“She knows about you … about all of it?”

He shrugged. “A man can’t be a stranger to everyone. Someone’s got to know who you are.” Seeing as I’d declined the brandy, he drank it down. “Besides, she helped me. She was a doxy in one of those rat-hovels on Bankside, growing long in the tooth; her customers weren’t getting any younger, either. She found me washed on the shore that night I escaped the Tower, my legs all smashed up and my face-well, you can see what they did to my face. She and the other whores in the neighborhood fetched me indoors and tended to me. It took weeks before I could open my eyes or uttered a sound, Nan said. Had it not for that pack of cunnies, I’d have died.”

“And now you two live together?”

“You could say that. After I healed-or healed as much as I ever would-I hired myself out as a strongman for the brothels; Nan and I tucked away every coin we earned. In time, we saved enough to buy this place from an uncle of hers, a drunken lout who barely kept it running. He died on that settle, from liver rot. Miserable bastard he was, but he did Nan a decent turn in the end. At least now, she needn’t sell herself for bread.”

My head reeled, as much from the aftereffects of my recent imbroglio as from the very idea that Archie Shelton, previously steward to the noble Dudley household, now ran a tavern with a former whore.

“Surprised?” His one eye gleamed. “I must admit, I was, too, at first. Didn’t think I’d stay long. But I like it here. I’m thinking of taking up permanent residence and working full-time. After that ugly bit of trouble with the earl, I figure it’s time for old Scarcliff to retire.”

My throat tightened with emotion. “That’s twice now you’ve saved my life.”

“Yes, it is, isn’t it? You certainly have a penchant for getting into trouble.” He went silent for a spell, staring into the crackling hearth. “Did you do it?” he said at length. “Did you help her?”

I sighed. “She’s going to the Tower, but I have assurance she’ll not be killed.”

Though his ravaged face could barely register an expression, I could tell he was incredulous. “Assurance from whom? The queen?” He snorted. “I’d not put much trust in her if I were you. Not if you’ve seen the dead hanging on every corner and those fresh heads on the bridge. She went to the Guildhall when Wyatt’s men were spotted across the river; she swore up and down she’d never marry without her people’s consent. She got the city all riled up so they’d march to her defense, like they did that time before, against the duke. But she lied. She’ll marry the Hapsburg. Wyatt had the right idea; he just went about it wrong.”

“I see your point,” I said. “But it’s not her word alone I’m counting on.” I drew the blanket closer around me. I was naked under it, the discarded ruins of my clothing sitting in a dripping basket by the fire. The smell of herbs wafted from my shoulder; Nan must have tended the wound. It hurt, though it probably felt worse than it was.

“Do you want to tell me what happened?” he asked.

I didn’t. I didn’t want to relive it, not yet. I found myself telling him anyway, my voice remarkably calm as I related what had occurred, everything but what I’d confided to Mary about my secret. When I finished, he sat with his lower lip protruding, as though he were ruminating on a particularly vexing issue. “Are you sure it was her? It’s a long fall off the bridge.”

I considered. “It was very dark in the tunnel. I didn’t see her.”

“Then maybe it was your imagination. Maybe Renard found out you’d snuck into the palace to see the queen and sent someone after you. Or perhaps Rochester told him. It’s the court, lad. Nothing is more important to a courtier than his own hide, and you’ve a lot of secrets to spill.”

“Maybe,” I conceded, reluctantly. “But that scent: Only she wore it. And it was everywhere. As if she’d doused herself in it, because she wanted me to know she was alive.”

He looked doubtful. “In all that muck and mire, you could smell her?” He grunted. “I suppose it’s possible. Hell, anything’s possible. But if she survived that fall without breaking her neck, she’s more experienced than anyone I’ve known. The way she handled her sword, and now this: She’s had training. I’ve never heard of anyone jumping off the bridge in the middle of winter and living to tell the tale.”

I had to agree. Sitting in his cramped parlor above the Griffin, after having nearly drowned in a sewer, I had to doubt my own experience. The tunnel had been suffocating, a nightmarish labyrinth. I must have lost my reason. It seemed utterly improbable that Sybilla could have plunged into the Thames and not died instantly. Mary had told me she had paid the price, but I had not thought to ask if her body had been recovered. I was glad I hadn’t. It was better if I never knew. I had to believe she was dead. I didn’t want to consider what I would do if I found out otherwise. The hunt for her would destroy my existence.

“I must be at the Tower tomorrow,” I said at length. “I have to see it.”

He turned to the door as Nan came trudging back up the stairs.

“Then we will,” he said.

