Robert Dudley once more; I wear the Order of the Garter, the highest order of chivalry there is. I am the queen’s Master of Horse, and if you cannot take a pride in being Lady Dudley then you can go back to being Amy Robsart, Sir John Robsart’s stupid daughter, once more. But for me: those days are gone.”

Fearful of falling from her frightened horse, Amy kicked her feet free and jumped from the saddle. On the safety of the ground she turned and glared up at him as he towered over her, his big horse curvetting to be away. Her temper rose up, flared into her cheeks, burned in her mouth.

“Don’t you dare to insult my father,” she swore at him. “Don’t you dare! He was a better man than you will ever be, and he won his lands by honest work and not by dancing at some heretic bastard’s bidding. And don’t say yields don’t matter! Who are you to say that yields don’t matter? You would have starved if my father had not kept his land in good heart, to put food on your plate when you had no way of earning it. You were glad enough of the wool crop then! And don’t call me stupid. The only stupid thing I ever did was to believe you and your braggart father when you came riding into Stanfield Hall, and not long after, you were riding into the Tower on a cart as traitors.” She was almost gibbering in her rage. “And don’t you dare threaten me. I shall be Lady Dudley to the day of my death! I have been through the worst with you when my name was a shame to me. But now neither you nor your heretic pretender can take it away from me.”

“She can take it away,” he said bitingly. “Fool that you are. She can take it away tomorrow, if she wants it. She’s supreme governor of the church of England. She can take away your marriage if she wants it and better women than you have been divorced for less than this… this… shite-house pipe dream.”

His big horse reared, Amy ducked away, and Sir Robert let the horse go, tearing up the earth with its big hooves, thundering away along the lane, leaving them in a sudden silence.

When they got home there was a man in the stable yard waiting for Robert Dudley. “Urgent message,” he said to William Hyde. “Can you send a groom to guide me to where I might find him?”

William Hyde’s square face creased with concern. “I don’t know where he might be,” he said. “He went for a ride. Will you come into the house and take a cup of ale while you’re waiting?”

“I’ll follow him,” the man said. “His lordship likes his messages delivered at once.”

“I don’t know which direction he took,” William said tactfully. “You’d better come inside to wait.”

The man shook his head. “I’d be obliged to you for a drink out here, but I’ll wait here for him.”

He sat on the mounting block and did not shift until the sun dropped lower in the sky, until finally he heard the clip-clop of hooves and Robert rode up the lane and into the stable yard and tossed the reins of his weary horse to a waiting groom.

“Blount?”

“Sir Robert.”

Robert drew him to one side, his rage with Amy all forgotten. “Must be important?”

“Sir William Pickering is back in England.”

“Pickering? The queen’s old flirt?”

“He was not sure if he would be welcomed, not sure how long her memory would be. There were rumors that he had served her sister. He did not know what she might have heard.”

“She would have heard everything,” Dudley said dourly. “You can trust to me and Cecil for that. Anyway, did she welcome him?”

“She saw him alone.”

“What? A private audience? She saw him in private? Dear God, he’s honored.”

“No, I mean alone. Completely alone. For all the afternoon, five hours he was locked up with her.”

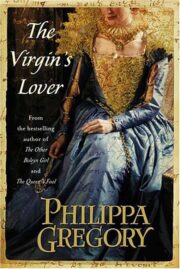

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.