“Lady Jane was not the true heir,” Cecil pointed out to Lady Jane’s brother-in-law, not mincing his words. “And the crown was crammed on her head by a traitor, also beheaded for treason. Your father, actually.”

Dudley’s gaze did not waver. “He paid the price for that treason,” he said simply. “And I paid for my part in it. I paid in full. There’s not a man in her court that has not had to loosen his collar and turn his coat once or twice in recent years. Even you, sir, I imagine, though you kept yourself clear of our disgrace.”

Cecil, whose hands were cleaner than most, let it go. “Perhaps. But there is one thing I should tell you.”

Dudley waited. Cecil leaned toward him and kept his voice low. “There is no money for this,” he said heavily. “The treasury is all but empty. Queen Mary and her Spanish husband have drained England dry. We cannot pay for tableaux and fountains running with wine, and cloth of gold to drape around arches. There is no gold in the treasury; there is barely enough plate for a banquet.”

“It’s as bad as that?”

Cecil nodded. “Worse.”

“Then we will have to borrow it,” Robert declared grandly. “For I will have her crowned in state. Not for my vanity, which I know is not of the smallest, not for hers, and you will find she is no shy violet either; but because this puts her more firmly on the throne than a standing army. You will see. She will make them hers. But she has to come out from the Tower on a great white horse and with her hair spread over her shoulders and she has to look every inch a queen.”

Cecil would have argued but Robert went on. “She has to have people crying out for her; she has to have tableaux declaring her as the true and only heir: pictures for the people who cannot read your proclamations, who have no knowledge of the law. She has to be surrounded by a beautiful court and a cheering, prosperous crowd. This is how we make her a queen indeed: now, and for the rest of her life.”

Cecil was struck by the vividness of the younger man’s vision. “You really believe it makes her safer?”

“She can make herself safe,” Robert said earnestly. “Give her a stage and she will be the only sight anyone can see. This coronation gives her a platform that will put her head and shoulders above anyone else in England, her cousins, rival heirs, anyone. This gives her men’s hearts and souls. You have to get the money so that I can build her the stage, and she will do the rest. She will enact the part of queen.”

Cecil took a turn to the window and looked out over the wintry gardens of Whitehall Palace. Robert drew closer, scanning the older man’s profile. Cecil was nearing forty, a family man, a quiet Protestant through the Catholic years of Mary Tudor, a man with an affection for his wife and for accruing land. He had served the young Protestant king, he had refused to be a part of the Jane Grey plot, and then he had been steadily and discreetly loyal to Princess Elizabeth, taking the inferior job of surveyor so that he might keep her small estates in good heart, and have an excuse for seeing her often. It was Cecil’s advice that had kept her out of trouble during the years of plotting and the uprisings against her sister Mary. It would be Cecil’s advice that would keep her steady on this new throne. Robert Dudley might not like him, in truth, he would never like any rival; but he knew that this man would be making the decisions for the young queen.

“And so?” he said finally.

Cecil nodded. “We’ll raise the money from somewhere,” he said. “We’ll have to borrow. But for God’s sake, for her sake, keep it as cheap as possible.”

Robert Dudley shook his head in instinctive rejection. “This cannot be cheap!” he declared.

“It cannot look cheap,” Cecil corrected him. “But it can be affordable. Do you know her fortune?”

He knew that Robert did not know. Nobody had known, until the clerk of the Privy Council Armagil Waad, had emerged from the royal treasury, which he had last seen filled with gold, with the most rudimentary of inventories shaking in his hand, and whispered, aghast: “Nothing. There is nothing left. Queen Mary has spent all King Henry’s gold.”

Robert shook his head.

“She is sixty thousand pounds in debt,” Cecil said quietly. “Sixty thousand pounds in debt, nothing to sell, nothing to offer against a loan, and no way to raise taxes. We shall find the money for her coronation but we will serve her best if we keep it cheap.”

Elizabeth’s triumphal procession from the Tower of London to Westminster Palace went just as Dudley had planned. She paused and smiled before the pageant representing her mother, the Lady Anne, she took the Bible offered her by a little girl and kissed it and held it to her breast. She drew rein at the points he had marked for her.

