"Oh dear," she said. "I really should not have looked up. I thought I was doing quite well until I did."

Lord Bradley laughed. "It is a humbling experience, is it not," he said, "to find that one performs some skill less well than even the smallest child? I would not worry about it, Miss Moore. You will do well with practice. You are relaxed. Many people tense up as soon as they step on ice. Then of course when they fall, which they inevitably do, they fall very heavily. I hate even to remember some of the bruises I sported during the first winter of my marriage to Faith."

Jessica laughed.

"Let us try an experiment," he said. "Link one of your arms firmly through mine. Right. That will do. Now let us see if you can skate along with me. Quite sedately, ma'am, as if we were strolling through Hyde Park on a spring afternoon. I shall not let you fall."

And without the total support of one of his strong arms beneath each of hers, Jessica found that the thing was still possible. When her skates did suddenly move too fast and threatened to leave the rest of her behind, the arm through which her own was linked tightened with reassuring firmness and she regained her balance with only a slight loss of dignity.

"How well you are doing, my dear Miss Moore," the cheerful voice of Lady Hope called as she and Sir Oodfrey came skating effortlessly up to them. Her cheeks beneath the fur-lined hood of her blue cape were glowing brighter than ever. A few strands of dark hair had blown loose about her face.

"I am afraid I owe all my prowess to the steadiness of Lord Bradley," Jessica said ruefully.

"I am quite sure you would do equally well with a little support from any partner," Lady Hope said. "All you need is confidence, my dear. Sir Godfrey, I am sure you would enjoy taking a turn about the ice with Miss Moore. Do so, please. Do not mind me. I have promised to play with the children."

"And I have just been congratulating myself on capturing the best skater on the ice for my partner," Sir Godfrey said, relinquishing her hand. "You are quite wasted on the children, ma'am."

"Oh, is not that a foolish thing?" she said. "Your flattery is quite outrageous, sir. What would you want with twirling about the ice with someone like me? Aubrey, if we can arrange the children in two long lines, each clasping the waist of the one in front, we could have a very enjoyable race-you at the head of one line and me at the head of the other."

Lord Bradley groaned. "Try Charles with your mad schemes, Hope, please," he said. "I intend persuading Faith to skate sedately around the perimeter with me, as befits a couple approaching middle age. She thinks she is of an age to retire from skating altogether, of course. I intend to disabuse her."

Jessica found her arm being transferred very carefully to Sir Godfrey's.

"Come then, Miss Moore," he said, smiling cheerfully down at her. "Lady Hope thinks she has very subtly thrown us together in company again. She will eventually be most disappointed, will she not, when she discovers that we do not have a tendre for each other at all?"

Jessica skated gingerly at his side. He was not nearly as large and solid as Lord Bradley. "You mean you do not?" she asked. "I am shattered, sir."

"No, you are not," he said. "I believe Miss Jessica Moore has eyes for only one gentleman, and he, alas, is not I. Perhaps it is just as well that my feelings too are otherwise engaged."

Jessica looked up at him quite startled, completely forgetting that every jot of her attention needed to be focused on her skating. One foot shot out from under her, she turned to try to grasp her partner's arm with her free hand, her feet became hopelessly tangled up with each other, and somehow she found herself sprawled ignominiously face-down on the ice.

Pain was lost for the moment in embarrassment. Some female close to her shrieked. Several children laughed. Sir Godfrey apologized.

"My dear Miss Moore," he was saying. "Are you hurt, ma'am? How could I have let you fall like that? I am most dreadfully sorry."

Jessica pushed herself to her knees and brushed ineffectually at the snow that clung to her cloak. "I am all right," she said in a daze. "How foolish of me."

She took a firm grasp of the arm held out to her and pulled herself somehow to her feet with its help. She clung with both hands.

"Oh, thank you," she said, looking up into the rather amused face of the Earl of Rutherford.

"Oh, but you have hurt yourself," he said, the amusement fading. He pulled his glove off his free hand with his teeth, reached into a pocket for a handkerchief, and stuffed in the glove in its place. "You have cut your mouth."

She was totally his captive. The death grip she had on one of his arms was the only thing that ensured her survival, she was sure. Several people skated up to them to exclaim and commiserate. Sir Godfrey hovered, delivering abject apologies until Lord Rutherford sent him off to deputize for him in Lady Hope's race. He dabbed the handkerchief gently against Jessica's lips. She was shocked to see it come away red. Her mouth was only just beginning to throb.

