Mr. Hyde’s house was a handsome place, set back a little from the village green, with a good sweep of a drive up to it and high walls built in the local stone. It had once been a farmhouse and successive additions had given it a charming higgledy-piggledy roof line, and extra wings branching from the old medieval hall. Amy had always enjoyed staying with the Hydes; Mrs. Oddingsell was sister to Mr. Hyde and there was always a warm sense of a family visit which hid the awkwardness that Amy sometimes felt when she arrived at one of Robert Dudley’s dependents. Sometimes it seemed as if she were Robert’s burden which had to be shared equally among his adherents; but with the Hydes she was among friends. The rambling farmhouse set in the wide open fields reminded her of her girlhood home in Norfolk, and the small worries of Mr. Hyde, the dampness of the hay, the yield of the barley crop, the failure of the river to flood the water meadows since a neighbor had put in an overly deep carp pond, were the trivial but fascinating business of running a country estate that Amy knew and loved.

The children were on the watch for their Aunt Lizzie and Lady Dudley; when the little cavalcade came up the drive the front door opened and they came tumbling out, waving and dancing around.

Lizzie Oddingsell tumbled off her horse and hugged them indiscriminately, and then straightened up to kiss her sister-in-law, Alice, and her brother, William.

They all three turned and hurried to help Amy down from her horse.

“My dear Lady Dudley, you are most welcome to Denchworth,” William Hyde said warmly. “And are we to expect Sir Robert?”

Her blaze of a smile warmed them all. “Oh, yes,” she said. “Within a fortnight, and I am to look for a house for us and we are going to have an estate here!”

Robert, walking around the Whitehall Palace stable yard on one of his weekly inspections, turned his head to hear a horse trotting rapidly on the cobbled road and then saw Thomas Blount jump from his hard-ridden mare, throw the reins at a stable lad, and march toward the pump as if urgently needing to sluice his head with water. Obligingly, Robert worked the pump handle.

“News from Westminster,” Thomas said quickly. “And I think I am ahead of anyone else. Perhaps of interest to you.”

“Always of interest. Information is the only true currency.”

“I have just come from parliament. Cecil has done it. They are going to pass the bill to change the church.”

“He’s done it?”

“Two bishops imprisoned, two said to be ill, and one missing. Even so, he did it by only three votes. I came away as soon as I had counted the heads and I am sure of it.”

“A new church,” Dudley said thoughtfully.

“And a new head of the church. She’s to be supreme governor.”

“Supreme governor?” Dudley demanded, querying the curious name. “Not head?”

“That’s what they said.”

“That’s an odd thing,” Dudley said, more to himself than to Blount.

“Sir?”

“Makes you think.”

“Does it?”

“Makes you wonder what she might do.”

“Sir?”

“Nothing, Blount.” Dudley nodded to the man. “My thanks.” He walked on, shouted for a stable lad to move a halter rope, finished his inspection in a state of quiet elation, then turned and went slowly up the steps toward the palace.

On the threshold he met William Cecil, dressed for the journey to his home at Theobalds.

“Oh, Lord Secretary, good day. I was just thinking about you.” Dudley greeted him jovially and patted him on the shoulder.

Cecil bowed. “I am honored to occupy your thoughts,” he said with the ironic courtesy that he often used to keep Dudley at a safe distance, and to remind them both that the old relationship of master and servant no longer applied.

“I hear you have triumphed and remade the church?” Dudley inquired.

How the devil does he know that? Cecil demanded of himself. And why can’t he just dance with her and ride with her and keep her happy till I can get her safely married to the Earl of Arran?

“Yes, a pity in many ways. But at last we have agreement,” Cecil said, gently detaching his sleeve from the younger man’s detaining hand.

“She is to be governor of the church?”

“No more and no less than her father, or her brother.”

“Surely they were called head of the church?”

“St. Paul was thought to have ruled against a woman’s ministry,” Cecil volunteered. “So she could not be called head. Governor was deemed to be acceptable. But if you are troubled in your conscience, Sir Robert, there are spiritual leaders who can guide you better than I.”

Robert gave a quick laugh at Cecil’s wonderful sarcasm. “Thank you, my lord. But my soul can generally be trusted to look after itself in these matters. Will the clergy thank you for such a thing?”