From the crowd came a small child with a posy of flowers. Elizabeth bent low in the saddle and took the posy, kissed the flowers and smiled at the cheers. Farther on she happened to hear two wounded soldiers call out her name, and she paused to thank them for their wishes and the crowd near them heard them predict that peace and prosperity would come to England now that Harry’s daughter was on the throne. A little later an old lady called out a blessing for her and Elizabeth miraculously heard the thin old voice above the cheers of the crowd, and pulled up her horse to acknowledge the good wishes.

They thought more of her for responding to the sailors, to the apprentice boys, to the old peasant from the Midlands, than for all the glory of her harness and the pace of her horse. When she stopped for the pregnant merchant’s wife and asked her to call the baby Henry if it was a boy, they cheered her till she pretended to be deafened by applause. She kissed her hand to the wounded soldiers, noticed an old man turn his face aside to hide his tears, and she called out that she knew they were tears of joy.

She never asked Robert, neither then nor later, if these people had been paid to cry out her name or if they were doing it for love. For all that she had spent her life in the wings, Elizabeth belonged to the center of the stage. She did not really care whether the rest of them were players or groundlings. All she desired was their acclaim.

And she was enough of a Tudor to put on a good show. She had the knack of smiling at a crowd as if each and every one had her attention, and the individuals who cried out to her—placed so that all corners of the route would have their own special experience of her—made a succession of apparently natural stopping places for Elizabeth’s procession, so that everyone could see her and everyone would have their own private memory of the princess’s radiant smile on her most glorious day.

The next day, Sunday, was the day of her coronation, and Dudley had ruled that she would go to the Abbey high on a litter drawn by four white mules, so that she appeared to the crowd as if she were floating at shoulder height. Either side of the litter marched her gentlemen pensioners in crimson damask, before her went her trumpeters in scarlet, behind her walked Dudley himself, the first man in the procession, leading her white palfrey, and the crowd that cheered her gasped when they saw him: the richness of the jewels in his hat, his dark, saturnine, handsome face, and the high-bred, high-stepping horse that curvetted so prettily with his hand steady on the bridle.

He smiled, turning his head this way and that, his heavy-lidded eyes running over the crowd, continually alert. This was a man who had ridden before a cheering crowd and known that they adored him; and had later marched to the Tower amid a storm of booing, knowing himself to be the second worst-hated man in England, and the son of the worst. He knew that this crowd could be courted as sweetly as a willing girl one day, and yet turn as spiteful as a neglected woman the next.

Today, they adored him; he was Elizabeth’s favorite, he was the most handsome man in England. He had been their bonny darling when a boy; he had gone into the Tower as a traitor and come out again as a hero. He was a survivor like her; he was a survivor like them.

It was a perfect procession and a perfect service. Elizabeth took the crown on her head, the oil on her forehead, and the orb and scepter of England into her hand. The Bishop of Carlisle officiated in the pleasing conviction that within a few months he would be celebrating her marriage to the most devout Catholic king in the whole of Christendom. And after the coronation service the queen’s own chaplain celebrated Mass without uplifting the Host.

Elizabeth came out of the dark Abbey into a blaze of light and heard the roar of the crowd welcome her. She walked through the people so that they could all see her—this was a queen who would pander to anyone, their love for her was a balm for the years of neglect.

At her coronation dinner her voice was lost in her tightening throat, the blush in her cheeks was from a rising fever, but nothing would have made her leave early. The queen’s champion rode into the hall and challenged all comers and the new queen smiled on him, smiled on Robert Dudley, the most loyal ex-traitor of them all, smiled on her new council—half of them constitutionally unfaithful—and smiled on her family who were suddenly recollecting the bonds and obligations of kinship now that their niece was no longer a suspect criminal, but the very lawmaker herself.

She stayed up till three in the morning until the trusted Kat Ashley, presuming on the intimacy of having been governess when Elizabeth was a girl and not a great queen, whispered in her ear that she must go to bed now or be dead on her feet in the morning.

God strike her dead on her feet in the morning, thought Amy Dudley, sleepless, waiting through the long, dark winter night for the cold dawn, in far-away Norfolk.

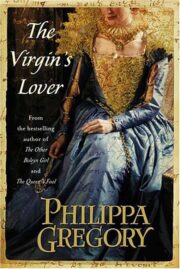

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.