“Ah yes, you are a Spaniard now,” Elizabeth said, as if it were a disease that Jane had caught.

“A Spanish countess,” Jane replied smoothly. “Yes, we have both changed our places in the world since we last met, Your Grace.”

It was a shrewd reminder. Jane had seen Elizabeth on her knees and weeping with pretended penitence before her sister, had seen Elizabeth bloated with illness, under house arrest, under charge of treason, sick with terror, begging for a hearing.

“Well, I wish you a good journey anyway,” Elizabeth said carelessly.

Jane sank to the ground in a perfect courtly curtsy; no one could have known that she was on the very edge of losing consciousness. She rose up and saw the room swim before her eyes, and then she walked backward from the throne, one smooth step after another, her rich gown held out of the way of her scarlet high heels, her head up, her lips smiling. She did not turn until she reached the door. Then she flicked her skirt around and left, without a backward glance.

“She did what?” Cecil demanded incredulously of an excitable Laetitia Knollys, reporting, as she was paid to do, on the doings of the queen’s private rooms.

“Kept her waiting for a full half hour, and then suggested that she had the baby in her belly before marriage,” Laetitia whispered breathlessly.

They were in Cecil’s dark paneled study, the shutters closed although it was full day, a trusted man on the door and Cecil’s other rooms barred to visitors.

He frowned slightly. “And Jane Dormer?”

“She was like a queen,” Laetitia said. “She spoke graciously, she curtsyed—you should have seen her curtsy—she went out as if she despised us all, but gave said not one word of protest. She made Elizabeth look like a fool.”

Cecil frowned slightly. “Watch your speech, little madam,” he said firmly. “I would have been whipped if I had called my king a fool.”

Laetitia bowed her bronze head.

“Did Elizabeth say anything when she had gone?”

“She said that Jane reminded her of her sour-faced old sister and thank God those days were past.”

He nodded. “Anyone reply?”

“No!” Laetitia was bubbling with gossip. “Everyone was so shocked that Elizabeth should be so …so…” She had no words for it.

“So what?”

“So nasty! So rude! She was so unkind! And to such a nice woman! And her with child! And the wife of the Spanish ambassador! Such an insult to Spain!”

Cecil nodded. It was a surprising indiscretion for such a controlled young woman, he thought. Probably the relic of some foolish women’s quarrel that had rumbled on for years. But it was unlike Elizabeth to show her hand with quite such vulgarity. “I think you will find that she can be very nasty,” was all he said to the girl. “You had better make sure you never give her cause.”

Her head came up at that, her dark eyes, Boleyn eyes, looked at him frankly. She smoothed her bronze hair under her cap. She smiled, that bewitching, sexually aware Boleyn smile. “How can I help it?” she asked him limpidly. “She only has to look at me to hate me.”

Later that night Cecil called for fresh candles and another log for the fire. He was writing to Sir James Croft, an old fellow-plotter. Sir James was at Berwick but Cecil had decided that the time had come for him to visit Perth.

Scotland is a tinderbox, he wrote in the code that he and Sir James had used to each other since Mary Tudor’s spy service had intercepted their letters, and John Knox is the spark that will set it alight. My commission for you is to go to Perth and do nothing more than observe. You should get there before the forces of the queen regent arrive. My guess is that you will see John Knox preaching the freedom of Scotland to an enthusiastic crowd. I should like to know how enthusiastic and how effective. You will have to make haste because the queen regent’s men may arrest him. He and the Scottish Protestant lords have asked for our help but I would know what sort of men they are before I commit the queen. Talk to them, take their measure. If they would celebrate their victory by turning the country against the French, and in alliance with us, they can be encouraged. And let me know at once. Information is a better coin than gold here.

Summer 1559

ROBERT FINALLY ARRIVED at Denchworth in the early days of June, all smiles and apologies for his absence. He told Amy that he could be excused from court for a few days since the queen, having formally refused the Archduke Ferdinand, was now inseparable from his ambassador, talking all the time about his master, and showing every sign of wishing to change her mind and marry him.

“She is driving Cecil mad,” he said, smiling. “No one knows what she intends or wants at all. She has refused him but now she talks about him all the time. She has no time for hunting, and no interest for riding. All she wants to do is to walk with the ambassador or practice her Spanish.”