“They will not thank us,” Cecil said carefully. “But they may be coerced and slid and argued and threatened into agreement. I expect a struggle. It will not be easy.”

“And how will you coerce and slide them and argue with them and threaten them?”

Cecil raised an eyebrow. “By administering an oath, the Oath of Supremacy. It’s been done before.”

“Not to a church that was wholly opposed,” Dudley suggested.

“We have to hope that they will not be wholly opposed when it comes to a choice between swearing an oath or losing their livelihood and their freedom,” Cecil said pleasantly.

“You don’t propose to burn?” Dudley asked baldly.

“I trust it will not come to that, though her father would have done so.”

Robert nodded. “Does all the power come to her, despite the different name? Does it give her all the powers of her father? Of her brother? Is she to be Pope in England?”

Cecil gave a little dignified bow, preparatory to making his leave. “Yes indeed, and if you will excuse me…”

To his surprise the younger man no longer detained him but swept him a graceful bow and came up smiling. “Of course! I should not have delayed you, Lord Secretary. Forgive me. Are you on your way home?”

“Yes,” Cecil said. “Just for a couple of days. I shall be back in plenty of time for your investiture. I must congratulate you on the honor.”

So how does he know about that? Dudley demanded of himself. She swore to me that she would tell no one till nearer the time. Did he get it by his spies, or did she tell him herself? Does she indeed tell him everything? Aloud he said, “I thank you. I am too much honored.”

You are indeed, Cecil said to himself, returning the bow and making his way down the steps to where his short-backed horse was waiting for him, and his entourage was assembling. But why should you be so delighted that she is head of the church? What is it to you, you sly, unreliable, handsome coxcomb?

She is to be the English Pope, Robert whispered to himself, strolling like a prince at leisure in the opposite direction. The soldiers at the end of the gallery threw open the double doors for him and Robert passed through. The intense charm of his smile made them duck their heads and shuffle their feet, but his smile was not for them. He was smiling at the exquisite irony of Cecil serving Robert, all unknowing. Cecil, the great fox, had fetched home a game bird, and laid it at Robert’s feet, as obedient as a Dudley spaniel.

He has made her Pope in everything but name. She can grant a dispensation for a marriage, she can grant an annulment of a marriage, she can rule in favor of a divorce, Robert whispered to himself. He has no idea what he has done for me. By persuading those dull squires to make her supreme governor of the Church of England he has given her the power to grant a divorce. And who do we know who might benefit from that?

Elizabeth was not thinking of her handsome Master of Horse. Elizabeth was in her presence chamber, admiring a portrait of Archduke Ferdinand, her ladies around her. From the ripple of approval as they noted the Hapsburg darkness of his eyes and the high fashion of his clothes Robert, entering the room at a leisurely stroll, understood that Elizabeth was continuing her public courtship of this latest suitor.

“A handsome man,” he said, earning a smile from her. “And a good stance.”

She took a step toward him, Robert, alert as a choreographer to every move of a dance, stood stock still and let her come to him.

“You admire the archduke, Sir Robert?”

“Certainly, I admire the portrait.”

“It is a very good likeness,” the ambassador Count von Helfenstein said defensively. “The archduke has no vanity, he would not want a portrait to flatter or deceive.”

Robert shrugged, smiling. “Of course not,” he said. He turned to Elizabeth. “But how could one choose a man from canvas and paint? You would never choose a horse like that.”

“Yes; but an archduke is not a horse.”

“Well, I would want to know how my horse would move, before I gave myself up to desire for him,” he said. “I would want to put him through his paces. I would want to know how he felt when I gentled him under my hand, smoothed his neck, touched him everywhere, behind the ears, on the lips, behind the legs. I would want to know how responsive he was when I was on him, when I had him between my legs. You know, I would even want to know the smell of him, the very scent of his sweat.”

She gave a little gasp at the picture he was drawing for her, so much more vivid, so much more intimate, than the dull oil on canvas before them.

“If I were you, I would choose a husband I knew,” he said quietly to her. “A man I had tested with my own eyes, with my own fingers, whose scent I liked. I would only marry a man I knew I could desire. A man I already desired.”

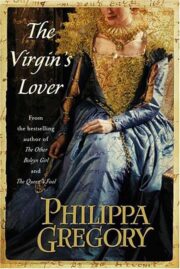

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.