She must return to London, to the society where she belonged. The thought of her returning to the sort of life she had led when he first saw her filled the Earl of Rutherford with dread. Women ordering her around, treating her like dirt beneath their feet. Children treating her with as much insolence as they knew their parents wopld let them get away with. Men eyeing her with lust, scheming how to coax her into their beds. She would be fortunate indeed if she found her way into a house where she would be treated with the proper respect. And even then it would be no life for Jess. His beautiful Jess.

Perhaps she had not heard or had not believed his assurances of the night before that he was going away, that he would trouble her no more. Perhaps it was her fear of him as much as anything that was driving her away. He must repeat his assurances to her. He must convince her that he meant what he had said. She must know that she could return to London and begin her social life again without the constant fear that she would meet him at every turn. She must feel entirely free to encourage other suitors and choose an eligible husband from among them.

Rutherford felt physically sick at the thought, but he resolutely put his feelings from him. He had renounced Jess the previous day. He must train himself now always to think of her as quite beyond his reach. It must be her happiness, and only hers, that occupied him for the rest of this day's business. As soon as he found her, he would take her back to Hendon Park, or to Berkeley Square if she preferred, and then leave, never to see her again.

He decided not to stop in London. His grandmother had assured him that Jess would already have set out on her journey north even before he left Hendon Park. It would be an utter waste of time to go to Berkeley Square on the slim chance that she would still be there. After all, if she was bent on running away from her grandfather, she was not likely to spend a few hours relaxing at his grandmother's house.

He would save time, he decided, by taking immediately to the northern road. His grandmother's crested carriage was easily recognizable. He would overtake it within the hour, if he were lucky, or certainly not too much longer than that. He would be able to bring Jess back before the middle of the afternoon.

It was only as one hour turned into two that Lord Rutherford regretted not returning home for his curricle. It would have been a slightly more comfortable mode of travel. He had not realized that the carriage could have had such a start on him. Jess must have made almost no stop at all at Berkeley Square. It made sense, he supposed when he thought about it. He would wager that she would not take with her any of the finery that his grandmother had provided her with. Packing her belongings would not have taken her long.

As the afternoon wore on, he became downright uneasy. Could the carriage have possibly come this far? Was there any chance that he had passed it? But no, that was impossible. It was equally impossible that it could have taken a different route. Lord Rutherford began to come to the unwelcome conclusion that the carriage must still have been in London when he passed the city by and that it was somewhere on the road behind him.

But did he dare take a gamble and turn back? If by some chance she was still ahead of him and he went back now, he would never catch up to her.

He rode onward for another five miles before deciding that he must turn back. As it was, it seemed unlikely that he would get back to London that night. And the weather was turning bitterly cold. He had been trying to ignore it all afternoon, but his hands were numb even inside his gloves, and the heavy capes of his greatcoat were failing to keep out the cold. Stray flakes of snow were beginning to drift down from a leaden sky.

Lord Rutherford did not afterward know what inspired thought led him to consider that perhaps his grandmother's carriage was not on the road at all. Was it certain that that was how Jess was traveling? His grandmother had said so, of course. She had offered the carriage. But was it really certain that Jess would have accepted? Was it not far more consistent with her stubborn character and with her determination to return to her former life, for her to have decided to travel by. the stagecoach? He had passed several since leaving London. She could have been on any one of them!

And so he made his way back, uneasy about his decision to do so, cold, worried about his tired horse, and determined to examine every stagecoach he passed to make sure that she was not on any of them. Soon, of course, most of them would stop for the night. He must look carefully at each inn to see if a stagecoach stood in its yard.

He hailed two stagecoaches on the road without success before spotting the one in an inn yard. Snow was falling. It was almost dark. He felt hopeless. He had lost her. Somehow he had missed her, and he would never see her again. He would never be able to explain to her that she was making an unnecessary sacrifice of her life.

