But she had known when she was forced to look at him at last. The dowager had told her that it was Lord Rutherford who had brought her grandfather, and she had been forced to look at him and acknowledge the fact. He had been standing there before the fire exactly as he had when she had entered, the same stony expression on his face. There was no sign of gladness for her happiness, no sign that he had done what he had done for her sake. He had barely acknowledged her thanks.

She had wanted to jump up at the dowager's words, throw her arms around him, and share her joy with him. But he had looked like a man made of stone. And all day he had ignored her. He had talked with almost everyone else in the house, had appeared progressively more cheerful as the day wore on, had talked with and teased the children, whose favorite he clearly was as much as Lady Hope was. But she might have been a hundred miles away.

How perverse of her to have expected or even wanted some sign from him, she thought. What did she expect? That he still wanted her? She had convinced herself and told him in no uncertain terms that she had no interest in being wanted merely. Did she expect that he would treat her with more respect, deeper regard, knowing who she really was? She would despise such a change in his behavior.

So what did she want?

Jessica turned her head to rest her cheek on her knees. She wanted his love. How very, very foolish! What had she ever done to earn the love of the Earl of Rutherford? And what had he ever done to make her crave his love? He was a man for whom the satisfaction of physical appetites was the most important thing in life. A man to despise.

Or was he? He had respected her wishes on more than one occasion, although she knew that on one of those occasions she had asked more of his self-control than any woman had a right to ask of a man. He had charm and knew how to set one at ease in conversation. There was some kindness in him. How many gentlemen would give up their bed to a mere governess? Especially when that governess did have a bed of sorts to go to? And he was dearly loved by a family of which Jessica was growing increasingly fond. There must be good in him when she had seen how anxious all his family had been lest he not appear for Christmas.

It was stupid to pretend. Of course she felt a strong physical attraction to Lord Rutherford. She would be almost unnatural not to do so. He was extraordinarily handsome, and she had moreover tasted his kisses and caresses. Yes, of course she wished to be in his bed again but without any of the moral scruples this time to prevent her from knowing the deepest caress of all. Of course she wanted all that. Her body ached and throbbed at that very moment for his touch.

But it was not just that. Oh, of course it was not just that. She wanted Lord Rutherford. All of him. Every-thing that made him the person he was. She wanted him to talk and talk to her, as he had at dinner at the inn. She wanted to share her thoughts and emotions with him as she had done unconsciously at Astley's. She wanted to laugh and be teased by him, as his nephews and nieces and cousins had been that day. She wanted to know him.

Could one love someone one did not really know very well at all? If not, what other name could she use to describe this feeling that was washing over her, that would not let her go? This feeling she had not been free of since that night at the inn?

And how foolish to love a man whose offer of protection she had refused twice, and whose marriage proposal she had rejected with some contempt. How very foolish to be depressed because he had shown no interest in her for a whole day. How ridiculous to have felt in the drawing room earlier in the evening that half the candles must have been snuffed merely because he had left the room talking and laughing with a couple of his cousins.

She must live out the week somehow, Jessica decided. And then she must studiously avoid him whatever Grandpapa's decision was about where they would live. She must put him out of her mind, out of her life. She must encourage one of her present suitors. Or allow Grandpapa to find her an eligible husband.

That was what she would do. She would concentrate on being a docile and obedient granddaughter. Had she done so two years before, she would probably be contentedly married by now and even perhaps have a baby of her own. She would have been immune to these painful and dreadful excesses of emotion.

What was he doing now? she wondered as she slid down in the bed to lie staring at the canopy over her head, picked out by the flickering of the flames in the hearth. Was he asleep? Had he spared even a single thought for her? Did he still find her desirable?

Jessica closed her eyes. Enough! she scolded herself. Tomorrow perhaps she would be able to have some private time with Grandpapa, and she would find out what was to be arranged for her future.