* * *

The next morning, he located old garb for me that had belonged to the dead uncle: a shirt, an itchy doublet that smelled faintly of lavender and more strongly of mold, mended hose, an oversized cap that flapped about my ears, and shoes too big for my feet. The dead uncle had been larger than me, I thought absently as I dressed, glancing at my contused arms, the purpling bruises on my torso, and the aching shoulder wound wrapped in a bandage; that, and I had lost too much weight. Shelton unearthed a worn belt from the clothes press to keep everything more or less in place. My other clothes were ruined. Nan had painstakingly tried to salvage them, but the taint of sewage was ineradicable, and I told her to give up. My boots could be salvaged, with care and loads of fat rubbed into the leather to restore its pliancy, after they dried out. I was most concerned for my sword, but while I slept Shelton had wiped away the moisture and filth and polished it to a bright hue.

We set out to an early morning that felt like spring, the sun breaking through the clouds in brilliant shafts that soaked into the frigid land. As we walked toward the Tower wharf on the west side of the fortress, I heard chirping in a beech tree and looked up, startled. A robin sat on bare twined limbs, where tiny buds were already visible-a welcome reminder that even this winter must pass, although it was hard to think that spring would find Elizabeth, Kate, and Mistresses Ashley and Parry behind prison walls.

It was a small crowd, not at all what I’d expect when a princess is sent into captivity. Today was Palm Sunday, Shelton told me, to my surprise, and official proclamations from the palace plastered on every wall encouraged the city’s denizens to attend worship in the old tradition.

“Must be deliberate,” Shelton said in my ear. “They don’t want too many to see her going into the same place where her mother died. The people love her. They’re starting to realize she truly is their last hope.”

I stood with him among the handful who’d gathered on the side of the Tower entrance, the roars of the caged lions in the menagerie seeming to herald Elizabeth’s arrival. At first, I thought she’d be brought by barge into the Tower via a water gate, but Shelton reminded me the tide ran too low at this early hour. They’d bring her to the wharf, as close as they could get, but she’d have to walk inside on her own two feet.

So it was that, hidden among curious onlookers, I saw her disembark from her barge and stand, utterly still, a hand at her brow as she gazed up at the looming bastion. She wore a black cloak, the hood drawn over her head, but as the guards cordoning the walkway shifted more tightly together and an audible murmur rose from the spectators, she cast back the hood to show her face.

She was very pale, yet appeared outwardly composed, escorted by five somber lords toward the same gateway through which I’d entered the Tower. Close behind her were Mistresses Parry and Ashley, holding bags stuffed with belongings, and a well-formed yeoman in the Tudor livery, carrying the traveling chest filled with her treasured books. My heart wrenched when Kate hastened from the barge to the princess’s side, the last to disembark; as she joined Elizabeth, her hand dropped surreptitiously to clutch the princess’s. Elizabeth turned nervously to her, as if Kate had murmured words of encouragement, and then redirected her gaze outward to the watching crowd.

“God keep Your Grace!” shouted a goodwife. As her shrill encouragement faded into the morning air, others lifted chorus, as if they’d been rehearsed: a fervent cry of good wishes that brought Elizabeth to a standstill. The lords, among whom I espied the tall, white-bearded figure of Lord Howard, exchanged concerned looks. Did they actually fear an impromptu rescue?

Elizabeth was looking directly at us, her eyes like black punctures in her pinched face; she could not acknowledge the greeting. Under suspicion of treason, about to enter the very place from which few ever emerged, she mustn’t risk the accusation that she’d incited the mob. Yet even from a distance I could see how those cries moved her, how she gazed at us with heartrending intensity, as if she sought to engrave this sight in her memory as a talisman to carry with her during the ordeal yet to come. Her fear ebbed away; in its place, for the briefest of moments, like a glimpse of spring on a bare tree, she showed the strength that made her undeniably a Tudor.

I started to push forward, elbowing those around me. The people in front of me grumbled. Shelton chopped his hands at them; they took one look at his mutilated face and quickly shifted aside. All of a sudden, I found myself pressed against the barricade, peering past the row of guards. Howard had urged the princess forward. She took a step away from him, resisting. I yanked off my cap, heedless of the consequences, waving it as high above my head as I could. Everyone around me followed suit, whipping off their headgear-a flotilla of caps and veils and bonnets, swaying in the air like crude flags.

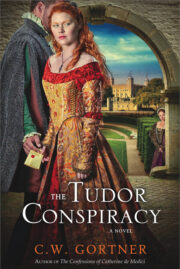

"The Tudor Conspiracy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Tudor Conspiracy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Tudor Conspiracy" друзьям в соцсетях.