He asked for her by name, slipping the innkeeper a large coin as he did so. It was amazing to be told that yes, she was upstairs in the attic room. After the long journey of the day and all its worries and uncertainties, it seemed almost too easy to find that she was here, at the very first inn he checked.

There was no spare room at the inn. Rutherford placed another coin in the innkeeper's hand and began to climb the stairs to the attic.

16

Jessica stiffened when the knock sounded on her door. She might have known that her good fortune was too good to be true. She was going to have to share her room after all. The bed was certainly large enough to accommodate more than one person.

"Yes?" she called out hesitantly, wishing that she could pretend to be deaf.

There was no answer for a moment. Then her blood ran cold.

"Jess?" a familiar voice said.

Jessica leapt to her feet. Her book slid with a thud to the floor and her cloak slipped from her shoulders. "Who is it?" she called foolishly. There was only one person in the world it could possibly be. "What do you want?"

"May I talk to you for a minute?" the Earl of Rutherford asked.

"What about?" she said. "What do you want? I have nothing to say to you."

"Jess." He was speaking quietly through the thin door. "Will you please open the door? I have something of great importance that I must say to you. I give you my word of honor as a gentleman that I will not touch you."

"Go away," she said. Her voice was shaking, she noticed in some alarm. "Please go away."

"Jess, please listen to me," he said. "Please open the door. The innkeeper will be up here soon wanting to know what all the commotion is about. Just listen to me. Hear me out. Please."

She pulled the door open and immediately felt what a tactical error it was to have done so. He looked huge, clad still in his greatcoat and topboots. His hat and whip were in his hands. His hair was disheveled, his face rosy with cold. He looked impossibly handsome.

"My lord," she said breathlessly, "I do not know how you have found me here. But I will not be harassed any longer. I have left your father's house and your grandmother's. I am on my way to a new situation. I want nothing more to do with you. I thought I had made that plain. And I seem to recall that you promised just last night that you would leave me alone. Please go away."

"Jess," he said, "let me in. Let us not entertain a whole inn with our quarrel. No, you are quite safe." He said this as he stepped inside, closed the door behind him, and threw his hat and whip onto the bed. "I have promised not to touch you."

Jessica watched him warily and backed between the wall and the bed down toward the washstand.

"You must come back," he said. "This flight into Yorkshire and return to a life of service is madness, Jess. And totally unnecessary. You do not belong in such a life."

"Your tune has changed drastically within a few weeks," Jessica said. She was beginning to feel more in command of herself. "Until you discovered my grandfather, this was exactly the life in which I belonged."

"No," he said. "You forget that I offered you a very different life even before I discovered that you are Heddingly's granddaughter."

"My life is none of your concern anyway, my lord," she said. "If I choose to take a situation as a governess, that is my business only. I do not owe you an explanation."

"No, you do not," he agreed. "You owe me nothing,

Jess. Nothing at all. It is not for myself I plead. It is for you. I do not believe that you can be happy with such a life. And I have reason to believe that you are returning to it because of what I have said to you. But it is not true, Jess. It is not true that your reputation is ruined. You do not have to flee from society."

She looked at him, amazed. "Flee from society?" she said. "How absurd! Do you think I care what other people say of me?"

"Yes, I think you do," he said gently. "But other people are saying nothing, Jess. I made the situation sound very bleak yesterday morning, did I not, when I was trying to persuade you to accept my offer. I wished you to believe that you had no choice, that marriage to me was your only way of avoiding great scandal. But it is not so at all. I lied."

"Why?" she asked. She had moved around to the foot of the bed and held on to one of the bedposts.

He shrugged and smiled somewhat apologetically. "I don't know," he said. "I suppose I considered it a sure way of getting you to agree. Not very honorable, was it? And foolish, as it turned out."

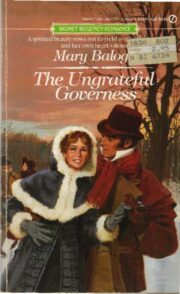

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.