12

To the delight of all members of the younger generation, and some of the adults too, the ice on the large pond north of the house was declared solid enough for skating the following morning. By luncheon time a contingent of servants had cleared the snow off the surface, and the ice was smooth and clear, shining invitingly in the watery sunlight. The same servants carried out two large boxes of skates of all sizes that had accumulated over the years.

"We all skate almost as well as we walk and ride," Lady Bradley explained to Jessica as they walked side by side out to the pond. They were slightly behind the main party of exuberant children, and adults trying to appear more dignified. "Hope and Charles and I, of course, had numerous opportunities as children to skate here. And even our cousins have been fortunate. If the weather is not cold enough at Christmas, Mama usually invites them all out here again in January. Of course, it is always a disappointment if there is no snow or ice at Christmas."

"I have tried skating only once, I am afraid," Jessica said. "It was on the village pond when I was quite a child. I seem to remember spending more time sliding around on my posterior than impressing the villagers on my skates. They were very much too large for me as I recall."

Lady Bradley laughed. "That was probably the whole problem," she said. "It is essential to have the right size skates laced to your boots so that they feel almost part of your feet. But you really "must not be too shy to try today. There will be plenty of skaters willing to help you along until you get your balance."

Jessica felt even more dubious when they arrived at the pond to find that several of the children were already dashing all over the surface of the ice as if moving on blades at high speed were the most natural way in the world to move around.

Lady Hope was looking brightly animated, seated on a makeshift bench, strapping skates to her boots and trying at the same time to help the efforts of two small children. Her cheeks were already flushed from the brisk air.

"Ah, you have decided to try after all, Miss Moore," she called. "I was sure your refusal at breakfast time was mere temporary cowardice. You will find it easy once you try, I do assure you. Penelope and Rupert both learned to skate last year, but they have convinced themselves that they no longer know how. I am going to show them how wrong they are. Come on, children."

She took a child's hand in each of her own, helped them down from the bank onto the surface of the ice, and skated slowly across its surface, encouraging the wobbly-legged younsters with a continuous and cheerful monologue.

"Here," Lady Bradley said, returning to where Jessica stood. She had one arm linked through her husband's. "Aubrey has volunteered to be your instructor, Miss Moore. I do assure you that he is as solid as a rock on the ice and will not let you fall."

"I think perhaps for this afternoon I shall watch," Jessica said.

"Nonsense, Miss Moore!" Lord Bradley immediately stooped over one of the boxes of skates and drew out a likely pair, his eyes moving critically from the skates to Jessica's feet. "Try these. You will be considered a poor creature indeed among this family if you cannot skate. I know. It was one of the first things I had to learn when I married Faith. There is nothing to it really once you have sensed the correct balance over your skates."

Jessica was far from convinced as he stooped in front of her and began to strap the skates to her boots. She was about to make a dreadful cake of herself. The children would surely consider the show more entertaining than the clowns at Astley's. And the adults! How foolish she would appear. Lord Rutherford was out there, skating very expertly with a young female cousin of his, even twirling with her and skating backward as well as forward.

"Well," she said, smiling bleakly up at her teacher after he had strapped on his own skates, "I do hope you are as rocklike as Lady Bradley claims, my lord."

He was a very solid and dignified man, one whom she had rarely seen smile or heard speak a frivolous word. But as she took his hand and allowed him to help her to her feet, she was very glad of that solidity. Even before he stepped down onto the ice and helped her after, she felt as if her ankles would not be able to cope with balancing her weight above the flimsy blades.

But really, she discovered after a couple of minutes during which her eyes did not leave her boots, the thing was perhaps possible after all. It was true that Lord Bradley was probably supporting every last ounce of her weight, but she was beginning to feel some exhilaration. She was actually skating! She dared to look up for a moment at all the twirling figures, huddled warm inside their fur-lined cloaks and hoods, scarves covering necks and mouths.

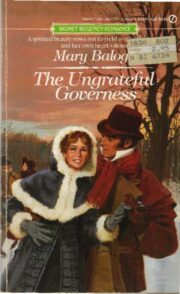

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.