Amy, with no interest in the flirtations of the queen or of her court, merely nodded at the news and tried to turn Robert’s attention to the property that she had found. She ordered horses from the stables for Robert, the Hydes, Lizzie Oddingsell, and for herself, and led the way on the pretty cross-country drover’s track to the house.

William Hyde found his way to Robert’s side. “What news of the realm?” he asked. “I hear that the bishops won’t support her.”

“They say they won’t take the oath confirming her as supreme governor,” Robert said briefly. “It is treason, as I tell her. But she is merciful.”

“What will she …er…mercifully do?” Mr. Hyde asked nervously, the burning days of Mary Tudor still very fresh in his memory.

“She’ll imprison them,” Robert said bluntly. “And replace them with Protestant clergy if she cannot find any Catholics to see reason. They have missed their chance. If they had called in the French before she was crowned they might have turned the country against her, but they have left it too late.” He grinned. “Cecil’s advice,” he said. “He had their measure. One after another of them will cave in or be replaced. They did not have the courage to rise against her with arms; they only stand against her on theological grounds, and Cecil will pick them off.”

“But she will destroy the church,” William Hyde said, shocked.

“She will break it down and make it new,” Dudley, the Protestant, said with pleasure. “She has been forced into a place where it is either the Catholic bishops or her own authority. She will have to destroy them.”

“Does she have the strength?”

Dudley raised a dark eyebrow. “It does not take much strength to imprison a bishop, as it turns out. She has half of them under house arrest already.”

“I mean strength of mind,” William Hyde said. “She is only a woman, even though a queen. Does she have the courage to go against them?”

Dudley hesitated. It was always everyone’s fear, since everyone knew that a woman could neither think nor do anything with any consistency. “She is well advised,” he said. “And her advisors are good men. We know what has to be done, and we keep her to it.”

Amy reined back her horse and joined them.

“Did you tell Her Grace that you were coming to look at a house?” she asked.

“Indeed yes,” he said cheerfully as they crested one of the rolling hills. “It’s been too long since the Dudleys had a family seat. I tried to buy Dudley Castle from my cousin, but he cannot bear to let it go. Ambrose, my brother, is looking for somewhere too. But perhaps he and his family could have a wing of this place. Is it big enough?”

“There are buildings that could be extended,” she said. “I don’t see why not.”

“And was it a monastic house, or an abbey or something?” he asked. “A good-sized place? You’ve told me nothing about it. I have been imagining a castle with a dozen pinnacles!”

“It’s not a castle,” she said, smiling. “But I think it is a very good size for us. The land is in good heart. They have farmed it in the old way, in strips, changing every Michaelmas, so it has not been exhausted. And the higher fields yield good grass for sheep, and there is a very pretty wood that I thought we might thin and cut some rides through. The water meadows are some of the richest I have ever seen, the milk from the cows must be almost solid cream. The house itself is a little too small, of course, but if we added a wing we could house any guests that we had…”

She broke off as their party rounded the corner in the narrow lane and Robert saw the farmhouse before him. It was long and low, an animal barn at the west end built of worn red brick and thatched in straw like the house, only a thin wall separating the beasts from the inhabitants. A small tumbling-down stone wall divided the house from the lane and inside it, a flock of hens scratched at what had once been a herb garden but was now mostly weeds and dust. To the side of the ramshackle building, behind the steaming midden, was a thickly planted orchard, boughs leaning down to the ground and a few pigs rooting around. Ducks paddled in the weedy pond beyond the orchard; swallows swooped from pond to barn, building their nests with beakfuls of mud.

The front door stood open, propped with a lump of rock. Robert could glimpse a low, stained ceiling and an uneven floor of stone slabs scattered with stale herbs but the rest of the interior was hidden in the gloom since there were almost no windows, and choked with smoke since there was no chimney but only a hole in the roof.

He turned to Amy and stared at her as if she were a fool, brought to beg for his mercy. “You thought that I would want to live here?” he asked incredulously.

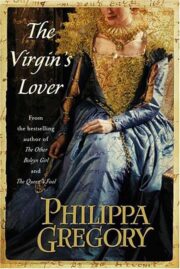

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.