"Come," he said, "we will go and sit on the bench for a while. No, don't look so terrified." The amusement was back in his eyes for a moment. "I promise you will not fall again. I shall pick you up and carry you if you wish, but it would be a most ignoble end to an heroic first skating lesson, do you not think?"

They were seated on the rickety bench a minute later, Lord Rutherford again turning his attention and his handkerchief to Jessica's mouth. She reached for the handkerchief in some embarrassment, but he tightened his grip on it.

"There is no mirror here," he said. "Let me do it. What did you do, do you remember? Did you bang your lip on the ice or bite it as you fell? A foolish question. You are quite incapable of answering at the moment. Let me see."

He took the handkerchief away and she felt a gentle thumb at either side of her mouth pulling down her lower lip.

"It is not as bad as it could be," he said. "You have not bitten the inside of your mouth. You may have a fat lip for a day or so, Jess, but I do believe you will be able to enjoy your Christmas dinner tomorrow."

His eyes were on her mouth. Uncomfortable feelings were churning Jessica's insides, completely distracting her mind from the throbbing lip. She felt no better at all when he looked up into her eyes and grinned.

"Do you have any other injuries?" he asked. "Two scraped knees, for example?"

"No!" Jessica said very firmly. "I am quite all right, I do assure you, my lord. This is all very humiliating."

"And certainly not the memory to leave with the whole houseful of guests," he agreed. "Come. You will skate with me."

"No," she said sharply. "No, I think I have entertained everyone quite sufficiently for one day, my lord. I shall go back to the house. I wish to talk to my grandfather."

"If you leave now, Jess," he said, "you will never find the courage to return to the ice, you know."

"I do not feel I shall consider the lack the great tragedy of my life," she said.

"Coward!" he accused, grinning. "You were doing quite nicely with Aubrey. Godfrey, of course, is a careless creature who probably became so absorbed in conversation that he forgot he was your sole prop and staff. Trust me. I will not let you fall."

It was the charge of cowardice that did it, probably. Jessica rose to the challenge even as she realized that the word had been deliberately thrown out to goad her. She got to her feet and wobbled slightly even before he jumped up and drew one arm firmly through his.

"Try this," he said when he had lifted her down to the ice. A few lone skaters were twirling around. The main bulk of children and some of the adults were in a dense and noisy group at the far end of the ice, the race presumably over. "We will pretend we are waltzing. You may put your hand firmly on my shoulder. Grasp one of my capes if you will feel safer. Your other hand quite firmly in mine. And my other hand at your waist like this. Now, have you ever felt safer in your life?"

Many, many times, Jessica thought, her face upturned to his, drowning in his eyes. Oh yes, at almost any other moment of her life that anyone would care to name she had felt considerably safer than she did at this moment.

"One problem," he said. "We cannot possibly waltz without music, can we? I would hum a tune, Jess, but I am afraid you would not even recognize my efforts as music. You will have to do it."

"Hum a tune?" she asked, incredulous.

"A waltz tune," he said. "Any one, Jess. Anything that goes one, two, three, one, two, three."

"How foolish!" she said, glad of her cold-reddened cheeks that must mask the blush she could feel hiding beneath.

"Coward, Jess?" he asked with one eyebrow raised, and she found herself humming a waltz tune that she remembered from Lord Chalmers's ball.

"Mm, lovely," he said, smiling down at her and skating slowly backward in time to the music, drawing her with him. "But we will have to make one adjustment for your safety. Clasp both hands around my neck, Jess, and I shall set one on either side of your waist. Ah, much better, is it not? The music again, please, ma'am."

She wanted to cry. How very stupid to want to cry. She felt so safe. It w:as her hold of him and his of her that kept her on her feet, of course, but she felt light, as if she skimmed over the ice of her own volition. They moved very slowly, but the hissing of their skates on the ice gave an impression of speed. His eyes held hers as she hummed her tune almost without realizing that she still did so. For the space of perhaps two minutes nothing and no one existed outside the circle of their arms.

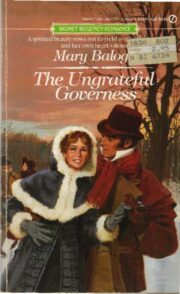

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.