* * *

I reached Ashridge by nightfall.

Newly fallen snow draped over the Hertfordshire countryside. As I clattered into the courtyard, a groom came running out to assist me. I unhooked my saddlebag and dragged myself into the manor.

Mistress Parry greeted me from the torch-lit hall with a frightened gasp. “Sweet mercy, look at you!” Only then did I realize how I must present, covered in mud and mire from the road and crawling through gaps in stone walls and tunnels; my cloak bedraggled, my tunic torn, my arm blood-caked and my entire person stinking of sweat and horse.

“It’s been a long day,” I said, removing the cylinder with Elizabeth’s letter and divesting myself of cloak and scabbard. She took them from me. “Where is Her Grace?”

“She’s gone to her chamber to rest.” Mistress Parry’s voice quavered as she eyed the cylinder in my hand. “What is the news from London? Is she … are we still in danger?”

“I fear so. I’ve done all I can. But we should prepare; it is likely the queen will send men to question her. I must talk with her first.”

She clutched my belongings as I turned to the staircase. “Should I send to Hatfield for Mistress Ashley and Mistress Stafford?” she suddenly asked.

I froze. Then I nodded. “Yes,” I said, “I think you should.” I continued up the stairs.

When Kate arrived, I would tell her everything.

* * *

The princess’s bedchamber door was ajar; I knocked to announce my presence and entered. The room was small, wainscoted in linen-fold paneling and warmed by a fire burning in a recessed hearth. Strewn about were her open coffers and traveling chests. From what I could see, she’d unpacked her books and a few scattered articles of clothing.

She looked up. She was sitting on the edge of her bed, a lit candle by her side, an open book in her lap. Her hair hung loose over her shoulders, a red-gold sheen blending with the scarlet of her robe. She looked so young, so vulnerable, without the accoutrements of her court regalia: a mere girl. Not a princess at all.

A knot filled my throat.

I extended the cylinder I’d carried close to my heart the entire ride.

“You are a man of your word,” she said. She set it unopened on the table next to her candle. “Is it done?”

“No. But there is no evidence against you.”

She did not reach for the cylinder, did not react in any way as though she were interested in its contents, as I relayed what I had found out, about Sybilla and Philip of Spain and their plot to hold her hostage to the prince. She did not interrupt or ask a single question. She sat so still when I was done that she might have turned to stone, had it not been for the rapid rise and fall of her breast.

“I had no idea he considered me such a prize,” she said at length. “I find cold comfort, considering it’ll be yet another reason for Mary to despise me.”

“She doesn’t know-” I began, and the room keeled around me. My knees gave way; I almost fell as I reached for the nearest chair.

“You are wounded,” said Elizabeth. “You must sit.”

As I sank onto the chair, weak as a newborn foal, she went to one of her chests and extracted a painted casket. She pointed at my arm. “Let me see.”

I shook my head. “It’s nothing. There is no need-”

“Don’t argue. Take off your doublet and shirt and let me see. If it festers, Kate will never let me hear the end of it.” She opened the casket as I reluctantly shed my upper clothing. When I looked at her, she had set out a jar of salve and folded linen cloths. Taking up the pitcher of water from her sideboard, she bent over me and cleaned my wound. With the crust and dried blood washed away, I saw it was deep but not large.

Her fingertips felt cool as she probed the ragged skin. I winced.

“You’re like a bear after a baiting,” she said. “Stay still. This might sting. It is Kate’s special salve; she made a batch for me before I left Hatfield. I always carry it with me.”

Taken aback by her determination, I let her salve the wound with the rosemary and mint concoction, releasing the very aroma of Kate into the air. She worked efficiently, without revulsion. I’d forgotten that she had lived most of her life far from court, in a country setting where even princesses must learn rudimentary healing skills. The salve eased my pain, inducing a welcome numbness. I reached for my chemise immediately after, my breeches sagging perilously low on my hips.

“There. Better, yes?” She returned the items to the casket. “You should use the salve at least once a day, twice if you can manage it.” She scrutinized my face. “That other wound on your temple should be tended, too. No matter what most physicians say, even such minor hurts can gather dirt. If corruption sets in, you will sicken.”

She spoke matter-of-factly, as if I had not informed her that a revolt could at this very moment be upon London and that she was far from safe-indeed, that all of us were in danger.

“What are we going to do?” I finally asked.

“What can we do? We wait.” She paced to the side table, her long fingers hovering over the cylinder. “Whether Wyatt succeeds or fails; whether my sister chooses to believe in my guilt or innocence; whether I’m left alone or taken-only time can tell now.” She glanced at me. “Though if the situation is as dire as you say, I should think that we’ll have our answer sooner rather than later.”

She picked up the cylinder.

“What does that letter say?” Though I had told myself that I would not ask, I couldn’t stop myself. All of a sudden, I had to know exactly what I had sacrificed so much for.

She paused. Cylinder in hand, she moved past me to stand for a long moment before the hearth. She pulled back the grate; with a flick of her wrist, she tossed the cylinder into the fire. “I told you at court, you had one chance. Now, it is best if you do not know more than you already do. You’ve suffered enough for my sake.”

Her rebuke did not surprise me. It had been presumptuous to assume she’d deign to confidence now. Her words to Robert Dudley would remain a secret between them, the evidence even now curling to ash in her hearth.

“Will you eat?” she asked. “You must be famished.”

Holding on to the chair, I hauled myself to my feet. “No, I just want to sleep.”

“Go, then. Mistress Parry will see to your chamber. We’ve hardly a full house here; there are several rooms to choose from.” She remained at the hearth, the firelight limning her figure in a reddish glow. As I moved to the door, I felt her gaze follow me. My hand was on the latch when my question came out, unbidden. “Will you allow me one thing?”

She nodded. “If I can.”

“Was it worth it?”

She sighed. “I have found it’s always worth fighting for what we believe in, regardless of the outcome. Risk is never without consequence.”

I inclined my head.

“And you?” she asked. “Would you have fought for me as you did, had you known the entire truth?”

I hesitated for only a moment. “Yes,” I said. “No matter what you have done, I believe in your cause.”

She gave me a dry smile. “I’d expect nothing less. Rest, my friend. You’ve earned it.”

* * *

I feared that I might not be able to sleep, that the events of the past days would haunt me in the silence of unfamiliar quarters. In fact, as soon as I disrobed and climbed into the musty bed, I fell fast asleep, without dreams, for the first time since I had left Hatfield.

When I awoke, it was past midday. I could tell by the angle of light filtering through the window. Mistress Parry had sent someone up while I rested, who’d seen to my needs. Along with a fresh shirt, my breeches and hose were folded in a neat pile by my saddlebag, crinkled and stiff from having dried by a fire but blessedly clean and scented with lavender. After I washed and tended to my arm, I went to the hall. In the daylight, Ashridge was visibly as well appointed as the manor at Hatfield; it had the requisite furnishings and size, but the feel of disuse hung in the air, as in all places that are rarely inhabited.

I ate my fill, seated alone at a wide table, served by a blushing maid I didn’t recognize but assumed had been the one who attended to my clothes. I was told Elizabeth remained in her chamber, so I went out to check on Cinnabar. I found him well stalled, with a warm blanket to cover him, and plenty of feed. Urian nosed the straw around his hooves; as the hound recognized me, he let out a joyous bark. Tears sprang in my eyes when I recalled Peregrine’s love for this dog. I buried my face in Urian’s fur as he licked my hands, whining low in his throat as though he could sense my sorrow, and let myself grieve.

Then I wiped away my tears and took Urian into the snowy courtyard to toss a stick, delighting in his eager retrieval, his lopsided gait, and his barks for more. It had been so long since I’d done anything so ordinary, so normal-it felt odd and wonderful at the same time.

Finally he was panting, his tongue lolling, and my hands felt like frozen mutton. Turning back toward the house with Urian at my heels, wondering if the princess was awake yet, I discerned the clangor of hooves. Even as I turned toward the road, I knew what I would see: men in cloaks and caps, galloping toward the manor.

I bolted into the house. Our answer had come.

* * *

Mistress Parry had also heard the approaching party. She was halfway down the staircase, kneading her skirts. She took one look at me and said, “Her Grace says you must hide. No one can see you here. You might be recognized.”

“What of her?” Her anxiety was infectious; I found myself looking over my shoulder as I spoke, half-expecting the front door to burst open to reveal men at arms.

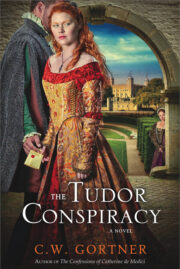

"The Tudor Conspiracy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Tudor Conspiracy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Tudor Conspiracy" друзьям в соцсетях.